All advisors are expected to assess clients' risk tolerance before designing their portfolios. We diligently conduct this assessment, yet we are shocked, simply shocked, when our clients' behavior doesn't match their self-reported risk tolerance. How do we know when this happens? We get a call from a client, panic in his or her voice, insisting that we modify a portfolio in reaction to market fluctuations.

Why are we still getting those calls, and worse yet, why are we still surprised by them? We can blame the traditional risk assessment tool that most advisors use. Yes, it's been validated by research, has been shown to measure risk tolerance reliably, is used by many of your peers and comes with some impressive statistics, charts and graphs. We use that risk tolerance score, along with a consideration of the client's assets, desired rate of return, income needs and age to place the client into an investment objective category, such as aggressive growth, growth and income, balanced, income or some other iteration.

For most advisors, this is where the risk tolerance assessment process ends. The reality is that the traditional risk tolerance assessment is mostly a "CYA" procedure. Unfortunately, the psychology of risk tolerance is more complicated than what today's questionnaires measure. Risk tolerance is a multidimensional, fluid construct affected by many factors.

Seasoned advisors agree there is often a big difference between what clients report as their risk tolerance and their real risk toleranceas manifested in their psychological capacity to withstand real-life market fluctuations. Ron Sages, Ph.D., a wealth management advisor and personal financial planning researcher in Greenwich, Conn., agrees that standard risk tolerance assessments fail to measure the behavioral aspects of risk tolerance. "When reality hits, as it did in 2008, behavioral facets of risk, which go far beyond self-reporting of one's willingness to accept risk, are much more important to a client's bottom line," says Sages, who is also president of Chapin Asset Management.

Sages recalls a married client couple in their early 60s approaching retirement, identified by traditional assessments as growth and income investors. In 2008, their portfolio dropped significantly and they called Sages in a panic. Despite his recommendations to the contrary, the couple insisted on moving to a more conservative portfolio.

"They were scared," Sages says. "They were convinced their retirement assets were going to dwindle to zero and sold equities at the wrong time, locking in their loss. They had an anchor point and when their portfolio dipped below that mark, they saw it as a financial catastrophe."

Behavioral Signs

In addition to the traditional criteria used to evaluate a client's risk profilesuch as self-reported willingness to tolerate risk, age, time horizon for investments and liquidity needsthere are many other psychological factors to take into consideration when evaluating a client's true tolerance for risk. These include:

Client's gender. In general, men tend to report more confidence in their investing acumen and higher levels of risk tolerance. However, research suggests that they have the same risk capacity as women. As such, your male clients may be exaggerating their true tolerance for risk.

Planner's gender. The gender of the planner also has a significant impact on a client's reported willingness to tolerate risk. In their research, Sonya Britt, an assistant professor and program director of personal financial planning at Kansas State University and John Grable, a financial planning professor at the University of Georgia, found that men and women both report higher levels of risk tolerance when working with an advisor of the opposite sex.

"People seem to have an innate preference to be seen as attractive to members of the opposite sex, regardless of their relationship status. One way to demonstrate this attractiveness is by reporting higher tolerance to risk," Britt says.

