'Keep quiet'

Confidential emails reveal a top Wells Fargo advisor’s despair after he cried fraud. He could stay at Wells if he was silent, but spoke up anyway — and became a whistleblower.

By Ann Marsh

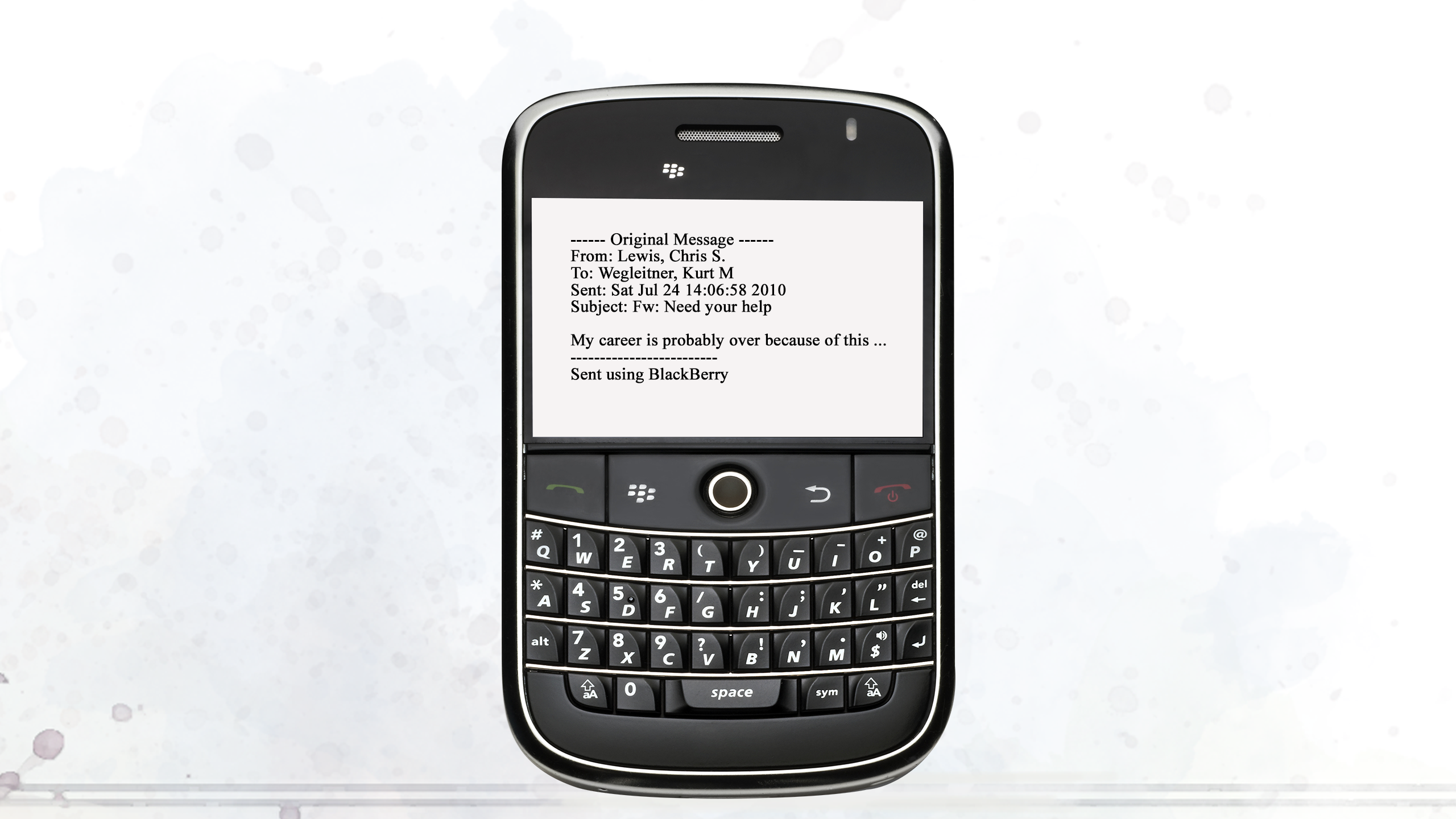

On a summer Saturday just before noon, Christopher Lewis, a top executive at Wells Fargo's wealth management group in Los Angeles, tapped out a lengthy email to a colleague complaining that he had not slept in five days. "Hi Kurt. I promised myself I wouldn't bother you while you are on a well-needed vacation," Lewis messaged Kurt M. Wegleitner, a loan manager at his office, on July 24, 2010. "I really apologize, but I am desperate."

A year and a half earlier, Lewis had taken a new job in Los Angeles running the private bank at one of Wells Fargo's exclusive hubs for high-net-worth investors. The office was among Wells’ largest wealth management operations, one in which celebrities and billionaires trod the halls and where canny advisors, some from modest backgrounds, could join the ranks of the wealthy clients they served by pulling down seven-figure bonuses.

Lewis, who sported short wavy brown hair and a goatee, and prided himself on staying fit (he enjoyed catching at baseball games), quickly won over many in the office. He kept an open-door policy and often stayed late to teach younger colleagues the nuances of credit and lending, both of which can play an outsize role in the creation and maintenance of wealth, especially for clients with large real estate holdings or ambitions to build a real estate portfolio.

But the new position was not what Lewis expected. After what had been, by all accounts, a highly successful quarter-century at Wells in commercial lending, Lewis quickly found himself working on overdrive to counteract what he viewed as systemic fraud, due in part to a casual disregard for federal regulations.

Evidence from Lewis' case opens a window into the operations of its wealth management division amid nearly two years of scandals at the financial services company and its latest efforts to move beyond them. The evidence offers a highly detailed portrait — captured in confidential messages and emails — of a battle that resembles others that unfolded behind the scenes elsewhere at the bank when employees decided to push back against a culture that elevated sales above ethical and legal concerns.

