Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

In December 2017, the Internal Revenue Code underwent dramatic changes, the likes of which had not been seen in more than 30 years. Legislation repealed some parts of the tax code, modified others and created a substantial number of new provisions of the revenue code as well.

Among the newly created provisions of the IRC were Qualified Opportunity Funds, or QOFs. By virtue of their numerous potential tax benefits, QOFs have since received

But while QOFs may present an incredible opportunity for some investors looking to liquidate assets with existing gain, older investors in particular should think twice before selling appreciated assets and reinvesting the proceeds into such funds. That’s simply owed to the fact that QOFs make rather poor estate planning vehicles when compared to other options.

In addition to QOFs,

As defined by

Two additional zones in Puerto Rico

In turn, QOFs are partnerships or corporations created to invest primarily in businesses and tangible property located within QOZs. These funds represent the latest efforts by Congress to encourage growth and development of low-income areas by providing various tax breaks.

TAX BENEFITS

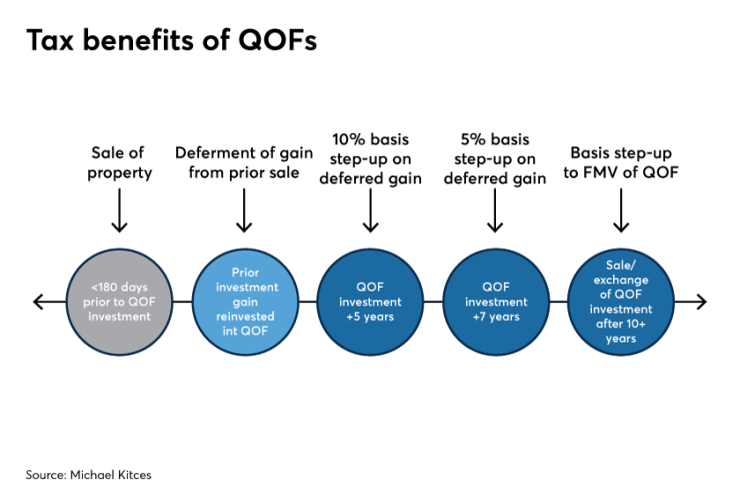

There are three primary tax benefits associated with QOF investments: tax-deferral of an existing gain; basis step-ups of an existing gain; and a tax-free gain of the QOF investment itself. Notably however, these benefits are only available to the extent that gains are reinvested in a timely manner into a QOF.

Under

Example No. 1: On January 26, 2019, Paula sold a building for $2.4 million. At the time her adjusted basis in the building was $1.4 million. In an effort to minimize the tax impact from her sale, Paula reinvested only the $1 million of gain into a QOF on March 31, 2019, and invested the proceeds consisting of her return of basis elsewhere. Since her gain was reinvested within 180 days of the sale, Paula can defer the $1 million gain until December 31, 2026, or until she sells or exchanges the QOF.

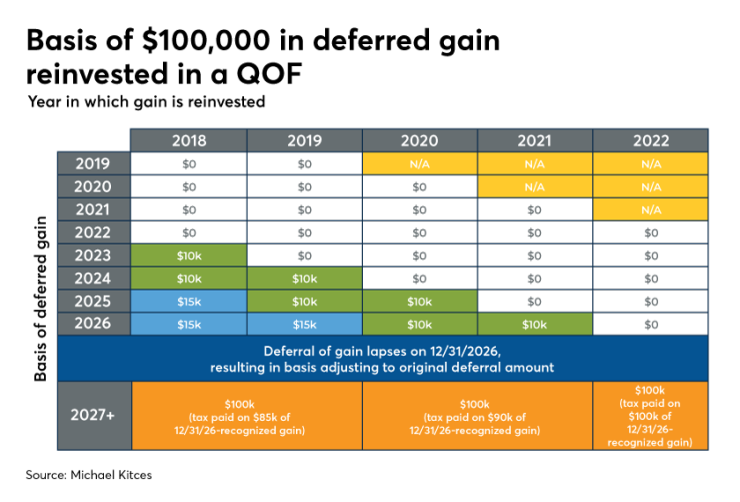

The second major tax benefit afforded to QOF investments made with timely reinvested gain is a series of basis step-ups. More specifically,

Meanwhile, IRC Section 1400Z-2(b)(2)(B)(iv) calls for an additional basis increase of 5% of the still-deferred gain after the QOF has been held for an additional two years, for a total of seven years. Thus, the tax liability on up to a maximum of 15% of the reinvested gain can effectively be erased via the combination of these step-ups.

Example No. 2: On March 31, 2019, the gain that Paula reinvested into the QOF has an initial basis of $0. If she holds the QOF for five years, through March 31, 2024, her basis will increase to $100,000 — that is, 10% of $1 million. If she continues to hold the QOF for an additional two years, through March 31, 2026, her basis will increase to $150,000, or 15% of $1 million.

But there’s a catch. As noted, the step-ups only benefit a reinvested gain that is still deferred. But as also noted, the latest that deferred gain reinvested into a QOF must become taxable is on December 31, 2026 — at least, if the current rules do in fact lapse then. To meet the seven-year requirement needed to get the second step-up of 5%, then, an individual must make their QOF investment by December 31, 2019.

QOF investments made after that date won’t be eligible for the 5% step-up, but investments made between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2021, will still be eligible to receive the 10% step-up after five years. Any gain reinvested into a QOF after that time, though, will not be eligible for any basis increases.

The third and final major tax benefit available when a gain is timely reinvested in a QOF is the potential for all gain-on-gain growth of the QOF itself to be tax-free.

Example No. 3: Paula decides that she will keep her QOF investment, which she purchased on March 31, 2019, until 2030. On December 31, 2026, the deferral of her $1 million gain will lapse, and she will owe tax on $850,000 — that is, $1 million minus $150,000 from the 10% step-up in 2024, and the additional 5% step-up in 2026 — of capital gains. At that point her new adjusted basis will increase to $1 million, the amount of the gain originally deferred.

On January 1, 2030, when Paula plans to sell her QOF investment, she will owe no capital gains tax precisely because since she held the QOF for 10 years, and her basis would adjust on the date of sale to the fair market value of the QOF.

Finally, it’s worth reiterating that perhaps somewhat oddly, each of the above-referenced potential QOF-related tax breaks is only available when the gain from the sale of a prior investment is reinvested in a timely manner into a QOF. By contrast, investments attributable to basis receive none of the same tax benefits. Thankfully though, any basis from the sale generating the to-be-reinvested-in-a-QOF gain

DEATH AND QOFs

While QOFs can offer investors a slew of tax benefits, they aren’t nearly as attractive, from a tax perspective, to beneficiaries.

More specifically, when a beneficiary inherits a

A deferred gain that is reinvested in a QOF is not eligible for a subsequent step-up in basis upon the death of a QOF owner, though. Instead, it becomes

“In the case of a decedent, amounts recognized under this section shall, if not properly includible in the gross income of the decedent, be includible in gross income as provided by section 691.”

As such, if a beneficiary inherits a QOF, the beneficiary will essentially step into the shoes of the original owner with regard to any still-deferred reinvested gain, and will owe income tax on that gain in the same manner as if the owner were still living. Thus, any beneficiary inheriting a QOF prior to December 31, 2026, will at best only be able to retain the deferral on reinvested gain until that date. That’s because the QOF owner would have been required to recognize any still-deferred gain had they lived, but not receive a step-up in basis as the beneficiary would with any other inherited property.

Notably though, it would appear that the beneficiary would get a step-up in basis for any gain attributable to the QOF investment itself — i.e., the gain-on-timely-reinvested-gain — though there is still some uncertainty regarding the issue.

Taken together, these rules don’t make QOFs a poor choice for older investors who must later sell the asset, or who are 100% committed to doing so regardless of the tax consequences for themselves or their heirs. Rather, as discussed in greater depth below, it’s more that in many situations QOFs are just less attractive than other options, at least from a tax perspective, if the QOF is an asset anticipated to be bequeathed to heirs.

