A few months ago, I went to the AICPA's personal financial planning conference in Las Vegas, and there was an interesting contrast between what was going on at the gaming tables and the investment discussions we were having during the meeting. At the same time, I was participating in an online conversation about macroeconomics on the Financial Planning discussion forums when the discussion veered unpredictably into a heated debate about beating the market, and the pros and cons of market timing.

There's a lot we can learn from the contrasts between gambling and investing. Exploring them might not only inform conversations with clients, but also clarify the profession's role in tending client portfolios.

LOOKING AT THE ODDS

The first and most obvious contrast between gambling and investing is the odds. Years ago, I created a spreadsheet that calculated, down to two decimal places, the odds of various bets at a casino. The roulette wheel was pretty easy, blackjack and craps were somewhat harder, but at the end of the exercise, I determined that the closest thing to a 50-50 bet in a Vegas casino is the Don't Pass line at the craps table, where you consistently bet against whomever is rolling the dice.

The odds for that particular bet are something like 49.32-50.68, which in the real world means that if you play long enough, you'll eventually lose roughly 1.3 cents for every dollar you put on the table. It's pretty cheap entertainment, but not exactly a fast road to riches. And I'm told that the veteran gamblers look at you funny when you stick with the Don't Pass line roll after roll after roll, especially when you shriek with happy excitement every time they crap out.

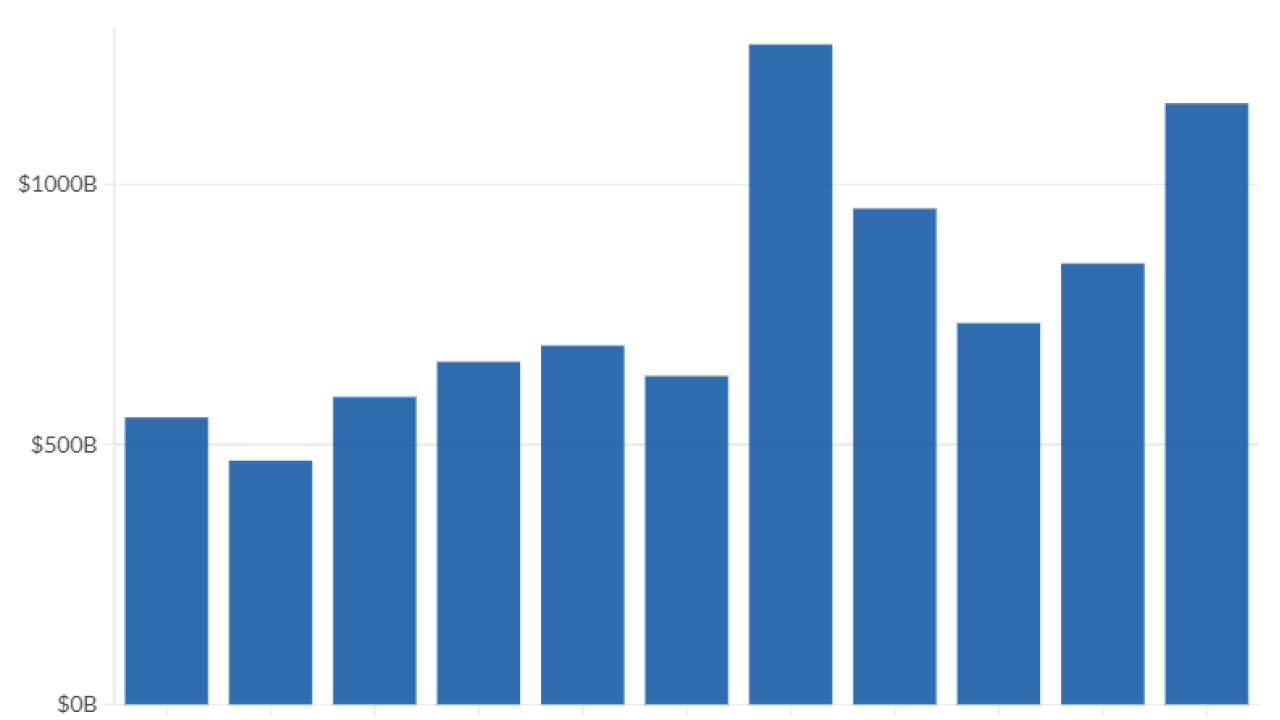

The best wager in Vegas pales next to the odds at the investment "casino," where long-term returns of U.S. large-cap stocks (dividends included) have averaged anywhere from 9.4% a year (if you're counting since the end of 1899) to 11.2% annually (if you're just counting the last 25 years). Even the Lost Decade, which is comparable to the worst run of luck you're ever likely to encounter in the casino, offered odds in your favor.