The assertions and allegations in the Lewis case, sometimes shrill and often mundane, reads like a bureaucratic battle for the heart and soul of the bank's high-end financial advisory business. Questionable or unethical sales practices have factored into almost every new controversy that has successively emerged from Wells. In many cases that have become public, those employees who stood up in the name of the bank's Vision and Values statement lost their careers, despite promises from Wells about whistleblower protection. To date, Wells has not offered any evidence to support its claim that it protects company whistleblowers.

In fact, says Michael Fuller, a lawyer who's sued Wells Fargo on behalf of its employees a dozen times, "Wells Fargo will blackball you" if you blow the whistle. "Wells Fargo's insistence on secrecy is just out of control. It's unmatched in the industry." Wells declined to respond to his comments.

Lewis’ claims suggest the problems at Wells may go even deeper than has been revealed. The accusations could mean Wells finds itself facing additional regulatory penalties and perhaps additional scrutiny from the Fed, which took the unprecedented move of restricting the bank’s growth at its current $1.95 trillion asset level due to "widespread consumer abuses."

Earlier this year, Wells paid $114 million to wealth management customers it may have overcharged, contributing to a 37% drop in the group's second-quarter profit. And in response to requests from various federal agencies, Wells initiated internal investigations of its wealth management group.

The bank's many scandals have negatively impacted its wealth management operations, John Shrewsberry, Wells' CFO, told reporters last month on a conference call: "This is a part of the business where reputation matters.”

'Big hitters'

Not long after Lewis took his new job, he discovered that managers in his group would overlook transgressions by "big hitters" if that was what it took to create the perception that the group was outperforming — and deserving of substantial bonuses.

For example, he claimed managers failed to correct issues with a wealthy client's real estate portfolio, forged client signatures and skewed numbers to boost their own income. But he was stymied when he tried to stop or report the problems he found.

