COVID has taken a particularly acute toll on women with children and careers. New data suggests just how steep the cost has been, and how the pandemic altered their long-term financial planning.

In 2020, the first year of the pandemic, nearly nine in 10, or 89%, of estate planners said that their women clients had either lost jobs, seen their wages cut or left the workforce entirely, according to a

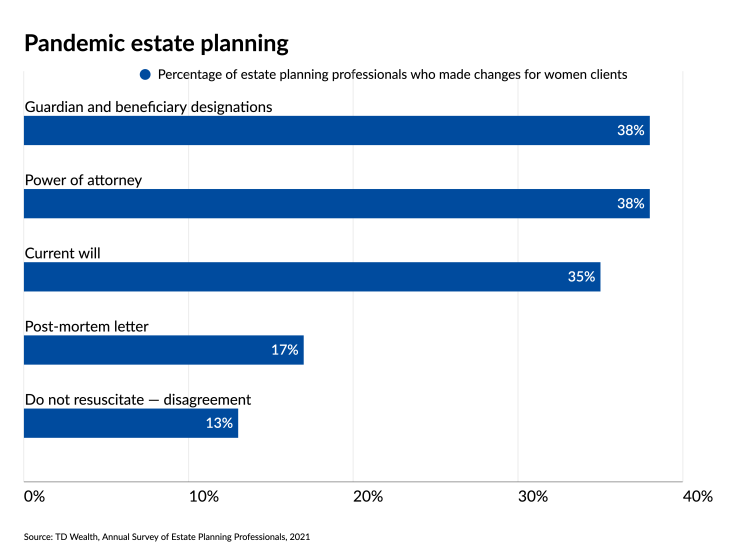

The loss of income prompted estate professionals to alter clients’ plans for bequests. Specifically, nearly four in 10 planners changed guardian and beneficiary designations or power-of-attorney provisions — a reflection of the impact that COVID-19’s deadly toll has had on families, whether directly, through a family member who died, or indirectly, through heightened fear of succumbing to the virus.

Additionally, more than one in three estate planners altered women’s current wills (the study did not say how). Nearly one in five created or altered postmortem letters, a document that accompanies a will and outlines for executors and heirs where assets and important records are located, as well as the advisors, accountants and lawyers involved in drawing up a will. Grimly, 13% of planners with female clients made provisions to challenge a doctor’s do-not-resuscitate order, possibly a reflection of the role that ventilators have played in saving the lives of some COVID-stricken patients.

The study adds to the growing body of data on how sharply the pandemic has set working women back financially. TD Wealth, part of Toronto-based TD Bank, commissioned its poll of 142 certified estate planners, estate planning attorneys, trust officers, charitable giving professionals, insurance advisors, elder law specialists, wealth management professionals and non-profit advisors about pandemic-related changes their women clients were making.

The bank’s prior studies pre-dated COVID and focused largely on the impact of divorce, family conflicts and shifting tax laws. Still, the current study found that increasing healthcare costs and generally higher life expectancies emerged as the biggest issues in estate planning during the pandemic, with nearly one in four respondents citing them as the biggest threat, more than triple the number in 2019. One third of women aged 65 who are in excellent health can expect to be alive at

In March, McKinsey

Gail Cohen, the board chairman of Fiduciary Trust International in New York, says that the pandemic marks “the first time ever that women are dropping out of the workforce more than men.” What she calls “the three Ds” — divorce, death and debt — had a new, unwanted companion: loss of income. “The pandemic has been much harder on women than on men,” she adds. “We know the reasons.”

Not surprisingly, parents of children under age 10, whether single or in dual-career households, have fared the worst. With schools closed and child care arrangements upended, working women appeared more ready than ever to throw in the towel on their jobs and the workforce. McKinsey

Kalimah White, a vice president and wealth strategist at TD Wealth, calls the pandemic-driven downward shift in jobs and employment for women a “she-cession,” adding that it hammered home the role of increasing longevity in a family’s financial future.

Cohen argues that COVID, not looming tax hikes, is the top reason advisors should reach out to their women clients, whether they are single or part of a two-income household that may have lost a job. “If there were two incomes that kept them moving towards mass affluence, and all of a sudden one of those incomes drops, that’s major,” she says. “From an estate and financial planning perspective, there’s a real opportunity here to really help these women.