Saving for college and retirement can be difficult for many families. Some retirees, however, find themselves in the fortunate position of having enough to cover their golden years and still have something left over to help family members pay for college.

Yet if not done carefully, using a grandparent-owned 529 plan, or gifting assets from a grandparent to grandchild for college, can adversely impact the grandchild’s own ability to qualify for financial aid, implicitly diminishing the value of the gift.

For instance, a grandparent-owned 529 plan is not treated as an asset of the grandchild for financial aid purposes, but distributions from a grandparent-owned 529 plan may show up on the grandchild’s FAFSA financial aid form — even if it’s a qualified tax-free distribution.

Similarly, gifts of appreciated assets from a grandparent to a grandchild may be eligible for 0% capital gains tax rates, but may still adversely impact the student’s income on the FAFSA. And for grandparents trying to diminish their own estates, often the best tactic is simply to make tuition payments directly to the college institution, which can be done above and beyond the annual gift-tax exclusion limits.

Ultimately, grandparents have numerous opportunities for preferential income and/or estate-tax treatment by helping fund college for grandchildren (or other family members). But the financial aid rules — especially when considering the new prior-prior year (PPY) rules for which annual income is reported on the FAFSA — means that coordinating the timing of the various strategies is crucial to avoiding adverse aid outcomes.

GRANDPARENTS' FUNDING OF 529 PLANS

Contributions of up to $14,000 annually (the

Contributions of up to $14,000 annually can be made to a 529 college savings plan without triggering any gift taxes.

CHILD-OWNED VS GRANDPARENT-OWNED 529 PLANS

The question that often arises in the case of grandparents funding a 529 plan is in whose name the 529 plan should be held. Is it better to create the 529 plan with the grandparents as the owner/participant of the 529 plan (with the grandchild as the education beneficiary), or to put the 529 plan in the grandchild’s name outright? Or should the grandparents contribute to a(n) existing or new 529 in the name of the grandchild’s parents instead?

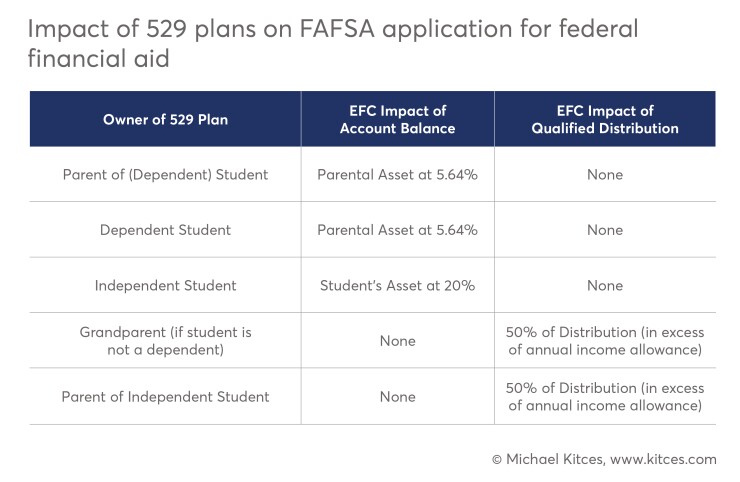

While the income tax treatment of the 529 distributions for the grandchild’s education will be the same in all three circumstances, the key distinction is the treatment for financial aid purposes.

When a 529 is owned by the parents of the student, it is treated as a parental asset for financial aid purposes, which means 5.64% of the value of the 529 plan is counted toward the Expected Family Contribution (EFC). As the FAFSA is filed annually, this amount is recalculated every year on the 529’s account balance as it is spent down. On the other hand, to the extent that the distributions are tax-free qualified distributions from the 529 plan, they are not counted as income for FAFSA purposes.

When a 529 is owned outright by the student, where the student is both the account owner and beneficiary, the asset is still treated as a parental asset for the purposes of financial aid if the student is a dependent. This was a change under the

With a grandparent-owned 529 plan, though, the treatment is different. When a 529 plan is owned by someone other than the custodial parent/guardian of a dependent student (and other than the student themselves), it is not counted as an asset for financial aid purposes — neither at the parents’ EFC rate nor the student’s. However, when distributions are made from a grandparent-owned 529 plan,

While these rules apply for the FAFSA application for federal aid, some colleges use the

Funding 529 college savings plans can be an appealing option for grandparents who get involved early.

GIFTING APPRECIATED INVESTMENTS

Funding 529 college savings plans can be an appealing option for grandparents who get involved early, where there is time for the investments in the 529 plan to actually grow and compound tax-free. However, if the student is already about to go to college, or is already in college, contributing to a 529 plan isn’t very helpful, and other

One appealing option is to gift appreciated assets that are held in the name of the grandparents to the student, in order to sell them in the student’s name, and use the proceeds to fund college tuition or other student expenses. While the $14,000 annual gift-tax exclusion limits must still be navigated, the virtue of gifting the appreciated assets — as opposed to the grandparents simply selling the investments and transferring the proceeds to the student/grandchild — is that gifting investments in-kind allows for the cost basis to carry over to the recipient.

This means that the subsequent sale shifts the capital gains to the grandchild, meaning the student’s lower tax brackets (including, possibly,

The caveat to this strategy is the so-called kiddie tax, which still applies to full-time college students under age 24, unless they have earned income in excess of one-half of their support needs (or if the child is already married and filing his/her tax return jointly with a spouse). As a result,

It’s also important to note that while gifting appreciated securities to the child and selling them in his/her name may be an effective tactic to avoid long-term capital gains taxes at the grandparents’ tax rates, the investment is still an asset in the name of the student, and the gains from the sale are still income in the name of the student. (Even if subject to a 0% tax rate, the gains are still considered income.) Either of these could impact subsequent years of financial aid eligibility. In particular, even if the asset is received as a gift and then liquidated and spent in the same year, such that it never shows up as an asset on the FAFSA, the gains from the sale will still show up as income.

Similarly, even if the grandparents simply gift securities to the parents of the student — which may still generate some capital-gains tax savings if the parents have a lower tax bracket than the grandparents — if the investments are held they will be reported as an asset of the parents, and even if liquidated and spent in the same year as received, the sale of investments in the name of the parents will also still show up as income on the FAFSA, and may adversely impact subsequent financial aid eligibility.

DEMYSTIFYING PRIOR-PRIOR YEAR (PPY) RULES

While both contributions to and distributions from 529 plans can potentially show up as assets or income on the FAFSA for financial aid purposes, and a gift of appreciated securities to the student may end up being reported as an asset or income, it’s crucial to recognize which years will be impacted by this determination.

In the past, income in a current year would count toward financial aid determination in the subsequent year. Thus, the receipt of an asset or the sale/liquidation of an investment in 2010 would count on the FAFSA in 2011 (for the school year that began in fall 2011, that is). Given this dynamic, any asset or income events as late as the first half of junior year could still show up on the FAFSA application for the senior year. Consequently, experts often advised to wait until the student’s senior year to engage in such tactics like liquidating grandparent-owned 529 plans.

However, in the fall of 2015, President Obama signed an executive order that adopted

The significance of these new PPY rules is that it shifts which tax years are relevant when looking at college funding strategies that impact income. In the past, the relevant time window extended from the middle of junior year in high school until the middle of the junior year of college, and students weren’t in the clear until their FAFSA for their senior year had been filed — generally sometime around the end of their junior year.

Under the new rules, however, tax events as late as the second half of sophomore year in high school become relevant, because it will fall in the prior-prior year to when the student matriculates to college. On the other hand, once the student is more than halfway through sophomore year of college, any subsequent income tax events in the junior or senior years will be in the clear, because even the senior year’s FAFSA will be wrapped up based on the prior-prior year tax return that spans the end-of-freshman, beginning-of-sophomore years in college (presuming a student finishes in four years).

GRANDPARENTS PAYING FOR COLLEGE DIRECTLY

Notably, in addition to the usual rules governing the $14,000 annual gift tax exclusion — which applies whether gifts are made in-kind or in cash, to a 529 plan or outright to the child — under

In other words, a grandparent could write a check every year on behalf of a grandchild student for $15,000, $30,000 or even $50,000 for the most expensive tuition in the country, and the payment is entirely free of gift taxes. No use of the annual gift tax exclusion, nor of the lifetime gift exemption; the amount is just outright gift-tax–free.

Under the new rules, however, tax events as late as the second half of sophomore year in high school become relevant.

However, the direct payment of tuition on behalf of a student may potentially be treated as

COORDINATING THE TIMING OF FUNDING

Outright gift-tax-free payments of tuition directly to a college; the ability to fund a 529 plan — whether in the name of the grandparent or the child; or gifting appreciated assets to the grandchild student: Which is the best course, and how should families choose and coordinate between them?

The first key is simply recognizing the age of the student and when he/she is expected to go to college. For those looking to make gifts to support children who are still many years away from college, funding a grandparent-owned 529 will likely be the most appealing, as it allows for tax-free compounding growth for the child. For grandparents who have an outright estate tax problem themselves, it also begins to shift assets out of their estate, and it may be especially appealing to use the five-year-averaging provision.

In situations where grandparent-owned 529 plans are involved, though, it’s important to recognize that those plans should only be liquidated during the student’s last two years in college (ostensibly, junior and senior years for those on the four-year plan), which ensures that the grandparent-owned 529 distributions don’t foul up the student’s EFC calculations when filing the FAFSA. In the early years of college, the grandchild should use their own assets or parental assets.

Notably, if the grandchild plans to go to graduate school, it may be appealing to further delay the use of grandparent-owned 529 plans so the distributions during the undergraduate years don’t impact financial aid for graduate school.

Gifting strategies, where appreciated investments are transferred directly to the student, will be most appealing for those who are able to avoid the kiddie tax. This might be because the student is working at least part-time and is able to provide for one-half of their own support, or because they are not a full-time student. In addition, because the kiddie tax rules only apply to full-time students under the age of 24, gifting appreciated securities may be especially appealing as a tactic to fund graduate school, where the student grandchild will be over the age threshold for the kiddie tax, but may still have income low enough to pay little or no capital gains taxes, because the 0% long-term capital gains tax rate, and the potential offset of any eligible

Given these coordination tactics, using the student’s own 529 plans — either in the student’s or parent’s name — will be most appealing to fund the early years of college. Most of the other tactics are especially inhospitable to funding college in the early years due to their impact on subsequent financial aid. Spending down assets that are counted for financial aid is especially appealing in the early years, as that may improve eligibility for college aid later.

For instance, if the student spends down all 529 plan assets in the first two years, eligibility for financial aid may be improved, which diminishes the amount that grandparents need to supplement with their own gifts or grandparent-owned 529 distributions (after the student is past the FAFSA PPY window).

The bottom line is that grandparents who want to help fund their grandchild’s college education have the opportunity to do so in a manner that helps the family, without impairing the student’s ability to qualify for financial aid, at least for some years. However, it’s crucial to consider the timing of the payments, whether as gifts to the grandchild, payments directly to the educational institution, or distributions from a 529 plan, to minimize any impact to financial aid along the way.

So what do you think? Do you help grandparents coordinate assistance in funding college expenses for grandchildren? Are there other tactics that you recommend? Please share your insights in the comment section.