"I have been prevented [from issuing] a warning for a banker's negative behavior and continual violations of bank policy," Lewis wrote to Wegleitner, his loan team manager. The message was one of many he shot off to both his bosses and underlings.

Wegleitner took two days to reply to Lewis, urging him to "try not to get too frustrated."

Lewis also reached out to Morrison Creech, Wells Fargo's national head of private banking, based in Charlotte, North Carolina.

"Sorry for sending this email to you, Morrison. However, I love this company and agree completely with [its] Vision and Values. I have thought about what has happened and come to the conclusion I cannot return as [a regional private banking manager] if nobody will listen to me or let me run this group," Lewis, now 57, wrote. "I am fully prepared to walk away from my 26-year career at Wells Fargo as I refuse to be part of this policy" of turning a blind eye to problems with top producers. "I will be extremely relieved if you tell me you will help," he added.

Creech replied urging him to refrain from making a rash decision. "These situations are always complex and the dimensions are many and not always discernible when you are in the middle," he wrote.

He suggested Lewis contact Wells' human resources and ethics hotlines — a strategy managers on the retail side of the business were recommending to employees who’d expressed alarm at being pressured to open fraudulent accounts under bank clients' names. But help was not forthcoming for Lewis; later that year, he was fired, like so many other Wells whistleblowers. The move left him devastated and prompted him to file a complaint with the Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which handles whistleblower claims in these types of cases.

Lewis’ recollection of events from 2008 to 2011 are described in confidential documents obtained by Financial Planning from his OSHA case file. Additional details were learned from interviews with six former co-workers, as well as from a 2016 lawsuit Lewis filed against Wells in Los Angeles Superior Court. When contacted, Lewis declined to discuss the matter. Lewis' lawyer, Creech and Wegleitner did not return calls.

“When I arrived in the office in the mid-morning, Bob informed me … that there was no need to further discuss.”

Chris Lewis, from OSHA case file

Former Wells Fargo wealth management executive

Record whistleblower award

It took OSHA six years to render a decision in the Lewis case — six long years in which Lewis was unable to find work in the financial services industry. The decision in his favor came after Financial Planning and other news organizations published accounts of OSHA's systemic failings in protecting financial services whistleblowers and alleged collusion with large corporate defendants.

OSHA rendered a $5.4 million judgment against Wells — the largest award in the history of OSHA’s whistleblower protection program. This account is the first time Lewis has been identified as the recipient of the award, since federal law dictates that whistleblower awards be kept secret. Financial Planning confirmed his identity from court documents and from Wells.

In addition to ordering Wells to pay Lewis $5.4 million, OSHA also ordered the bank to rehire him — directives the bank refused to comply with and vowed to fight.

But in an about-face in March, the bank settled its eight-year battle with Lewis in a confidential agreement. Whistleblower lawyer Jason Zuckerman, who was not involved with the case, estimated the settlement amount could be in the $10 million range if both sides thought it likely a judge would "order front pay through retirement." He noted that Lewis lost a career in which he might have continued working for years. At the time of Lewis’ termination, his income topped $350,000, with the chance to earn more with bonuses, according to documents in the OSHA case.

"The parties have reached an agreement," Wells spokeswoman Richele Messick confirms. Going forward, "Our top priority is to build trust with all our stakeholders," she adds. Indeed, Wells' recent troubles have been of such breadth and depth that it recently started telling customers it is rebooting itself — the company’s new national advertising campaign notes it was established in 1852, but “re-established in 2018 with a recommitment to customers [and] working to earn back your trust.”

Desperation, then double cross

Two weeks before his last-ditch email to Wegleitner, Lewis began working with one of his direct reports, project manager Ruby Huey, to determine how to address problems he was having with Wells private banker James K. Madden.

