When Dana Pollard's client was downsized from the global manufacturing company where she worked as project manager, she was quick to plot her next move: she went back to school.

Six years later, at age 58, she's working in the homeopathic field making no more than what she was earning before her hiatus from the workforce. Only now she's saddled with $40,000 in student loans that she didn't have previously.

While she suffered a financial setback that will delay her retirement by many years, she should nevertheless count her blessings, says Pollard, an adviser with Wells Fargo Advisors in Woodbury, Minn. She at least transitioned into a career she enjoys a lot more.

Robert Murphy of Duxbury, Mass., wasn't so lucky. He too had the misfortune of losing his job at a manufacturing company late in life at the age of 52, but he never recovered financially. He instead went bankrupt.

Murphy, now 66, was president of the company when it was sold and moved its operations overseas in 2002. He tried to land another job but the search proved fruitless due in part to a shrinking manufacturing industry and his age, according to court documents.

Not anticipating that he would be unable to find a job or the 2008 financial crisis that destroyed the value of his home, Murphy took out a series of student loans on behalf of his three college-age children in the amount of almost $210,000.

The loans, together with his mortgage and other debt payments, eventually overwhelmed him and led him to file for bankruptcy in 2011. At the age of 61, when most people are getting ready to slide into retirement, Murphy was facing the possibility of not being able to meet even his most basic necessities.

A new reality

Murphy and Pollard’s client represent the twin faces of a new dynamic at play among older Americans. One is emblematic of people who realize that they want or need to go back to school to redirect their career and secure their future. The other embodies those who — alarmed by rising college costs — want to help their children with the growing burden of student loans. Whichever side of the coin they're on, they end up with the same shared problem: student debt that could potentially torpedo their retirement.

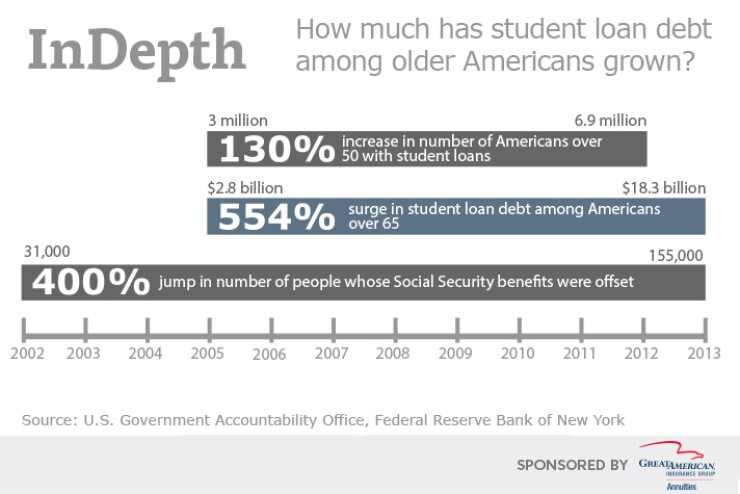

It’s an issue that’s been growing. The number of Americans over the age of 50 with student loan debt more than doubled from 3 million in 2005 to 6.9 million in 2012, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office bore out similar statistics. In 2010, 4% of households headed by people between the ages of 65 to 74 carried student loan debt, up from less than 1% in 2004, according to the government agency. While older Americans account for a relatively small segment of the overall student loan market, their debt is growing much faster than that of younger Americans, soaring to $18.3 billion in 2013 from $2.8 billion in 2005, an alarming six-fold increase.

"It's starting to be something that we're seeing more and more often," adviser Alex Chalekian, founder and CEO of RIA firm Lake Avenue Financial in Pasadena, Calif., says of student loan debt held by retirees or soon-to-be retirees.

Because of their age, older Americans are more likely to default on their loans than younger people who have long time horizons to pay off their student debt, according to the GAO. Almost one in three Americans between the ages of 65 to 74, or 27%, defaulted on their student loans, more than twice the default rate of people under 50. For seniors over 75, the default rate was over 50%.

Social Security garnishment

The repercussions for retirees can be disastrous. People who fail to make good on their student loans are at risk of having a portion of their Social Security checks garnished. In 2013, the government took $150 million from the Social Security checks of people who had student debt, up from $24 million in 2002. Of the 155,000 people who had their checks snipped, 36,000 were over the age of 65.

"They can garnish your wages, your tax returns, your Social Security," says Josh Giuliano, an adviser and certified financial planner with Citizens Bank in Cranston, R.I.

"It was more important for them to see their children graduate from college without debt than it was for them to be debt-free," says Wells Fargo adviser Dana Pollard of a couple in their 60s who decided — foolishly, she thought — to help their kids.

By and large, older Americans incurred the debt for their own education. Almost three in four Americans between the ages of 50 and 64, or 73%, had debt due to mid- or late-career retraining, according to the GAO. The remaining 27% carried debt as a result of loans taken out for their children.

Giuliano often sees clients who carry loans both for themselves and their children, a group he refers to as the sandwich generation.

"They're getting caught with debt at a later age than they're used to and at the same time children — with the cost of college being dramatically higher than what it was generations ago—are now needing more and more help getting loans," says Giuliano.

Sandwich generation

One such client, now 62, is paying down some $30,000 in student loans that he took out at 50 to pursue a four-year college degree, while simultaneously helping his children pay off their college debt. His children unfortunately had trouble finding gainful employment, and since he co-signed their loans, he is on the hook for their loan payments.

The debt load was such that Giuliano's client was unable to put any money into his 401(k) plan for eight to 10 years, which dramatically set him back on his retirement savings goals. He now doesn't have many options other than having to work much longer than he originally anticipated, Giuliano says.