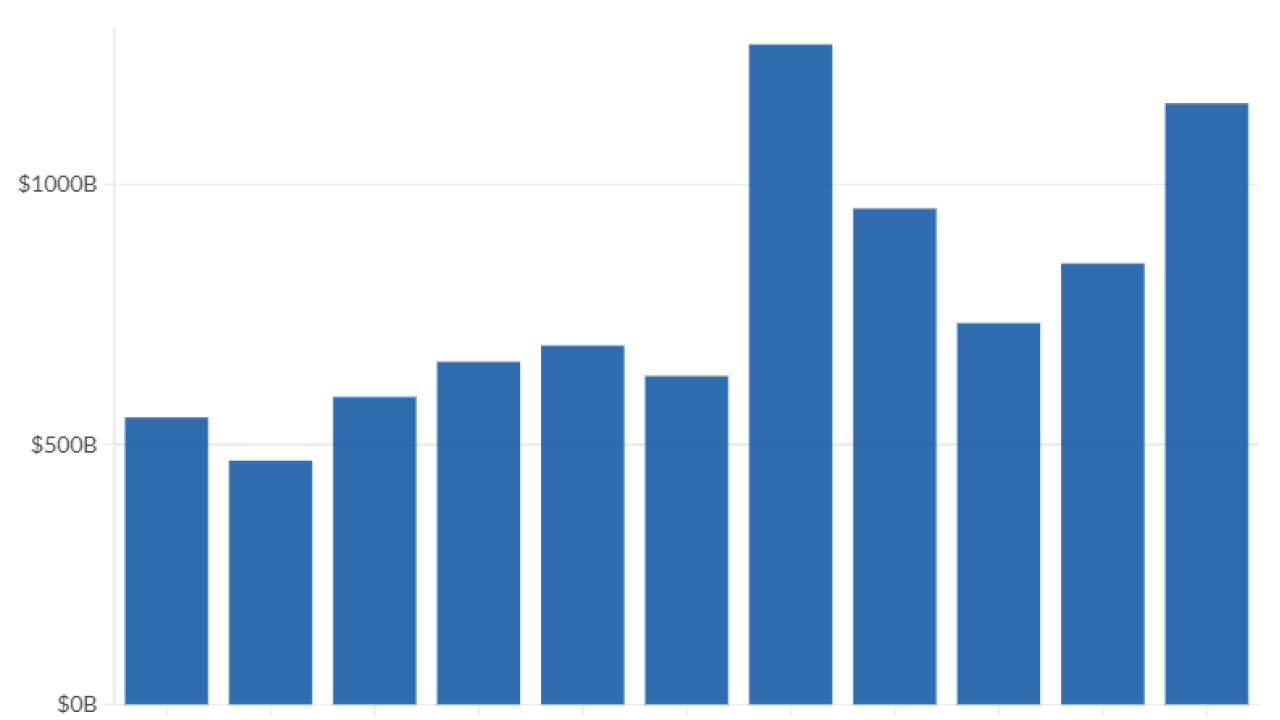

Risk perception. How an individual perceives risk can be based on many factors, ranging from someone's current mood, past experiences, current market conditions and recent performance of a particular asset class. For example, it is common for an individual's tolerance for risk to increase as overall market performance increases. In turn, as market performance decreases, so does the client's willingness to take on risk. As such, the universal and predictable fluctuations in risk tolerance work directly against clients' best interests.

Risk composure. Risk composure relates to how clients actually behave when faced with a financial loss. Knowing how clients reacted to the last market downturns can be one of the best predictors of their true tolerance for risk. If they held firm and waited it out last time, chances are they will do so again. If they bought at the top and sold at the bottom in the past, chances are they will be inclined to do the same again.

Anchoring. People may be willing to take more or less risk based on a financial anchor. For example, if clients consider financial success to be a portfolio of $1 million, they may prefer a growth approach. However, if their portfolio dips below the $1 million mark, they may get anxious and demand a more conservative asset allocation.

To assess a client's anchoring, an advisor might ask, "Do you have a particular number in mind that defines whether you see yourself as financially successful or secure?" This number can be a powerful predictor of whether a client will panic in a market downturn and can be useful in designing a portfolio consistent with a client's true risk tolerance.

Financial loss. Research shows that an individual's willingness to take risk can increase dramatically after suffering a significant financial loss. In an effort to make up for lost value or time, an individual may want to double down and take on more risk than is prudent.

Best Practices

A big mistake in onboarding prospects is emphasizing recent or historic positive returns. Clients are better served by discussions that highlight the downside of risk to ensure informed consent to investment objectives. The conversation also helps to inoculate clients against inevitable market downturns so they won't panic and sell low. Note that clients react more honestly to illustrations that use actual dollar amounts than those that focus on portfolio percentages.

This conversation can go something like this: "Based on the risk assessment you completed, we would recommend an aggressive growth portfolio. However, while this approach makes the most sense based on your objective data, the portfolio that is really in your best interest comes down to whether you can stay the course during the next market downturn, which could be tomorrow, next month or next year. For example, while this portfolio's best year had a 68% return between March 2009 to February 2010, from March 2008 to February 2009 it lost 46% of its value. For your portfolio of $1 million, this would mean a loss of $460,000.

"Of course this level of risk historically leads to higher returns, but only if we don't make the classic mistake of selling out of fear and can hold for the long term. If you can envision seeing your next statement at $640,000, not insist that we sell and be committed to holding for the long term, then this is the way we should go. If not, then we should design a portfolio with lower risk and lower return."

To novice investors, this discussion might appear to be an attempt to coerce a client to accept a lower-risk portfolio. However, to advisors who still wake up in a cold sweat remembering the events of 2000 and 2008, getting an accurate assessment of a client's risk tolerance is essential.

In the end, risk tolerance is not stable. Rather, advisors should monitor a client's perception of their willingness to accept risk tolerance (which they will tell you) and their actual risk composure (which they will show you in the next market downturn) throughout the relationship. As advisors, we do our clients a disservice if we naively mistake their self-reported risk tolerance for their actual behavioral tolerance to accept portfolio losses.

Brad Klontz, Psy.D., CFP, is a financial psychologist, associate professor

in personal financial planning at Kansas State University

and co-author of four books on the psychology of money.