True, the Wilshire 5000 was off -0.2% annually over the 10 years ending Dec. 31, 2009, but Wilshire's mid-cap index gained 4.6% a year, and its small-cap index was up 4.3% annually. The EAFE developed markets index also lost 1.1% each year during that time.

But if your clients rebalanced among all these asset classes at least annually, and at best opportunistically, reinvested dividends and included a reasonable percentage of bonds in the portfolio, they would have finished the Lost Decade with aggregate returns somewhere north of 3% a year. Maybe you're not shrieking in triumph, but at least you're beating the inflation rate and growing your purchasing power.

So the first beneficial role that the investment advisor plays in a client's financial life is to make sure that he or she is still "playing" in the "investment casino," since the longer you play, and the more astutely you do it (by reinvesting dividends, rebalancing and staying diversified, for example), the more you can grow the chips on the table. And, as it happens, this is where a lot of market "players," operating on their own, don't seem to quite measure up.

Based on fund-of-flows data, Morningstar has calculated that the average investor gets about 1.5 percentage points less a year than the market offers them. This happens because they are moving in and out of the market at the wrong times, chasing hot funds just as they're about to cool off and abandoning underperforming funds right before a turnaround takes place. This is normal human behavior, of course.

In the casino, too, you see a lot of people putting money on those dumb sucker bets at the craps table, not knowing how to play their blackjack cards to best advantage or sticking coins in the slots, where the odds are preordained to work against them. (I suspect that if everybody stuck to the "Don't Pass" line on the craps table, the casinos would quickly go out of business.)

WINNERS AND LOSERS

But what does this discussion have to do with market timing and beating the market? If we define market timing as being either in or out of the market based on some set of signals, the first thing to notice is that this activity reverses those positive stock market odds.

To the extent that we are out of the market, we're making a bet that the indexes won't go up during that time-and since the markets tend to go up 60%-70% of the time (depending on the asset class), this turns the market's strong positive odds to strong negative ones. It takes a lot of skill to overcome the unfavorable odds that pure market timers have set for themselves with their actions.

And yet, I think we've all seen the stories of professional gamblers who are banished from casinos because they seem to win more than they lose. There aren't many of them, but they include mathematics professors who count cards at the blackjack tables and astute gamblers who limit their losses on each visit.

When they get ahead and start playing with the house money, they raise the stakes and ride their luck-winning thousands or tens of thousands when their luck is good. These rare people are capable of overcoming lousy odds with their unusual skills.

They seem to have counterparts in the investing world. I don't know of any market timers who have routinely beaten the market (those odds may be too greatly stacked against them), but there are interesting examples of financial advisors who pay attention to the prices of assets versus their historical averages, sell into manias and buy when the markets are gloomy. They get more than their fair share of returns by doing the opposite of what individual investors do, and I think our professional debates treat these people quite shabbily.

Because most of us lack this peculiar skill, we deny that anybody else could possibly have it and forbid professional discussions about the subject. That is unwise and short-sighted on our part.

STAYING IN THE GAME

It takes uncommon skill to keep those emotional creatures we call "clients" consistently playing in the investment market casino, where the odds work in their favor despite setbacks and peculiar runs of luck. If the Morningstar data can be applied longer term (and I suspect it may be an underestimate), then simply keeping your clients invested may be the most valuable investment-related service that you provide to them. Everything else-from selecting above-average mutual fund managers to tactical asset allocation to market timing-requires a peculiar talent to deliver less value with less certainty.

If we can stipulate up front which skills are primary and which are secondary, then perhaps we can have an honest discussion about those peculiar investment talents, how they work and how (or if) we can recognize people who have them. In my ideal world, the bouncers would keep everybody out of the casinos except the consistent winners, and every financial advisor would help their clients win more at the investment casino than the average investor.

Beyond that, there's an interesting discussion, waiting to be started, about all the other things we can do to influence those much more complicated investment casino odds. We should start talking about what strange or unusual talents we would need to have to put those odds even more in your clients' favor.

Bob Veres is editor of Inside Information (www.bobveres.com), which helps advisors become more effective, efficient and successful by identifying best practices in practice management and client services.