Neither Huey, who has left Wells, nor Madden returned calls seeking comment, but Keith Comrie, who was a private mortgage banker working alongside all three in the Los Angeles office, did. Comrie described Madden as a young, ambitious

banker who, soon after getting the job, moved a huge couch into his office, which he decorated with elaborate care. "He was like a big show-off," Comrie says.

"Chris was trying to reel him in and let him become a good banker," he says, by trying to teach Madden the nuances of lending and credit.

In the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession, according to Lewis' lawsuit, the wealth management group became obsessed with increasing its real estate loan portfolios.

Lewis tried to persuade bankers like Madden that mastering the intricacies of lending would make them better at sales, Comrie says, but most balked at the amount of study. Eventually, a frustrated Lewis described himself in an email

to Creech as being surrounded by "an army of bankers that have minimal credit skills."

That posed a problem, given Wells' new direction at the time. The bank brought in Lewis "to help manage and grow the assets of the Los Angeles office — with instructions to specifically grow the residential and commercial loan portfolio, whose growth had become stagnant," the suit says.

Yet in pursuit of that growth, Madden had gone too far, Lewis claimed.

Madden allegedly engaged in work-out negotiations with customers on two commercial loans in default, although Lewis said Madden had no experience in loan underwriting, nor authority to negotiate lending deals with clients. Lewis claimed Madden also misled

Wells Fargo's credit staff, disclosed confidential client information without permission and made "graphic sexual comments" about a female banker. These activities "created real risk for the bank," Lewis claimed,

adding that they were symptomatic of problems elsewhere in the group.

"Let's fucking get rid of him. I'll support you," said Robert Roszkos, the head of the wealth management group and Lewis’ boss, as Lewis recounted to Wegleitner in the email.

"Bob and I then agreed to meet the next morning (Monday) and together address [the accusations] with James," Lewis told Wegleitner.

But that’s not what happened. Rather, Lewis said, Roszkos met with Madden on his own. "When I arrived in the office in the mid-morning," Lewis wrote, "Bob informed me … that there was no need to further discuss."

Other people in the group began calling Lewis, telling him that Madden was saying, "I met with Bob. Lewis can't do shit to me."

"I can't believe this situation was allowed to happen," Lewis told Wegleitner.

While Roszkos wouldn’t discuss the case when contacted by Financial Planning, he forcefully disagreed with Lewis' characterization of events in their email exchanges. "Your comments about my support or lack

thereof as it relates to James [are] totally inaccurate!!!," Roszkos wrote to Lewis. He added: "You did not give me an opportunity to share my thoughts." Roszkos asked to meet in person, noting, "I deserve the

professional courtesy to respond to your comments."

Lewis countered he did not want to rehash a matter they’d discussed multiple times and instead insisted on action from Roszkos.

"The overwhelming consensus [within the wealth management group] has always been that there a few 'bad apples,' which are poisonous to the group, but protected by management because they bring in revenue," Lewis emailed later that day. "Their impression is that what happened with James is another example of that protection. This is not a statement — it is what I am hearing from the people who have communicated with me. O.K., Bob, this is the problem with the L.A. office. It is important that you don't question the accuracy or importance of this statement — as it came from virtually everyone, repeatedly. I have spoken with you about this many times and you have doubted me and done nothing except question if I am correct. Wholeheartedly acting on this will show everyone that you care, prove that you and I can communicate and will satisfy my concern."

Four days later, Roszkos again challenged Lewis' impression of his handling of issues with Madden and said he’d help Lewis address them.

"It appears you believe I have addressed these items with him," Roszkos wrote to Lewis about Madden. "This is incorrect."

"I expect you to address the performance concerns related to his job responsibilities," Roszkos continued. "I do expect that I review the Informal Warning document and ensure you have reviewed the document with HR as well, prior to it being delivered to James. It is important that the supporting documentation is in order before delivering a counseling document. We can discuss this in more detail and how I might be able to participate in the process when you return to the office."

The accusations are "absolutely, categorically untrue."

