Now with more than $2 trillion in assets, ETFs have become hugely popular — yet, ironically, the ability to trade them intraday has become a liability, with market volatility triggering a number of extreme situations in which ETFs have briefly traded at significant discounts to their NAV — in some cases, as much as 30%.

This may be of small consequence for buy-and-hold clients and their advisors, who did not trade during the recent price swings. But it highlights that, when ETFs experience bouts of illiquidity, they can trade at steep discounts. And this can be disconcerting for clients who need to trade during such market volatility — especially when they have a trade unwittingly triggered by the ill-advised use of a stop-loss market order.

LIMIT ORDERS

At a minimum, those who make use of stop-loss orders as a form of risk management may want to consider using stop-loss limit orders instead. While the stop-loss trade will still be triggered when the stock price declines to a certain level, the corresponding use of a limit order — set at a small gap below the stop-loss threshold — ensures that a sale is not triggered at the nadir of a

While mutual fund buyers and sellers don’t need to worry about whether a trade will be executed at the representative price tied to the underlying shares, ETF owners do. The funds are technically traded as a wrapper around the underlying securities, meaning the price can differ from the NAV.

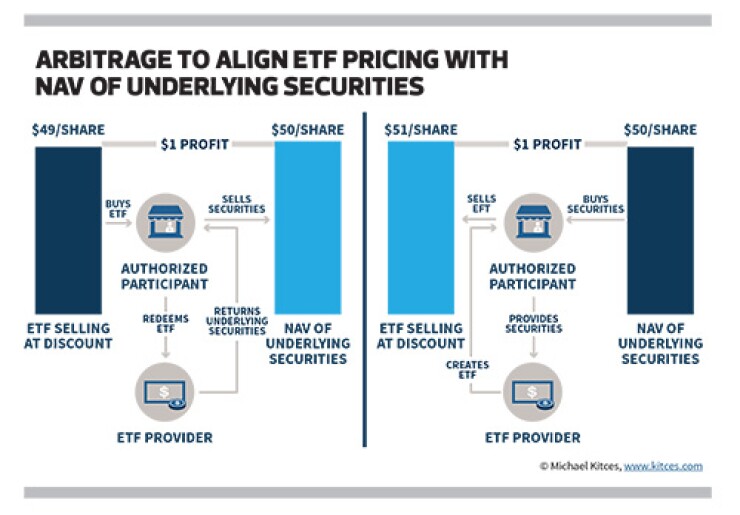

ETF ARBITRAGE

In practice,

If an ETF is valued at a material premium above its NAV, an arbitrageur can buy all the underlying stocks, exchange them with an authorized participant to create a share of the ETF and then sell the ETF for an immediate profit.

Conversely, if the ETF is priced at a discount, the arbitrageur would buy the ETF, redeem it with an authorized participant and immediately sell the underlying stocks to earn a profit.

ILLIQUID MARKETS

A crucial caveat is that the arbitrage process works only if both the ETF and the underlying securities are liquid. Buying the ETF at a discount in order to redeem and sell the underlying securities isn’t risk-free arbitrage if the underlying securities can’t be sold. Instead, the prospective arbitrageur would have to sit on them for an unknown period of time (or vice versa by buying the stocks to create an ETF but then being unable to sell the ETF itself).

The critical point is that, over the long run, ETFs are only as liquid as their underlying securities, since the

In addition, because liquidity most commonly vanishes during times of market distress, the resulting lack of transparent pricing around the ETF and the ongoing selling pressure is highly likely to result in a downward gap — that is, the ETF will trade at a potentially significant discount to its NAV.

In recent months, a number of organizations,

Unfortunately, the ETF volatility on Aug. 24 proved the point. On that day, for short periods of time, certain ETFs traded at dramatic discounts.

The

That same day, the

For most investors, avoiding unfavorable ETF trades when the market is volatile is pretty straightforward: Just don’t trade. The price distortions that occurred corrected themselves in a matter of hours, once the arbitrageurs were able to begin the normal process of helping the ETF price converge on its underlying NAV.

But advisors who used stop-loss orders to limit their clients’ risk encountered a bigger problem. Unless specified otherwise, a stop-loss order becomes a market order once the stop-price threshold is triggered, which meant some advisors found themselves executing orders to sell at the market’s open.

STOP-LOSS MARKET ORDERS

In a normal environment, stop-loss orders aren’t necessarily a problem.

Imagine an advisor whose clients own shares of an ETF trading at $55 per share. To protect the investment, the advisor enters stop-loss orders at $50 per share. When ETF prices decline in a continuous series of one-cent increments, the stock is simply sold as soon as the $50 threshold is reached, likely at a price of $49.99.

However, when the price of a security gaps downward and an ETF crash occurs, there may be a different outcome. If the previous closing price was $51, and the investment opens the next morning around 10% lower, a stop-loss market order will result in a sale at the $46 opening price, even if that price is in effect for only a few seconds until the arbitrageurs correct it. That is exactly what happened to some investors on Aug. 24.

STOP-LOSS LIMIT ORDERS

The solution to this dilemma is for advisors to use a stop- loss limit order, with the limit order price set slightly lower than the stop-loss threshold.

For instance, instead of placing a stop-loss (market) order for $50, the advisor might place a stop-loss limit order with the stop set at $50 but the limit order at $48.

This way, if the ETF falls slowly, the order will still be executed just below $50, but if the ETF price crashes, the order won’t be triggered until the ETF recovers above $48, avoiding a badly timed sale during ETF illiquidity.

When it comes to dealing with individual stocks, there has always been an issue between balancing the risk of using a stop-loss market order and a stop-limit order, where if the stock gaps down and keeps falling, the trade might not be executed, ever, and the investor could ride the stock all the way down. But using stop-loss orders with ETFs is fundamentally different from stocks, since a stock can lose all of its value and sink to zero, which is virtually impossible for a diversified basket of stocks.

BEST PRACTICES

The implication is that advisors and investors who might have been wary of using stop-limit orders for stocks should still consider them as a best practice for their ETFs.

How wide should the gap be between the stop-loss threshold and the underlying limit order? While there’s no clear rule on this, it has been rare for an index to gap down more than 10%, suggesting that a 10% gap might be reasonable. Advisors who want tighter thresholds, or perhaps are more optimistic that a sharp sell-off will be met by a sharp bounce, might set a limit-order target at just 5% below the stop-loss threshold.

The goal is to create a stop-limit gap that is wide enough so that, if an ETF declines gradually, the limit order will still trigger.

If the price of the ETF drops precipitously, however, the trade won’t execute until the price rebounds. Of course, for advisors and their clients who trade actively, managing risk through stop-loss orders may be unappealing.

But for those who do use stop-loss orders, a stop-loss limit order to guard against a badly timed execution seems advisable. For those who are truly long-term investors and don’t need to sell in a market downdraft, ETF price plunges may be an opportunity to buy at a deep discount.

Read more: