Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

On Jan. 22, the CDC received

Unfortunately, this only begins to tell the tale of how one of the worst pandemics in U.S. history has impacted Americans. In addition to the tragic loss of life, the COVID-19 pandemic has also wreaked havoc on the U.S. economy.

As incredible as that 20-million figure is, it could have been even worse. Notably, on March 27, the

These PPP loans were instrumental in helping many small business owners not only survive the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic but also preserve jobs for their employees. The loans came with minimal underwriting, an interest rate of just 1%, and a maturity period of between two and five years (loans funded on or after June 5, have maturities of five years while loans funded prior to June 5, have maturities of two years, unless the borrower and the lender mutually agree upon an extension).

But while the loans’ terms were attractive, the cherry on top — the big benefit to business owners that was meant to entice them enough to take the loan in the first place — was undoubtedly the ability to have some (or potentially all) of the loan forgiven, which would effectively turn the loan into a grant of ‘free’ money instead.

However, the forgiveness of PPP loans is not automatic. Instead, in many instances, the choices and decisions that business owners make now, even months after receiving the loan, can play a significant role in how much of their loan will be forgiven. Accordingly, advisors should have an understanding of the PPP loan forgiveness rules, so that they can help guide small business owners through the process.

Paycheck protection program at a glance

The PPP was an unprecedented effort to get money into the hands of small business owners at breakneck speed, which is no small feat given the incredibly large quantity of small businesses in existence across the country. To do so, the PPP relied upon banks, credit unions, and other approved lenders to underwrite and process the loans, which would be fully backed by the SBA (to eliminate the risk to those lenders in lending money to potentially-in-crisis small business borrowers). To that end, from the beginning of April, through the program’s close (at least for purposes of issuing new PPP loans) on Aug. 8, some 5,460 different lenders facilitated a whopping 5,212,128 loans.

Incredibly,

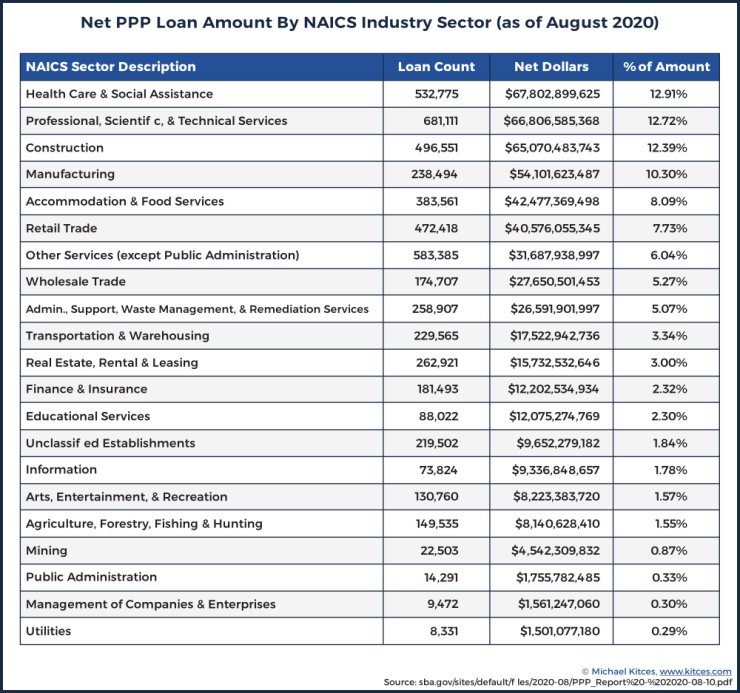

Ultimately, the additional funding proved to be more than enough. As of the program’s close date on Aug. 8, some $525 billion of loans had been approved to nearly every kind of business (see chart below) through the PPP program (meaning, in the end, $134 billion of the $349 + $310 = $659 billion that had been allocated to the program went unused).

The vast majority of the loans issued under the PPP were relatively small. In fact, as the chart below illustrates, of the roughly 5.2 million loans issued, nearly 70% were for loans of $50,000 or less. It’s worth noting, however, that despite their prevalence, such loans only accounted for 12% of the total value of all loans issued (as a high volume of a lot of very small loans still only adds up to a relatively small amount). By contrast, loans between $5 million and $10 million (the maximum amount available under the PPP) represented just 0.1% of all loans issued but accounted for 6.3% of all PPP funds.

CALCULATING THE MAXIMUM AMOUNT OF A PPP LOAN

PPP loans were available to businesses, provided the business met two requirements. First, it had to be considered a “small business,” which was generally defined as those with less than 500 employees (certain businesses in industries where the

Provided a business met these two conditions, it was eligible to receive a PPP loan equal to the lesser of 2.5 times their average “eligible monthly payroll” costs, or $10 million.

Eligible monthly payroll costs included salaries and wages for employees, and profit for sole proprietors and partners (each of which were subject to a maximum annual amount of $100,000 of such salary/wages/income that could be considered), as well as payments made for employees’ group health benefits, retirement contributions, and state and local taxes.

For purposes of determining the business’ average monthly payroll, businesses generally used the average monthly payroll for 2019. Seasonal businesses, however, were able to use average monthly payroll between Feb. 15, 2019, and June 30, 2019, or any 12-week period between May 1, 2019, and Sept.15, 2019. On the other hand, new businesses (i.e., those that didn’t have such historical payroll numbers because it wasn’t in operation yet in 2019) were able to use their average monthly payroll from Jan. 1, 2020, to Feb. 29, 2020.