Tricia Littman, former senior private banker who worked for Lewis in the private bank

‘Climate survey’

Though a seeming overture, the email preceded further estrangement between the two. The next day, Roszkos told Lewis he was ordering a "climate survey" to assess Lewis' leadership of the wealth management group.

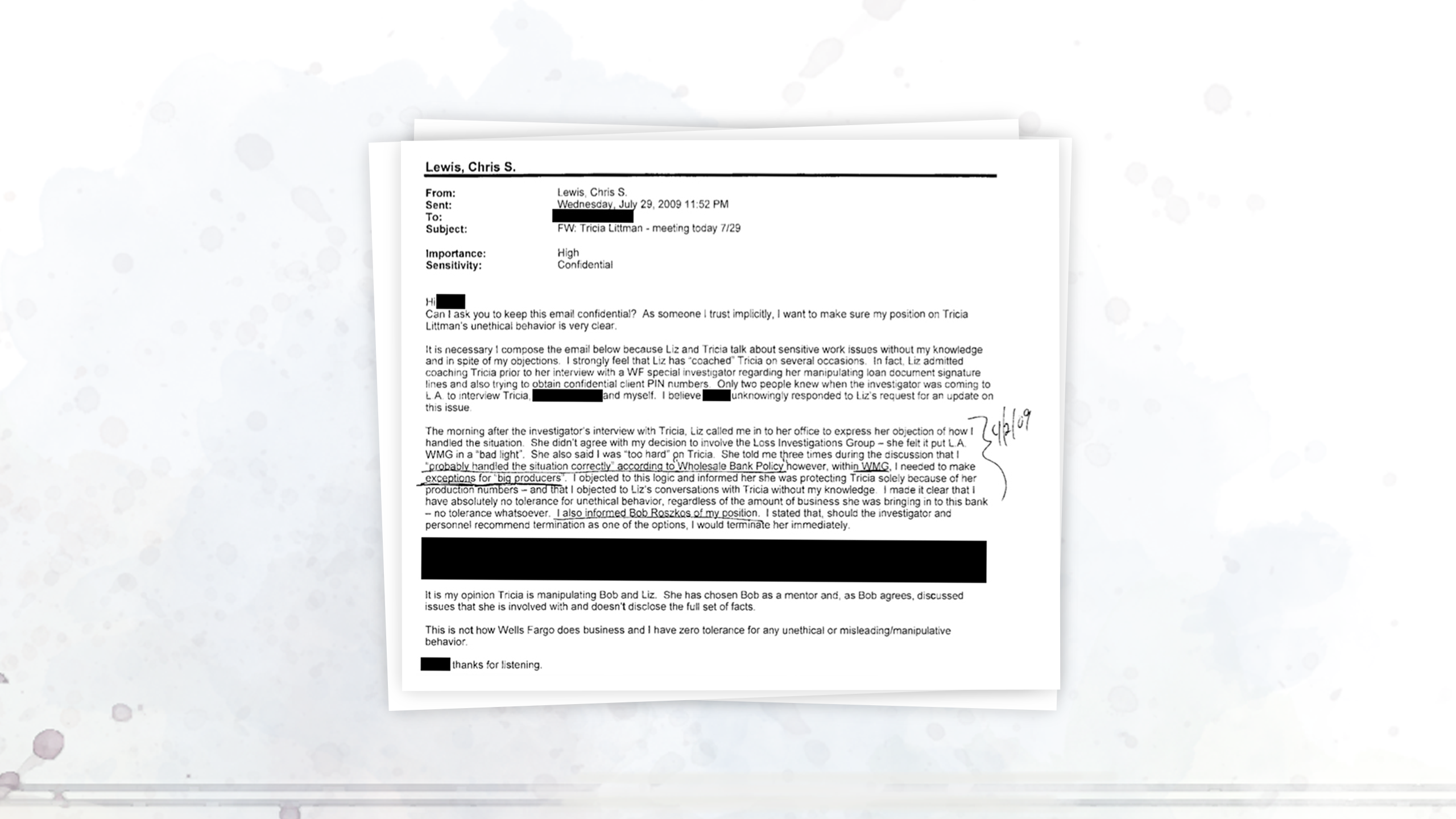

At the same time, Lewis also was having difficulty dealing with another private banker, Tricia Littman.