Example No. 4: Paula, who reinvested $1 million of gains from a building sale into a QOF on March 31, 2019, died on August 2, 2024. Upon her passing, Connor, Paula’s son, inherited her QOF which, on the date of her death, was fairly valued at $1.15 million — with a $150,000 gain in the $1 million of gains that had been reinvested into the QOF.

Since Paula died after owning her QOF for five (but not seven) years , she would have received a basis increase equal to 10% of her initial investment in the QOF, i.e., $100,000. That basis would be carried over to Connor. And in addition, it seems as though Connor would receive a step-up in basis of $150,000 for the gain of the QOF itself since Paula’s investment. That would bring Connor’s total cost basis to $100,000 + $150,000 = $250,000.

This leaves Connor with $1.15 million — that is, $250,000 = $900,000 of still-deferred gain at the time of his inheritance. If Connor holds the QOF until the seven-year mark counting Paula’s holding period, he will be eligible for an additional $50,000 increase in basis — i.e., 5% of the initial gain timely reinvested — but that’s the best Connor can do.

Connor will consequently have to pay tax on $850,000 of long-term capital gains, even though any other appreciated property Connor might have inherited would have no capital gains at all. And as noted above, that tax bill will arrive no later than December 31, 2026.

Note that beneficiaries of very affluent decedents whose estates were subject to federal estate tax will see the recognized capital gains

INCLUSION EVENTS

Although the lack of a step-up in basis on a reinvested gain is a significant downside of QOFs from an estate planning perspective, the good news at least is that the IRS has proposed that death will not result in previously deferred QOF gains to be included in an investor’s income. In other words, QOF gains can at least carry over to the beneficiary, rather than simply being due at the death of the original owner.

The reason that QOF gain can at least carry over to a beneficiary is that gain reinvested in a timely manner can be deferred until the earlier of December 31, 2026, or when the QOF is sold or exchanged. But in limiting the language in

As is often the case, the IRS was left to fill in these gaps via Treasury regulations, which they did by creating the concept of an inclusion event. This is merely an action that has the effect of treating a QOF as if it were sold or exchanged, thus ending the tax deferral of gain — and triggering any other QOF tax consequences that may apply upon disposition.

In a

Normally, the bequest of a QOF would be a transfer that reduces the decedent’s or the decedent’s estate’s equity interest in a QOF. Nevertheless, under

Specific examples of death-related transactions that are excluded from general inclusion events are a decedent’s QOF transferring to their estate, the estate distributing the QOF to beneficiaries, and a jointly held QOF passing to the other joint owner(s) by operation of law. So while gifting or selling a QOF immediately ends its tax deferral period, bequeathing a QOF to a beneficiary will not. A beneficiary who inherits a QOF will be able to continue deferring taxes on the QOF gain until an inclusion event takes place, such as a sale or exchange, or until December 31, 2026 — whichever comes first.

ILLIQUIDITY

The scenario in Example No. 4 raises an interesting question: What happens if a beneficiary of a QOF investment has limited resources outside of the QOF when December 31, 2026, comes around?” Since that reflects the absolute latest that a gain reinvested in a QOF can remain deferred, a beneficiary who inherits a QOF must have a plan for paying the tax liability on the to-be-recognized amount, even if the QOF itself is not liquid at that time.

And chances are, limited liquidity is going to be the case. By virtue of their very nature of investing into long-term real estate — and often real estate that wasn’t attracting many other investors, thus why it needed QOF tax incentives to get any investment at all — QOFs will typically be highly illiquid investments. Plus, since one of the core three tax benefits of investing in a QOF is the tax-free gain-on-gain growth of the QOF, which is only available after an investor has owned a QOF for 10 years, these investments are generally intended to have lifecycles of a decade or longer.