Example 1: In 2019, The Duchess Sporting Goods Company had two employees, each of whom earned a $50,000 salary. Duchess Sporting Goods also contributed a total of $30,000 towards health benefits and $10,000 to 401(k) accounts for both employees.

Accordingly, the maximum PPP loan Duchess Sporting Goods would have been able to receive would be 2.5 times its average eligible monthly payroll costs, or (($50,000 + $50,000 + $30,000 + $10,000) ÷ 12) x 2.5 = $29,167.

WHAT COULD PPP LOAN PROCEEDS BE SPENT ON?

For many small business owners, the PPP was a lifeline that prevented them from reducing employee headcount or compensation any further, or in some cases, shutting the business down altogether. But while PPP loans provided business owners with much-needed liquidity, they did come with some strings attached.

More specifically, the CARES Act limited the use of PPP proceeds, requiring at least 60% of the proceeds to be used for payroll costs, and the remaining proceeds (no more than 40%) available for additional expenses that included rent, mortgage interest, utilities, and other business interest on debt incurred prior to Feb. 15.

Breaking down the PPP loan forgiveness formula

As noted earlier, PPP loans were issued with 1% interest rates and maturities of either two or five years. For struggling businesses, those are pretty favorable terms. Heck, for any business, those are pretty favorable terms.

But while some businesses intend to pay back their PPP loans (or have already paid them back), the overwhelming majority of business owners who sought PPP loans did so with the intention of having as much of the loan forgiven as possible.

On the surface, the formula for determining how much of a PPP loan will be forgiven is fairly straightforward, as illustrated in the graphic below. Like many rules and regulations, however, the ‘devil is in the details’, and some legwork may be required to determine the necessary information for the calculation, including the covered period to report, the eligible expenses to claim, the wage reductions applied, and the number of FTEs maintained.

UNDERSTANDING THE COVERED PERIOD OF A PPP LOAN

The covered period of a PPP loan is the period of time during which expenses eligible for forgiveness are “incurred” or for which there are “payments made” (more on this in a moment), that can count towards the forgiveness calculation.

For loans funded on or after June 5, the covered period is the 24 weeks that follow the receipt of the loan proceeds (i.e., they have/had to be ‘used’ on eligible expenses in the 24 weeks after they’re received, in order to be eligible for forgiveness). By contrast, loans that were funded prior to June 5, originally had only eight weeks in their covered period but were subsequently amended to give borrowers the discretion to choose either eight weeks or 24 weeks.

Fortunately, though, the overwhelming majority of PPP loans were funded prior to June 5, and thus, the overwhelming majority of borrowers have the flexibility of choosing either an eight-week or the longer 24-week (if necessary) covered period.

THE ALTERNATIVE PAYROLL COVERED PERIOD PPP LOAN

In addition to the standard covered period, the SBA and Treasury rules also provided an option for employers to use an alternative payroll covered period. The alternative payroll covered period is, at a high level, exactly what it sounds like; another covered period that can be elected by some business owners that only applies to payroll expenses (other expenses are still subject to the ‘regular’ covered period).

The alternative payroll covered period begins on the first day of the start of the next payroll period, after the PPP has been funded (instead of when a borrower received their PPP funding), and runs for eight or 24 weeks (the same length of time as the business owner chose/was required to use for the ‘regular’ covered period).

It’s important to note, though, that not all businesses can utilize this additional covered period. Rather, to do so, a business must run their payroll on a bi-weekly (or more frequent) basis.

The primary benefit of using the alternative payroll covered period (when eligible) is to allow for more payroll costs to count towards forgiveness. Since many businesses actually pay their employees at some point after the end of a payroll period, using the alternative covered payroll period can allow that business to get the total amount of a previous payroll schedule’s costs included in its alternative covered payroll period.

Example 2: Mock Turtleneck Winterwear, Inc. received a PPP loan on Mon., May 4. Mock Turtleneck pays its employees every other Wednesday for work performed during the previous two weeks. At the time of the receipt of its PPP funds, the company was 1 week into its current payroll cycle. Accordingly, its next pay date was May 13, at which point it would pay its employees for work performed during the weeks of April 27 and May 4.

Using a ‘regular’ eight-week covered period, Mock Turtleneck would be able to use payroll costs incurred or paid from the week of May 4, through the week of June 22, towards its forgiveness calculations. Accordingly, as the graphic below illustrates, despite an eight-week covered period, Mock Turtleneck would actually be able to use the payroll costs from nine weeks (covering the payroll expenses for work performed between April 27 and June 28) towards its forgiveness calculations.

Not bad!

But it could be even better with the election of the alternative covered payroll period.

More specifically, by virtue of its biweekly pay schedule, Mock Turtleneck qualifies to elect the alternative covered payroll period. And by doing so, the alternative covered payroll period (for payroll expenses only) begins on May 11 (because it was the first day of the new pay cycle — running May 11-24 and paid out on May 27 — after receiving the PPP loan on May 4).