Ultimately, Lewis tried to have Littman fired for allegedly forging client signatures on documents and trying to manipulate Wells’ computer system to reveal client account passwords, according to his lawsuit. He also claimed that Littman, with the cooperation of Lewis' predecessor, Elizabeth Chai-Chang, had for years withheld problems from the firm regarding the real estate assets underlying a client’s $38 million credit portfolio. Lewis says Littman did not inform the bank about material changes in the portfolio of Beverly Hills-based real estate developer Elias Shokrian.

Wells Fargo did "about five or six loans for us,” Shokrian says in an interview. Amid the Great Recession," one of our major tenants had vacated." A "heated conversation" with Lewis ensued: "I said, 'What is your problem? My payments are like clockwork and the income on the property still services the loan,'" Shokrian recalls.

When the loan was being finalized, Littman had told him that, if the vacancy rate went too high, he'd need additional collateral. "She told me, 'Don't worry about it. It's never going to be exercised by the bank.' But that's exactly what happened," Shokrian says.

Lewis took issue with Littman and Chai-Chang allegedly concealing a variety of problems in Shokrian's portfolio.

Struggling with the situation, Lewis turned to Ken Peterson, Wells' chief credit officer, for advice. Interviewed recently by Financial Planning about that period, Peterson says that, if any banker was routinely concealing information from the bank, then Lewis was right to take decisive action.

"If somebody did that, I'd fire them on the spot," says Peterson, who retired eight years ago from Wells after 29 years there, and is now a consultant in Malibu, California.

Shokrian remains satisfied with Littman; indeed, he has remained a client over the years following her moves from Wells to IDB Bank to Citizens Bank. Shokrian describes Littman as "aggressive" on behalf of her clients. While at Wells, he says, "I guess she had sort of tried to protect us against the bank and maybe they were not happy with that."

Regarding Lewis’ accusations against her, Littman calls them "absolutely, categorically untrue. … He wasn't fired over my stuff or anything that had to do with me." She declined to elaborate, citing a confidentiality agreement with Wells. Chai-Chang, whose LinkedIn page indicates she still works for Wells in Los Angeles as a senior vice president in private banking, did not return calls to her office or mobile phone.

Emails included in the OSHA case file show at least two bankers who Lewis managed asking for his help in figuring out how to deal with issues regarding Littman's handling of client accounts.

"I made it clear that I have absolutely no tolerance for unethical behavior," Lewis wrote about Littman to another colleague, "regardless of the amount of business she was bringing in to this bank — no tolerance

whatsoever."

Exceptions for ‘big producers’

As with Roszkos' treatment of Madden, Lewis accused Chai-Chang of protecting Littman because she brought in strong revenue. Chai-Chang had disagreed with Lewis' decision to reclassify Shokrian's entire portfolio as at-risk in accordance with banking rules, which would have negatively impacted performance metrics, Lewis wrote in a separate email.

"She felt it put [the] Los Angeles wealth management group in a 'bad light.' She also said I was 'too hard' on Tricia. She told me three times during the discussion that I 'probably handled the situation correctly,' according to wholesale bank policy, however, within [the] wealth management group, I needed to make exceptions for 'big producers.' "

By not disclosing problems in the loan portfolio — such as properties Littman said were fully rented when they were vacant, or where anchor tenants had moved out — Littman and Chai-Chang were able to keep their annual bonuses and conceal problems within the wealth management group from regulators, Lewis' suit claims.

"It was all based on that bonus. I was told many times that if we don't get these deals done and meet our goals, we are not going to make our bonuses," Comrie says. "It was a culture of making money, making more money and then making more money."

Instead of heeding Lewis' concerns, Roszkos allowed Chai-Chang to take over Lewis’ review of the Shokrian portfolio. Chai-Chang accused Lewis of pursuing a "vendetta" against Littman, according to his lawsuit.

"I was shocked and not shocked," says another former Wells employee who worked in the private bank at that time, and who asked not to be identified to avoid career repercussions. "Shocked that they would actually [fire Lewis] for doing the right thing after he had been with the bank for 26 years, and not shocked because the private bank is a place where misbehavior is widely accepted if you bring in the revenue." Before coming to Wells, "I had never seen that kind of behavior acceptable anywhere else, no matter what kind of revenue you produced," the banker adds.

By August, Lewis threatened to try to contact Wells’ board of directors regarding his concerns.

"If no one wants to sit down with me and review these violations, I am going to the board," he wrote in an email. "This is bank fraud!"

'Job search leave'

Soon after, Roszkos placed Lewis on “job search leave." He could pursue another job at Wells Fargo, but only if he signed a confidentiality agreement. He refused, even though another Wells division wanted to offer him a job.

The confidentiality agreement contradicts Wells' oft-repeated recent public statements, such as

one made last August that proclaimed: "If team members ever see activity that is inconsistent with our Code of Ethics and Business Conduct, we encourage them to report it immediately."`

Messick, the Wells spokeswoman, said last year that “we are committed to providing a retaliation-free workplace where all team members feel comfortable raising their hand and expressing a concern. … Anything less is unacceptable."

She added that Wells' ethics policy has remained the same for nearly a decade.

Yet the agreement Lewis refused to sign stipulated the opposite: “If you are asked by an internal Wells Fargo manager or team member about your situation you can respond with a statement to the effect that you are pursuing another opportunity within the firm or one that more closely aligns with your strengths. ... You agree that you shall not disclose to any person or entity at any time or in any manner, directly or indirectly, any information relating to the operations of Wells Fargo which has not already been disclosed to the general public. ... If you breach any of these confidentiality requirements, you understand that your paid leave will end immediately … and your resignation with Wells Fargo will be immediately processed.”

Lewis "could continue to have a lucrative career at the bank as long as he agreed to keep quiet about the bank's banking violations," his lawsuit alleges.

Not only does the gag order expose Wells' "whistleblower rhetoric as false advertising," says Tom Devine, a whistleblower advocate and one of the country's foremost experts in whistleblower laws (who is not involved

in Lewis' case), it "flatly violates the anti-gag provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley whistleblower law and SEC rules that enforce Dodd-Frank whistleblower laws." Wells did not respond to Devine’s comments.

Connection to future CEO

For two years, as his conflict was unwinding, Lewis occupied an office two floors below Tim Sloan, the executive who succeeded John Stumpf, Wells' embattled CEO. Sloan would invite colleagues from Lewis' floor to company events

at his home, recalls Comrie, who says he attended twice.

"He was a nice guy, brilliant, so personable," Comrie says of Sloan, who he says once referred clients to him after Comrie got an important loan approved at his request. Comrie says he didn't know if Sloan was aware

of the allegations of fraud in the group Lewis managed, although Sloan ran the bank's real estate group for years while Lewis' worked in commercial lending.

However, two former senior colleagues of Lewis’ say he repeatedly told Sloan directly of the extent of the problems. One of the bankers who asked not to be named said Sloan may have been unable to do anything about Lewis' predicament. Lewis was working in wealth management, a separate world from wholesale banking, the banker said.

That said, when Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas) asked Sloan last October during Capitol Hill testimony about the likelihood of other scandals emerging from the bank, Sloan replied, "Well, senator, I think it's relatively low."

He did not mention the Lewis case, which was pending at the time.