Example No. 5: Recall Paula from our previous examples, who sold a building for $2.4 million and reinvested her $1 million gain on the sale into a QOF in a timely manner. Her son Connor was the beneficiary of her QOF upon her passing in 2024, and at best is slated to owe long-term capital gains on $850,000 of IRD come December 31, 2026.

Perhaps in addition to the QOF, Connor also inherited $1 million of other, more liquid assets. If so, assuming Connor continues to hold the QOF through December 31, 2026, he can save some or all of those assets to cover the tax bill that will be owed on the forcibly recognized gain.

But what if Paula left her liquid assets to other beneficiaries? Or what if Paula spent through most of her liquid assets during the final years of her life, and there was little other than the QOF to pass on? If Connor isn’t independently wealthy himself, how is he going to cover the tax bill on $850,000 of gain?

Note that this issue is not shared with other common items of IRD, such as IRAs and other retirement accounts. While such assets are IRD and thus subject to income tax, that bill is only triggered as the beneficiary receives distributions from those accounts. Thus, a beneficiary can account for taxes when the distribution is made by either withholding taxes from the distribution directly, or simply putting aside some of the distribution for the forthcoming tax bill.

This is not the case for a beneficiary inheriting a QOF. Come December 31, 2026, at the latest, that beneficiary is going to have taxable income, even if they have not received so much as a dime in actual spendable money from the inherited QOF asset.

Thus, for beneficiaries with no other way to pay the tax bill, the only option may be to consider selling the QOF on what’s likely a thinly traded secondary market. In such instances a desperate beneficiary forced to sell may only be able to get a fraction of the QOF’s potential value.

OTHER ESTATE CHALLENGES

It may still seem appealing to roll gains into a QOF and just try to dispose of the fund by some other means before death. That won’t work because, as noted earlier, while death is not an inclusion event, almost any other type of pre-death estate planning strategy would be. Gifting an interest in a QOF to a child or other individual would, for example, be an inclusion event and result in the immediate taxation of any still-deferred gain.

This could be particularly problematic for high-net-worth QOF investors if the current $11.4 million unified estate/gift tax exemption — in 2019, adjusted for inflation — were to be reduced either as scheduled at the end of 2026 or potentially sooner via congressional action. This would likely require that Democrats control the House, Senate and White House, as Republicans would likely not support any such proposal.

In either case, if it appears that a decrease in the unified exemption amount is imminent, high-net-worth individuals — bolstered by the

This would be similar to planning that took place toward the end of 2012, when it appeared as if the $5 million exemption was going to go back to $1 million, even though the $5 million exemption was ultimately extended by

In addition, the proposed regulations make clear that the inclusion rules apply to gifts made to both taxable and tax-exempt recipients. As a result, any charitable contribution of a QOF, including a transfer of the investment to a charitable trust, will result in an inclusion event for that owner.

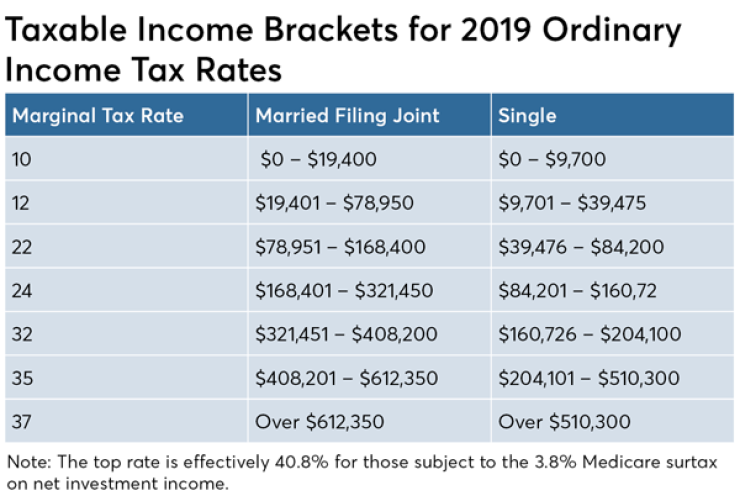

And while a deduction for a charitable contribution may indeed offset most of the impact on a QOF owner’s taxable income — e.g., the inclusion event triggers QOF gains, but then the charitable contribution produces a deduction to largely offset those gains — that charitable contribution would not do anything to reduce the inclusion event’s impact on a taxpayer’s AGI, on which many income-sensitive benefits and costs are based. To name just a few, these would include credits, deductions, Medicare Part B/D premiums and the 3.8% surtax levied under health care legislation enacted in January 2014.