The effect of this change, as can be seen in the graphic above, is by virtue of paying the previous payroll period’s costs during the alternative covered payroll period, they are eligible to count towards the expenses used to qualify for PPP forgiveness. Plus, the additional eight weeks of payroll costs incurred during the alternative covered payroll period (and paid afterward at the next scheduled pay date) will also count toward the forgivable amount.

Thus, by using the alternative covered payroll period, 10 weeks’ worth of payroll expenses can be used, instead of ‘just’ nine.

Using the alternative covered payroll period comes with the added complexity of having to keep track of two separate covered periods (because only payroll expenses apply to the alternate covered payroll period — PPP funds used for all other expenses must be tracked with the standard covered period), but for some businesses, the added flexibility and additional payroll expenses that can be included in the forgiveness calculation will make that added complexity worth it.

However, for other businesses that spend enough on payroll costs during the ‘regular’ covered period to get the maximum potential forgiveness, the election of the alternative covered payroll period adds unnecessary complexity and should not be used.

ELIGIBLE EXPENSES FOR PPP LOAN FORGIVENESS ARE INCURRED OR PAID

“An eligible recipient shall be eligible for forgiveness of indebtedness on a covered loan in an amount equal to the sum of the following costs incurred and payments made during the covered period [emphasis added]:

- Payroll costs

- Any payment of interest on any covered mortgage obligation (which shall not include any prepayment of or payment of principal on a covered mortgage obligation)

- Any payment on any covered rent obligation

- Any covered utility payment”

Notably, in subsequent guidance provided by the SBA and Treasury, a provision was adopted for the forgiveness calculation similar to the provision adopted for how PPP loan proceeds could be used in general. Thus, at least 60% of the amount of the PPP loan proceeds that are forgiven must be spent on payroll costs, limiting the amount forgiven spent on rent, mortgage interest, or utilities to 40%.

Of course, for businesses who simply use 100% of their proceeds on payroll costs, this is a moot point, but for borrowers that cannot fully use their proceeds for payroll costs alone during the covered period — which is more likely to be the case when an eight-week covered period is used, because the amount of the loan was based on 2.5 month’s, or roughly 10 weeks, of payroll costs — the minimum requirement of how much in PPP loan proceeds must be spent on payroll costs becomes important.

Example 3: Mad Milliner Productions, LLC received a PPP loan of $200,000. During the covered period, Mad Milliner spent $80,000 on payroll expenses and another $80,000 on other (eligible-but-not-payroll) expenses.

Here, although $80,000 (50% on payroll) + $80,000 (50% on non-payroll) = $160,000 of PPP funds were spent on eligible expenses during the covered period, the full $160,000 will not be forgivable. The 50% of non-payroll expenses exceeds the allowable 40% maximum forgiveness limit.

Therefore, a reduction must occur, and only $53,333 spent on non-payroll expenses will be eligible for forgiveness, such that the total amount of Mad Milliner’s PPP loan forgiven is $53,333 (non-payroll expenses) + $80,000 (payroll expenses) = $133,333 and 40% of the $133,333 forgiveness amount is $53,333 (of non-payroll expenses).

Paid andincurred costs allowed for eligible expenses during the covered period of a PPP loan give businesses flexibility around the accounting systems they use

It’s also important to note the somewhat unusual language Congress chose to use when determining how much of a PPP loan would be forgiven; “the sum of the following costs incurred and payments made.” Notably, there is no “incurred or paid” method of accounting; usually, expenses are counted using either the cash-basis method of accounting, which looks at when dollars are actually spent, or the accrual-basis method of accounting, which looks at when the action that created the expense actually occurred. Thus, initially, it was unclear what the rule was going to be. Were business owners going to be able to choose between the two?

In the end, the SBA and Treasury adopted the super-business-owner-friendly construct of essentially allowing both methods of accounting to be used … simultaneously. Stated differently, PPP funds used to pay for eligible expenses can be forgiven as long as they are either actually paid during the covered period or incurred during the covered period.

There is one small but critical issue that business owners need to be aware of to utilize this (incredibly favorable) treatment of expenses. In order for expenses that are incurred during the covered period to count towards the forgiveness formula, they must be paid on or before the next scheduled pay date/billing date. If an expense is not paid during the covered period, or is incurred but not paid by the first regular billing date thereafter, it will not be eligible as a paid or incurred expense.

Example 4: Harte’s Knave Casino Group, LLC received a PPP loan and had an eight-week covered period. The company operates a substantial amount of electronic machinery and has monthly electricity bills of $4,000 per month.

Suppose that on Day 1 of the covered period, Harte’s Knave sent a check for $4,000 to pay an existing electricity bill that had been invoiced. That $4,000 would be eligible to be used when determining the amount of the company’s forgiveness because payment was made during the covered period (even though the expenses were incurred before the start of the covered period).

One month later, the company pays another $4,000 electricity bill, which is once again an eligible expense (the expense was both paid for and incurred during the covered period).

Suppose now that, after paying the second electricity bill of $4,000, there are still 26 days left in the covered period. Harte’s Knave won’t pay the bill for the electricity used during those days until after the covered period is over. However, as long as they pay the bill on or before the next regular pay date, they would be able to include the additional expenses incurred during the covered period (but not the expenses incurred outside the covered period) as part of the forgiveness calculation.

That would be another 26 days of electricity use during the covered period for a total of 26 days (period of expense incurred during covered period) ÷ 30 days (period of total expense incurred) x $4,000 (total electricity bill) = $3,467 eligible for forgiveness.

In essence, by utilizing the ‘paid or incurred’ oddity of accounting, Harte’s Knave is able to use nearly three months of electricity expenses in calculating their forgivable amount, even though the covered period was less than two months (just eight weeks).

ELIGIBLE PAYROLL COSTS AS DEFINED BY THE PPP ARE DECEIVINGLY COMPLEX, ESPECIALLY FOR BUSINESS OWNERS

The PPP was primarily designed as a way to help keep workers employed (or, as one might say, to protect workers’ paychecks). Accordingly, there are a significant number of rules (such as the 60% minimum spend requirement and minimum forgiveness threshold that applies to payroll expenses) designed to ensure that a substantial portion of the PPP funding allocated by Congress went directly to workers as “payroll.”

But while the word “payroll” is likely to invoke the idea of “wages” or “salary”, the term “Payroll Costs”, for purposes of PPP loans, is decidedly broader. For instance, in addition to including net earnings from self-employment (for those who are paying themselves as business owners.) along with wages, commissions, salary, and other cash compensation (capped at an annualized $100,000 per employee), Payroll Costs also generally include:

- Vacation, parental, family, medical and sick leave payments;

- Group health coverage (including insurance premiums);

- Retirement benefits; and

- State and local taxes

However, while these expenses can generally be included in the amount of a PPP loan eligible for forgiveness, and self-employed individuals can even include some of their own earnings from the business as payroll (even if not actually received as a W-2 salary, in the case of partnerships or sole proprietorships), the SBA and Treasury rules limit the ability to include some of these other ‘employee benefits’ payroll-related expenditures if they are made on behalf of business owners themselves (who work at/for the company).

More specifically, the following expenses arenot considered payroll costs:

Group health coverages, to the extent that costs are for:

- S corporation owner-employees with 2% or more ownership, or their family members;

- Schedule C/F businesses; or

- General partners

Retirement benefits, to the extent that costs are for:

- An owner-employee of a C corporation or an S corporation (excluded only when costs exceed 2.5 ÷ 12 = 20.8% of the 2019 contribution made by the employer);

- Schedule C/F businesses;

- General partners

State and local taxes, to the extent that they are attributable to:

- Schedule C/F businesses; or

- General partners

REDUCTIONS IN LOAN FORGIVENESS FOR NOT MAINTAINING HEADCOUNT OR SUFFICIENT COMPENSATION

As noted earlier, the primary purpose of the PPP was to safeguard the employment status of small business workers. Accordingly, some businesses that received PPP loans, but that failed to adequately protect worker’s compensation, may be ‘punished’ via a reduction in the amount of their PPP loan that is eligible to be forgiven.

Or at least some of them are …

As while the PPP did originally include requirements for businesses to maintain certain employee headcount requirements to be eligible for forgiveness on their PPP loans, on Oct. 8, the SBA and Treasury announced that borrowers who received loans of $50,000 or less wouldnotbe subject to such reductions in forgiveness. Which, notably, ‘covers’ more than two-thirds of PPP borrowers (but only about 10% of loan dollars). However, borrowers who took larger loans must still deal with a variety of rules that can result in a reduction of the forgivable amount of their loan.

More specifically, reductions in the forgiveness of PPP loan proceeds spent on eligible expenses during the covered period are generally applied for both reductions in the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) employees (the number of cumulative 40-hour workweeks a business’ employees perform) during the covered period (as compared to a reference period)and reductions in (non-highly-compensated) workers’ compensation in excess of 25% (to prevent businesses from claiming they maintained headcount but then drastically cutting compensation for all the employees they kept on payroll). In other words, businesses had to maintain at least the same number of full-time equivalent employees at the start and end of the covered period, and those (non-highly-compensated) employees had to maintain at least 75% of their compensation (i.e., a not-more-than-25% reduction in compensation) to remain fully eligible for PPP forgiveness.

There are, however, a variety of exceptions to the required thresholds of which business owners should be made aware.

Determining how reductions to FTE employee headcount will reduce PPP loan forgiveness

Some businesses that received PPP loans were able to maintain their employee headcounts and hours throughout their covered periods. In such instances, the reward that those businesses receive is the ability to completely ignore this part of the forgiveness process.

Of course, not all businesses — even with a boost from the PPP — were able to maintain employee headcount. The penalty for not doing so is a reduction in the amount of the business’ PPP loan that would otherwise be forgiven (with some exceptions, discussed later).

More specifically, a business must compare its average weekly FTE Employees during the covered period (or, if elected, the alternative payroll covered period) to its FTEs during either the period from Jan. 1, 2020 – Feb. 29, 2020, or during the period from Feb. 15, 2019 – June 30, 2019. Notably, businesses can pick the more favorable of these periods (the period in which there were fewer FTEs) for the comparison.

In general, to compare the number of average weekly FTEs during the covered period and the comparison period, it is necessary to determine the average weekly FTEs during both periods. A standard FTE is equivalent to one 40-hour workweek, regardless of the number of individuals it takes to get to the 40-hour mark. Thus, a single worker who works 40 hours in a single week is equivalent to one FTE for that week. Similarly, if two workers each work 20 hours in a week, they would also constitute, together, a single FTE, as would eight workers each working five hours per week, and so on.