Wells declined to answer questions about whether Sloan had been aware of Lewis' whistleblowing.

A year after Lewis moved to wealth management, Roszkos co-authored a Wells commendation in 2009 marking Lewis' 25 years with the bank. It came out around the time Roszkos completed Lewis' first annual performance review in

his new position, which said he "produced very strong financial sales results," having exceeded his revenue goal for the private bank by 44%. The commendation described Lewis as a "commercial real estate guru" and

a "mentor" who elevated "everyone to an even higher level of excellence." It was co-authored by Jay Welker, now the San Francisco area president of Wells’ private bank. Welker did not return calls to his

office.

Yet months later, the "climate survey" that Roszkos ordered of the operations Lewis supervised found that Lewis "doesn't seem to care about others," "does not have the affection and support of staff members"

and "creates fear," according to the OSHA documents.

Protests hit home

The San Marino, California, home of Wells Fargo CEO Tim Sloan is a frequent gathering place for protesters, including some who used to work for the company.

Termination

Roszkos fired Lewis on Dec. 4, 2010, after he had spent months on job search leave (and, it turns out, on his 50th birthday).

"When I heard about it I was like, 'You are kidding me,' " one of the bankers who worked with Lewis said recently. "I couldn't believe they would treat someone so disrespectfully, so horribly. Chris didn't

deserve what happened to him."

Comrie says, "I thought the way that was handled was totally unfair to Chris. … Chris was wronged."

During Comrie’s time at Wells, he says he was both awed and extremely grateful to find himself working at the bank after being raised as a youngster in Jamaica without electricity or running water. He retired five years ago,

and says he is now going public with his experience at the bank to help Lewis.

"I really love the guy," says Comrie, a tall, striking 60-year-old who looks far younger. "I sort of worship him only because he is so smart. He is one of the most intelligent persons I have ever met. He was warm and inviting. I never reported to him, so maybe James and Trish had a different view of him. I know he was patient. He was always patient with me and he was always willing to teach me."

When Comrie was learning about underwriting, he says he sometimes worked into the evening with Lewis out of Lewis' home in Manhattan Beach. He shared dinners with his family and learned from Lewis how to write in banker's English.

Two years ago, he saw Lewis at the Waikiki, Hawaii, wedding of Wells Fargo banker Kelly Wong, who Lewis also had mentored, and gave him a bear hug.

"He seemed in very good spirits," he says, "but I knew he had to be suffering. He told me he was living off his 401(k). I could not imagine how anybody could be unemployed for that long and still survive. I sense it

was difficult for him to come to the wedding."

After Lewis' departure, Comrie says, things got worse in the wealth management group. Wells increasingly pushed people in the group to charge clients mortgage rate lock extension fees that could range well into the thousands of

dollars, he says, and to close deals at any cost. "There was so much pressure to do those unethical things," Comrie says," and I can't do those things — like charge a client a fee when I'm the one who

was slow getting a job done."

Wells admitted last year it charged 110,000 customers fees to extend mortgage rate locks between 2013 and 2017, while Comrie was there,

even when the bank was the cause of the delays. It pledged to refund a portion of the $98 million it says it charged those borrowers.

A couple of weeks after Lewis was fired, he received still more bad news: Chai-Chang apparently denied a long-pending refinancing of his home mortgage, according to Lewis' lawsuit. Wells told Lewis the decision was made because it could not verify he was employed, OSHA documents show. Due to his termination, "Mr. Lewis has not only sustained catastrophic financial losses, but he has also suffered a serious loss of reputation and emotional distress because of the retaliation and other unlawful conduct alleged herein," his OSHA complaint says.

None of this surprises attorney Michael Fuller, the lawyer who often squares off against Wells in court. Wells is known for tarring the reputations of workers when firing them to render them unemployable, he alleges.

"I can't tell you how many different types of peoples' lives this bank has ruined," Fuller says. "There's no shortage."