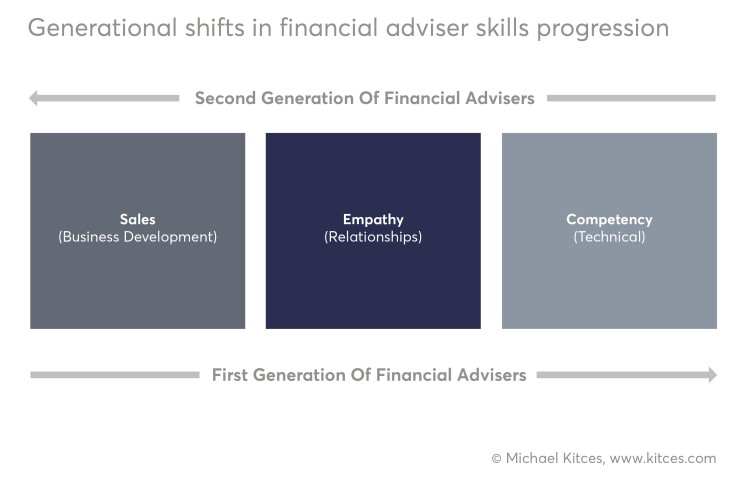

In the early days of financial planning, most advisers needed just one skill for success: salesmanship. When advisers were solely compensated by commissions, if you couldn’t find new prospects to sell to — and actually sell something to them — your income would summarily go to zero.

As advisers have shifted to the AUM model, though, the requisite entry-level skillset has shifted. Now, for many advisers, the key abilities are technical competency to give the right advice, and empathy skills to form and deepen client relationships. Sales- and business-development acumen come later, if at all. And as advisory firms have grown, a skills gap is emerging in the area of business management, which impacts training and developing staff members, as well as the overall execution of the business itself.

For advisers to progress in their own careers, they must expand their expertise across more and more of these skill domains. And for advisory firms themselves, these skills provide a roadmap for where the firm should invest resources to prepare its team for the future.

The original skills progression for advisers

In the early years of advisers, almost no one was actually compensated for dispensing advice. Instead, most were sellers of financial services products — from (door-to-door-sold) insurance policies in the 1960s and ‘70s to tax shelters in the ‘70s and ‘80s to stocks and then mutual funds in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

As a result, the primary skill that someone needed to survive in the early years was the ability to sell. If you couldn’t do business development, prospect for clients or create repeat business, you didn’t make any money. Consequently, you couldn’t validate your sales employment contract, and you were out of the business. Financial services firms had extensive

The subset of salespeople successful enough at cold selling — in an era where most sales were driven by door-to-door knocking and, later, scripted telephone calls — eventually had the opportunity to form deeper relationships. The virtue of deepening a relationship was that it turned someone from a mere sales opportunity into a potential source for

The caveat, however, was that the skillset to form strong relationships with clients and centers of influence was different than just the ability to sell. It required empathy: an ability to be cognizant of the feelings of other people, such that you could adjust your communication style and approach to them. While some people are born with this heightened

For those with good empathy, whether instinctual or learned, it became possible to build a steadier income from repeat/recurring business with existing clients, and the referrals that were generated from those clients and other centers of influence or strategic alliances. This freed up salespeople to no longer spend all their time worrying about when the next client would emerge, and instead take the final step of skills development to actually become an adviser: gaining the technical competency to effectively dispense bona fide financial advice.

Of course, you can’t effectively advise until you have the training and education to know the correct advice to provide. Otherwise, the adviser may give

How AUM has changed training

The advisory profession of the past was all about the skills progression from sales to empathy to technical competency. However, the growth of the AUM model, where recurring advice was provided in exchange for recurring revenue, fundamentally changed this equation. Suddenly, the problem for many rapidly growing advisory firms was that the founders responsible for sales and business development were running out of the capacity to service a growing volume of existing clients. Fortunately, because those existing clients generated recurring revenue in the form of AUM fees, it was feasible to pay a highly skilled adviser to service them.

However, since those firms already had the clients, the traditional skills progression for their advisers was distinct. It was no longer necessary to start with sales and business development, because the firm already had that covered. Instead, the need was for advisers who had the technical competency to deliver advice, and the empathy with which to establish a relationship with a client (and be able to retain them in the future).

The

The management skills gap

As

And management skills are really an entirely different domain than sales, empathy or technical competency skills. In fact, given the self-selection of most experienced advisers — individuals who, by necessity, were sales people first and foremost — management skills now arguably represent the biggest skills gap for most firms today.

Accordingly, demand for COO positions in advisory firms over the past six years has driven a

The 4 skill domains of advisers

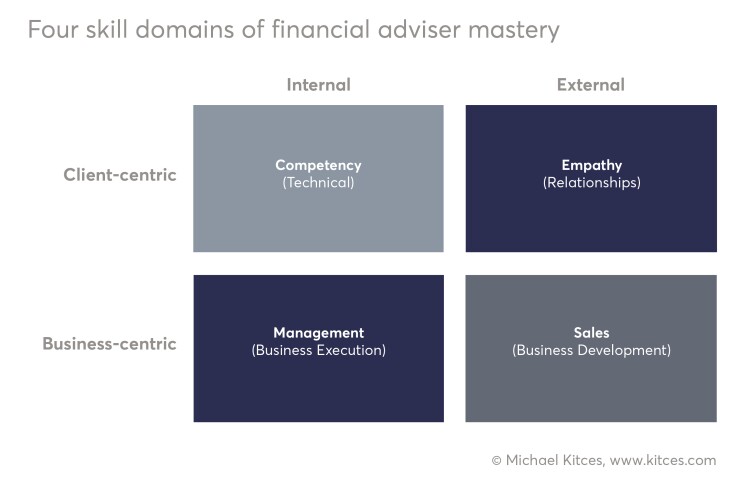

Given these dynamics, there are ultimately four domains in which advisers may seek to improve their skills to advance their careers: competency (technical), empathy (relationships), sales (business development) and management (business execution).

Notably, there is a significant difference in the focal areas of each skills domain. Developing the adviser’s competency and empathy are ultimately client-centric skillsets. By contrast, the domains of sales and management are more outward-facing and business-centric. Viewed another way, competency and empathy are about working in the business, while sales and management are about working on the business.

In theory, advisers who are naturally

More generally, given most people have a natural inclination toward one domain or another, most advisers will struggle to master all four. Instead, advisers will typically start out with an innate skillset for one (a natural aptitude for sales, or technical competency), expand into a second to advance their career (improve sales or empathy/communication skills or advance their technical competency), and a few may cross over to a third in the later stages of their career (e.g., moving from traditional advising into managing an advisory firm, or someone in a management position who decides to shift into a client-facing advisory position). Those who master all four will be relatively few, but those are also the ones who will likely rise to the top of the largest and most successful firms.

Charting a course to advancement

As advisory firms grow, the roles within firms are becoming more specialized. The benefit of this shift is that it provides an opportunity for advisers (and all employees) to move into the role that is best suited to their natural talents. The challenge is that it may make them so comfortable that they never learn to improve their skillsets in other domains — which, ultimately, will limit their upside.

In fact, viewed from the opposite direction, it’s the expansion of mastery into other skillsets that increasingly defines the advisory career track itself. It starts with

Adding new domains of mastery is key to progressing down the adviser career track. That it’s so difficult to develop proficiency in so many areas is perhaps why, in the end, fewer advisers are ultimately becoming partners/owners of advisory firms.

For firms looking to develop talent, they would do well to consider how they might help develop their employees’ proficiency in each of these domains. And advisers looking to advance their own careers should recognize that if they