One caveat to this rule, however, is that a single worker cannot comprise more than 1 FTE per week, even if that individual works for more than 40 hours during the week. Thus, while two workers who each work 30 hours per week will constitute (30 x 2) ÷ 40 = 1.5 FTEs, a single individual working 60 hours in a week will be equal to just 1 FTE.

Once the numbers of average weekly FTEs during the covered period and the comparison period are known, the two amounts must be compared. And, in general, any decrease in the number of average weekly FTEs from the comparison period to the covered period will result in a reduction of the forgivable amount of the PPP loan.

For borrowers that do fail to maintain their FTE headcount, the adjustment to their PPP forgiveness is relatively straightforward: the otherwise forgivable amount of the PPP loan will be reduced by the same percentage as the percentage drop in FTEs from the comparison period to the covered period. So, for instance, a 20% drop in average weekly FTEs from the comparison period to the covered period will typically result in a 20% decrease in the amount of the PPP loan a business received that would otherwise be forgiven.

Example 5: March Hare Tea Company, LLC received a PPP loan of $100,000. During its eight-week covered period, March Hare expended $100,000 on expenses eligible to be included in the PPP loan forgiveness calculation (including spending at least 60% on payroll costs). Thus, it is eligible to have up to its full $100,000 PPP loan forgiven.

During both potential comparison periods, Jan. 1, 2020 – Feb. 29, 2020 and Feb. 15, 2019 – June 30, 2019, March Hare employed three individuals, who each worked 40 hours or more per week every week. Accordingly, March Hare’s average weekly FTEs for comparison purposes is three.

Suppose, though, that during the beginning of its covered period, March Hare was not operating at full capacity, and thus, it did not maintain the same level of average weekly FTEs, as shown in the chart below. As the chart shows, during its eight-week covered period, March Hare only maintained an average of 1.875 FTEs per week.

March Hare’s 1.875 FTEs during the covered period represented 3 – 1.875 = 1.125 fewer average weekly FTEs than it had during its comparison period, or a 1.125 ÷ 3 = 37.5% drop in FTEs.

Accordingly, the forgivable amount of March Hare’s $100,000 PPP loan will be reduced by 37.5% x $100,000 = $37,500, which they will have to repay, while the remaining $100,000 – $37,500 = $62,500 can be forgiven.

Safe harbor FTE calculation

Incredibly enough, there is yet another election that business owners can choose to make when calculating whether they maintained employee headcount and/or the amount by which their headcount (and thus their forgivable PPP loan) was/is reduced.

Instead of using actual hours worked to calculate FTEs, the business can opt to use a safe harbor method, where all employees who work 40 hours or more during a week are counted as 1 FTE, while all employees who work less than 40 hours during a week are counted as one-half of an FTE.

Perhaps not surprisingly, this is an all-or-nothing decision. A business can’t, for instance, use the safe harbor in some weeks, but not others. Or for some employees, but not others. It’s either used for all the employees for every week of the covered period or for none of the employees in any week of the covered period.

Using the safe harbor method to calculate FTEs will usually alter the number of FTEs for comparison purposes.

Example 6: Recall March Hare Tea Company, LLC, from the prior example, who took a PPP loan of $100,000 and calculated FTEs during the covered period of 1.875, versus three FTEs during their comparison period. Accordingly, the forgivable amount of their PPP loan was reduced by 37.5%.

Suppose, however, that instead of using the standard method of calculating its FTEs, March Hare chose to use the safe harbor method.

As illustrated in the chart below, March Hare would actually end up with fewer FTEs than was calculated using the ‘regular’ method.

Instead of 1.875 FTEs, using the safe harbor method to calculate FTEs results in a calculation of 1.8125 average weekly FTEs during the covered period.

Therefore, using this safe harbor method would not be advisable for March Hare, as it would result in a lower average weekly FTE value of 1.8125 (versus 1.875 using the standard method) than it had during its comparison period, or a (3 – 1.8125) ÷ 3 = 39.58% drop in FTEs.

Accordingly, the forgivable amount of March Hare’s PPP loan will be reduced by 39.58% x $100,000 = $39,580, instead of by only the $37,500 reduction shown in Example 5, which would have applied if the regular method of calculating FTEs was used.

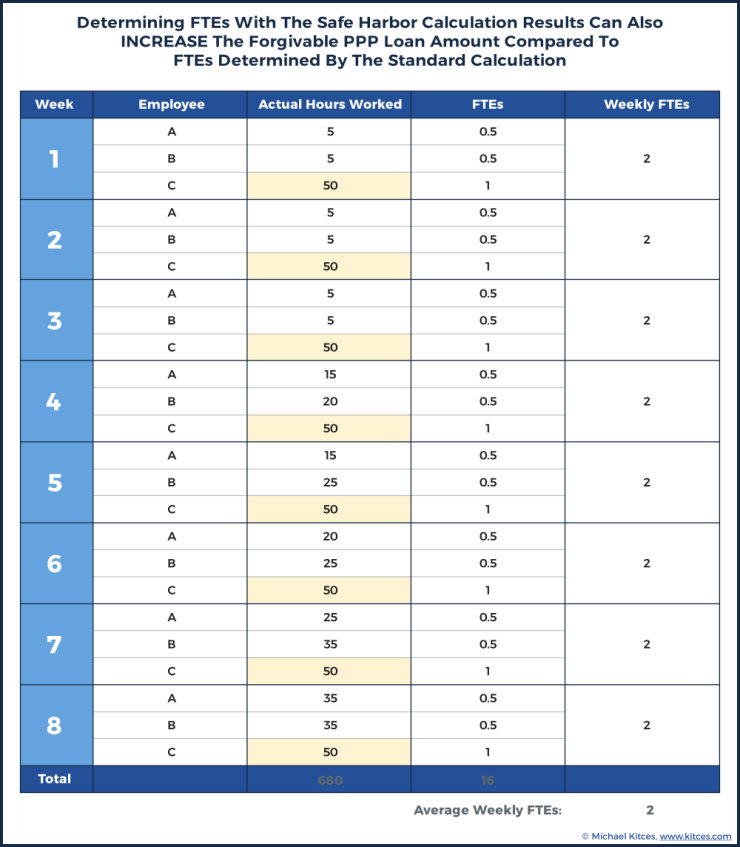

It’s important to note, though, that while using the safe harbor method of calculating FTEs would have resulted in a negative outcome in the example above, its use can actually result in either a positive or a negative effect on forgiveness, depending on the specific set of facts and circumstances.

Example 7: Suppose that March Hare Tea Company, LLC (from Examples 5 and 6) adjusted some of Employee A and Employee B’s hours, such that the total number of hours worked between them was the same, but in a way that would allow them to increase the number of FTEs they’d be able to claim during their covered period.

Accordingly, by using the actual hours method of calculating FTEs, March Hare Tea Company’s FTEs during the covered period would be the same 1.875 FTEs as calculated in Example 5.

If, however, those hours were distributed between Employees A and B as illustrated in the chart below, such that they each contribute 0.5 FTE, then unlike the result in Example 6, using the safe harbor method would not only be simpler but would also result in a more favorable forgiveness calculation.

More specifically, March Hare would count two FTEs during its covered period instead of 1.875.

Accordingly, the forgivable amount of March Hare’s PPP loan would be reduced by (3 – 2) ÷ 3 = 33.33% x $100,000 = $33,333, instead of by the $37,500 reduction shown in Example 5, which would have applied if the regular method of calculating FTEs was used.

Exceptions to reductions in loan forgiveness due to a drop in FTEs

Although Congress was intent on making sure that PPP loan proceeds were used to keep workers employed through at least the end of the covered period, it recognized that there would be some situations where doing so would not be possible, for reasons largely (if not entirely) outside of an employer’s control. In particular, some business owners with lower-wage employees raised concerns that the enhanced unemployment benefits made available as a part of the CARES Act were

Accordingly, Congress, the SBA, and Treasury, collectively crafted a series of exceptions to the general rule for reductions in forgiveness. Thus, a business will not have its forgiveness amount decreased for any of the following situations occurring during the covered period or alternative covered period:

- The borrower made a good-faith, written offer to rehire an individual that was rejected by the employee;

- The employee was fired for cause;

- The employee voluntarily resigned;

- The employee voluntarily requested and received a reduction in their hours;

- The borrower made a good-faith effort to restore any reduction in hours at the same pay, but was rejected; or

- The borrower tried but was unable to hire similarly qualified employees for unfilled positions by Dec. 31.

- A careful reading of the above exceptions reveals that they arenot blanket exemptions for an employer that coversevery employee. Rather, they are acceptable ‘excuses’ to ignore a drop in FTE count specific to anindividual employee.

By contrast, there are two additional exceptions to a drop in FTEs that can be used broadly, across a business, forall employees. They are when either:

- The borrower is

able to document an inability to return to the same level of business activity as such business was operating at before February 15, 2020, due to compliance with requirements established or guidance issued by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the Occupational Safety and Health Administration during the period beginning on March 1, 2020, and ending December 31, 2020, related to the maintenance of standards for sanitation, social distancing, or any other worker or customer safety requirement related to COVID–19 ; or - The borrower reduced its number of FTEs between Feb. 15, and April 26, but restored its FTE count by the earlier of Dec. 31, or when its application for forgiveness is submitted.

For certain businesses, these two exceptions to the ‘normal’ FTE reduction rules can be huge. They are effectively ‘get-out-of-jail-free cards’ that will eliminate any and all FTE reductions that would otherwise apply (though PPP funds will still need to be spent on eligible expenses during the covered period to be eligible for forgiveness).

For businesses that are unable to return to the same level of business activity as before Feb. 15, due to compliance requirements, it’s as simple as documenting the public health requirement and the corresponding drop in business activity (read “gross revenue”).

Meanwhile, for businesses that reduced employee headcount or hours at some point between Feb. 15, and April 26, it just needs to reverse those decisions by the end of the year. Thus, now may be a critical time for such businesses to consider bringing back employees, as the difference between rehiring staff on Dec. 15, for example, and Jan. 15, 2021, could be the difference in thousands (or even tens or hundreds of thousands) of additional forgiveness.

Reductions in loan forgiveness for large (greater-than-25%) cuts in compensation to non-highly compensated employees

If not for an additional restriction, shrewd business owners may have looked to avoid drops in headcount by simply cutting employees’ compensation but keeping them employed. However, while certain cuts in compensation are allowed, the CARES Act does limit such actions.