And perhaps even more concerning for some QOF owners is that there appears to be no exception to the inclusion event rules for gifts made to a spouse. Thus, such intra-couple spousal transfers, which are commonly made for estate planning and Medicaid planning purposes to shift assets or equalize estates, cannot be completed without triggering the income tax on any still-deferred gain.

BETTER DEFERRAL STRATEGIES

While QOFs offer some attractive benefits — though a full step-up in basis upon death is clearly not one of them — older investors should first give at least some consideration to other tax-deferral approaches that offer better tax benefits for heirs after their death.

One obvious strategy is simply to do nothing. While an individual may wish to sell an appreciated asset because they believe a better investment option exists elsewhere — or they just no longer believe in the merits of their current investment — in some cases it may pay to hold on to the investment anyway, allowing heirs to receive a step-up in basis at death.

It’s certainly important not to let the tax tail wag the investment dog, but at the same time it’s foolish to look only at the potential gross return of an investment without evaluating the tax consequences of making or changing it. To that end, and while each situation must be evaluated based on its own unique set of facts and circumstances, the following general statements can be used to help guide an investor with appreciated assets toward the best decision.

- The higher an individual’s tax rate, the more holding an asset until death makes sense rather than changing and deferring gain into a QOF opportunity.

- The greater the built-up gain in an investment, the more holding an asset until death makes sense.

- The older the individual and/or the shorter an individual’s life expectancy, the more holding an asset until death makes sense.

- The smaller the gap between the expected return of the new investment and the expected return of the old investment, the more holding an asset until death makes sense.

Another potential strategy for older investors looking to sell highly appreciated business or investment property is the use of a 1031 exchange. Named after the

Notably though, the deferral of gain via a 1031 exchange offers two key benefits as compared to the reinvestment of gain in a QOF. First, there is no end date on the continued deferral of gain provided via a 1031 exchange. Thus, unlike a QOF that forces recognition of any previously unrecognized gain by December 31, 2026, the 1031 exchange can indefinitely defer the gain on a previously sold investment.

Second, and of even greater importance in the context of estate planning, a 1031 exchange does not create IRD for a beneficiary if the owner of the exchanged property dies. Rather, the beneficiary receives a full step-up in basis on the property. From the beneficiary’s perspective, it would be as if the exchange had never occurred, with the same step-up that would have been available on the original asset.

It should be noted, however, that since the passage of sweeping tax legislation in December 2017, the 1031 exchange is only available for sales and purchases of like-kind real property. Thus, an investor with highly appreciated stock or cryptocurrency cannot use a 1031 exchange to defer the gains on the sale of such investments.

For owners of highly appreciated investments who also have a charitable streak, the use of a charitable trust may provide a superior tax minimization and estate planning alternative to a QOF. Such trusts might include

In the case of individuals of an advanced age primarily concerned about providing for beneficiaries, there is also the option of a

Ultimately the key lesson to grasp is that QOFs are not the be-all end-all for individuals holding assets with significant gains. Perhaps nowhere is this truer than for investors nearing the end of their life expectancy.

In fact, the loss of a step-up in basis on reinvested gain for the original QOF owner — combined with a forced tax bill on a likely illiquid asset for a potentially unsuspecting or ill-prepared beneficiary — tends to make QOFs a rather poor investment vehicle to own at death. And that’s to say nothing of the other estate planning challenges created by the inclusion events outlined in proposed regulations from the IRS.

As such, older investors in particular should carefully evaluate other potential gain management strategies, including simply holding tight and doing nothing — and waiting for a step-up in basis — before making a blind leap into QOFs.