While Pollard rarely comes across clients with late-life education loans, she wouldn't be surprised if she started seeing them more often. People are living longer and they're more comfortable with debt than they have been before because of the low interest-rate environment, she notes. "They're willing to take on the debt with the assumption that they'll live long enough to pay that back and enjoy it," she says.

More often than not, she'll have clients come in who are simply trying to help their kids. One couple she advises in their 60s had paid off their mortgage and were set to retire when they suddenly had a change of heart and decided to help their two children finance their college education. Once they saw the price tag, they couldn't help but step in at their own risk, Pollard says.

The couple took out $75,000 in student loans on behalf of their oldest child and mortgaged their home in the amount of $200,000 to pay for the other child's tuition and school expenses.

"It was more important for them to see their children graduate from college without debt than it was for them to be debt-free," Pollard says.

Pollard bemoaned their poor decision. "They really are struggling with money right now. Their retirement is not what they expected," she says. The couple is plunking down $3,000 a month, or half of their monthly income, on mortgage and student loan payments when they could have been traveling and having fun in retirement.

Here's your diploma — now pay up

Parents typically aren't prepared for the sticker shock they experience when their children get accepted to reputable schools, says Chalekian. "Most of these kids aren't getting out of school with less than a quarter of a million dollars in school debt," he says.

Like Pollard, Chalekian cautions parents against taking out student loans for their children, saying that when they crunch the numbers, it could push out their retirement for another 10 years.

"It was a tough decision because obviously as a parent you want to help your kids as much as possible," says adviser Alex Chalekian of a client who decided not to help his kids pay their student loans after realizing he’d have to work another decade.

Even with that knowledge, parents will oftentimes insist on helping their children, while putting their own retirement on hold. In a rare instance, one of Chalekian’s clients reconsidered. He wanted to help his two children pay off their considerable student loans, but when he realized he’d have to work another decade, he told his children that physically he wouldn’t be able to do it. The client had worked his entire career at an oil refinery.

"It was a tough decision because obviously as a parent you want to help your kids as much as possible," says Chalekian.

The children had a combined student debt of $250,000, which meant that the client would have had to siphon about $500,000 out of his IRA to cover federal and state taxes on the $250,000 withdrawal.

Parents should have their children exhaust any and all merit programs, grants and scholarship opportunities, which would not only reduce the amount of their loans but also increase their chances of getting them, says Giuliano. He also advises parents not to co-sign student loans if they don't have to. “That’s not to say that they can't help their children pay for the loan down the road, but then they won’t have the debt obligation on them as well,” says Giuliano.

Advisers urge clients to carefully consider taking out student loans even for themselves. If they expect this would increase their earning potential enough to justify their taking on the additional debt, it makes sense, says Giuliano. Otherwise, they should consider other alternatives, such as getting the job they seek first and seeing if the employer might pay for the education.

While Chalekian encourages career changers to pursue additional education if it will help them grow professionally, he cautions them to be careful. “There are many programs, especially for working adults, that I think take advantage of the situation and charge outrageous tuition,” he says.

Clients struggling with student debt should make sure that the interest rates on their loans are competitive. Rates on student loans were around 8% to 9% four to six years ago, so debtors may be able to cut that to somewhere in the 4% to 5% range, saving themselves hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars a month, according to Giuliano.

In addition to refinancing, clients should look to modify the terms of their loans so that monthly payments become less burdensome. In particular, they should explore income-based repayment plans, which allow debtors to restructure their loans based on income, says Giuliano.

Discharging loans next to impossible

Clients need to do their homework because student loan debt is nearly impossible to discharge. Because the government can garnish not only a client's Social Security check but also their wages, tax returns and in certain states their driver’s license and professional designations, it can trap clients in a vicious cycle that they're unlikely to get out of.

“Imagine that you're struggling in life and trying to work three jobs to help keep current on all your debt and because of falling behind you lose a designation and your driver’s license," Giuliano says. "Now you’ve also hurt your ability to earn money to help pay this debt off."

Aside from death and disability, clients have almost no way to free themselves of their loan obligations. If they worked for the Peace Corps or AmeriCorps or as doctors, nurses and health professionals in designated underprivileged areas, they may be able to have their student loans forgiven, according to Giuliano.

While extremely rare, they may also be able to discharge the debt through a bankruptcy proceeding, as did Murphy. After an exhaustive court battle, Murphy reached a settlement with the Department of Education and the Educational Credit Management Corp. in June that extinguished the more than $246,000 he had outstanding on student loans taken out for his children.

Murphy argued that paying back the debt would pose an undue hardship given his age and limited ability to earn income. To retire the debt over 30 years, he’d need a monthly income of $5,490 or nearly $66,000 a year, an unrealistic goal for a man who had been unemployed since 2002.

“The probability of becoming a high-wage earner again is highly unlikely given the length of his unemployment, the perception of potential employers that his skills have atrophied, his age, and the decline in the manufacturing industry in general,” Murphy, acting as his own attorney, writes in a brief.

During his trial in 2013 when he was 62, Murphy noted that he had only eight to 13 years remaining in his working life, and his most likely source of income would be his Social Security checks, which amounted to roughly $27,000 a year.

“It is unlikely that the level of income that could be generated over the next eight to 13 years would even come close to retiring over $246,000 in outstanding student loans,” Murphy writes.

The settlement Murphy achieved is unusual as the law has been very strict about the repayment of student loans. Still, some legal experts are hopeful that the law might ease up for older Americans in or nearing retirement. "It is very difficult, but I do believe the bankruptcy judges are trying to find ways to deal with it because it's so oppressive," Donald Lassman, the bankruptcy trustee for Murphy, says of senior student loan debt. "It's impossible to repay."