More specifically, to the extent that an employee with annualized salary/wages of less than $100,000 during 2019 has their compensation slashed by more than 25%, the excess (beyond 25%) will result in a dollar-for-dollar drop in the amount of the business’ PPP loan that is forgivable (unlike the reduction due to employee headcount, which is calculated on a percentage basis). This dollar-for-dollar reduction in the PPP forgivable amount due to a reduction in employee compensation is made by comparing the drop in wages/salary during the covered period to the average salary/wages paid to the employee from Jan. 1 – March 31.

However, cuts in compensation of less than 25% to the same employees have no impact on forgiveness. Similarly, cuts to compensation of those earning $100,000 or more in 2019 have no impact.

Example 8: Voice of the Lobster Seafood Deli, Inc. is a small business, which received a PPP loan in May 2020 with an eight-week covered period. The company has three employees: Alice, Bill, and Chessie. In 2019, Alice made $1,000 per week ($52,000 per year), Bill made $1,500 per week ($78,000 per year), and Chessie made $2,000 per week ($104,000 per year). Furthermore, each employee’s salary remained the same in the first quarter of 2020.

As the pandemic picked up steam, Voice of the Lobster announced cuts to payroll, effective April 1, in an effort to avoid terminating any of its employees. To that end, Alice’s salary was reduced from $1,000 per week to $500 per week (50% cut), Bill’s salary was reduced from $1,500 per week to $1,200 per week (20% cut), and Chessie’s salary was reduced from $2,000 per week to $1,200 per week (40% cut).

Here, a reduction in the amount of the business’ PPP loan that is eligible for forgiveness would apply, but only for the cuts made to Alice’s wages, as she is the only employee earning less than $100,000 with a cut greater than 25%.

Note that because Chessie’s annualized wages were more than $100,000 in 2019, cuts made to her wages do not affect the company’s forgivable PPP loan amount. Accordingly, the deli is free to ‘slash’ Chessie’s wages at will, and with impunity … at least as far as cuts to its own PPP loan forgiveness amount is concerned.

Additionally, during the eight-week covered period, Bill (whose salary/wages are less than $100,000 annually) would have made $1,500 x 8 = $12,000 had his wages not been cut. 25% of this amount is $3,000, so as long as Bill’s wages during the Covered Period totaled more than $12,000 – $3,000 = $9,000 (or $9,000 ÷ 8 = $1,125 per week), there would be no reduction. The total income of $1,200 x 8 = $9,600 that Bill actually earned during the covered period is more than this amount, so no reduction applies.

Alice, however, whose annual compensation is less than $100,000, would have made a total of $1,000 x 8 = $8,000 during the eight-week covered period had her salary not been reduced. 25% of this amount is $2,000, so if Alice had made more than $8,000 – $2,000 = $6,000 during the covered period (or $6,000 ÷ 8 = $750 per week), no reduction would have applied.

But since Alice actually made only $500 x 8 = $4,000 during the covered period, $6,000 – $4,000 = $2,000 less than what she would have earned had her salary only been cut by 25%, the amount of the company’s PPP loan that would otherwise be forgivable must be reduced by $2,000.

Two final points are worth mentioning here. First, similar to the ‘exception’ that allows an employer to rehire a terminated individual by Dec. 31 to avoid a reduction in forgiveness due to a drop in headcount, so too can an employer avoid a reduction in loan forgiveness for cutting a non-highly-compensated employee’s compensation in excess of 25% if the salary is restored by the same Dec. 31 deadline.

However, per the instructions for forgiveness published by the SBA and Treasury, this exception only appears to be available if the decision to slash wages/salary was made between Feb. 15, and April 26. (Whereas subsequent reductions in compensation or headcount that were implemented after April 26 can’t be ignored, even if the employees are subsequently re-hired or restored to their prior compensation level.)

Second, a business that both reduced its FTEs and cut non-highly compensated employees’ wages by more than 25% will have two reductions in the amount of its PPP loan that would otherwise be forgivable.

There is, however, an “order of operations” that must be followed. More specifically, the dollar-for-dollar reduction for salary cuts (to non-highly-compensated employees) is applied first, followed by applying the percentage reduction in forgiveness due to a drop in FTEs to the already reduced amount.

Strategies to help maximize PPP loan forgiveness

As is plainly evident, the rules for determining the amount of a business’ PPP loan that can be forgiven by the SBA are complicated (one might even say “obnoxiously” complicated.). That complexity will inevitably lead to some business owners failing to get the maximum possible amount of their PPP loan forgiven or lead to other planning complications.

Advisors can, and should, help clients avoid this fate by taking steps that include the following:

- Choose the covered period wisely – As noted earlier, PPP borrowers who received their loans prior to June 5, have the flexibility of choosing either an eight-week or a 24-week covered period. This covers the majority of borrowers and provides for ample planning opportunities.

Where the borrower maintains their employee headcount and wages through the ‘regular’ eight-week covered period (or qualifies for an exception to forgiveness reductions) and expends enough on payroll (and, if necessary, on other expenses) to have the full PPP loan forgiven (which is pretty likely, if full employment was maintained), the eight-week covered period is the logical option.

If this isn’t enough to get full forgiveness, but the business is otherwise relatively close to the required expenditures to obtain full PPP forgiveness, the next step is to see if the alternative payroll covered period is enough to do the trick.

If the alternative covered period allows the business to spend enough on eligible expenses to get maximum forgiveness, then using it is a ‘simple’ solution.

If it doesn’t, it’s necessary to explore the 24-week covered period option instead. If the borrower maintains headcount and wages through the ‘extended’ 24-week covered period (or qualifies for an exception to forgiveness reductions), then this becomes the logical option.

However, if FTEs are not maintained and/or there are significant (<25%) cuts to the wages of employees with annualized compensation of less than $100,000, further analysis is warranted.

At the heart of the matter lie two questions …

- Does the added time of a 24-week covered period allow the business to spend enough on qualifying expenses, such that including these expenses would more than offset any additional reductions in forgiveness due to a drop in FTEs or cuts to non-highly compensated workers’ wages that might have also occurred during the 24-week period?; and

- Would the added reductions to forgiveness due to declines in FTEs or cuts to non-highly compensated workers’ wages more than offset any gains from the inclusion of additional expenses?

If the answer to question one is “yes” and the answer to question two is “no”, then extending to the 24-week covered period likely makes the most sense. Otherwise, keeping the ‘original’ eight-week Covered Period will probably be more beneficial for the borrower.

Unfortunately, there is no easy way to figure this out. Someone must ‘run the numbers’ using each method and see what the best result is.

Make smart decisions if reductions in FTEs and/or employee compensation are required – There are a lot of ways to try and mitigate the impact of reductions in headcount or payroll for business owners who truly understand the PPP forgiveness rules. Options for business owners who received PPP loans of greater than $50,000 (and thus, subject to the reduction rules) include the following:

- Keep wage cuts to no more than 25% for those employees with annual wages of less than $100,000;

- Where more significant cuts to wages are required, cut the wages of employees with annual wages in excess of $100,000;

- If additional hours are required above 40 hours per week for a particular role, try to hire additional employees (even on a part-time basis) to do the work because their hours will count towards the FTE requirement (while having the original employee work in excess of 40 hours per week won’t add to the FTE count);

- Run FTE calculations using both the ‘regular’ calculation and the safe harbor method; and

- When the safe harbor FTE calculation is used, minimize the number of employees working between 20 and 39 hours per week (no additional credit is received).

More specifically, while

Without such deductions, the profit of some businesses may be ‘artificially’ inflated, leading to higher-than-normal tax bills for business owners.

The last thing anyone wants is an unexpectedly large tax bill. But given the pandemic and the struggles many business owners are already dealing with, that may never be truer than today. Advisors, therefore, must help such clients plan ahead and avoid surprises.

Prepare clients receiving substantial forgiveness for a bigger tax bill – In the event that a business owner is able to successfully navigate the PPP forgiveness rules to have all or a large portion of their PPP loan forgiven, it’s a substantial win for the business owner. But it’s not a total win … at least not yet.

Example 9: Lewis is the sole owner of Wonderland LLC, which typically runs a profit of $150,000 annually. In May, Wonderland received a PPP loan of $400,000. It subsequently spent all the money on eligible expenses and kept all its workforce employed at their previous salary levels.

Suppose, now, that compared to projections of revenue of $3 million and expenses of $2.85 million, the pandemic results in Wonderland’s revenue dropping by $350,000, to $2.65 million, with its expenses only decreasing by $50,000 (in large part because it maintained its payroll expenses) to $2.8 million.

As a result, the company ends the year down a net $350,000 – $50,000 = $300,000 (which results in it going from a net profit of $150,000 to a net loss of $150,000.

If, however, the full PPP loan is forgiven, the $400,000 of expenses that were paid with those funds will no longer be deductible. Accordingly, Wonderland will only be able to deduct $2.8 million – $400,000 = $2.4 million for tax purposes from its $2.65 million revenue. The result is a profit of $2.65 million – $2.4 million = $250,000, which is $100,000 more than Lewis anticipated, even though his business did worse, overall, for the year. Between Federal and state income taxes, this could easily bump his tax bill by $30,000 or more.

Ultimately, that tax bill will be owed, whether Lewis is prepared to pay it or not. But without planning ahead, a $30,000 surprise bill could cause added hardship and angst during a period where there is already plenty of both.

The CARES Act provided a massive stimulus to the American economy in response to the worst pandemic in more than 100 years that gripped the nation. Included in the stimulus was the creation of the much-hyped PPP, which ultimately provided more than half a trillion dollars in loans to business owners in an effort to help them maintain their employee headcount and payroll.

But while the PPP loans, themselves, have been valuable for business owners, the real cherry on top has been the ability to have some, if not all, of the loan forgiven by the SBA. To benefit from this, though, business owners need to navigate a complex web of rules, from understanding various covered periods to knowing what expenses count towards forgiveness — a particularly cumbersome issue for business owners themselves — to dealing with reductions that can apply when employee headcount and/or wages are not maintained throughout the covered period.

The good news for advisors is that this complexity provides ample opportunity to educate clients and to provide invaluable guidance in a time of great need. Doing so not only helps business owners to maximize the amount of PPP forgiveness they receive, but can also create the kind of goodwill that can lead to clients for life.

Jeffrey Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, MSA, a Financial Planning contributing writer, is the lead financial planning nerd at