More than 70 megabanks, tech giants, investment firms and wealth managers failed an influential socially responsible investment manager’s latest ESG screen against firms she says are exacerbating systemic racial injustice.

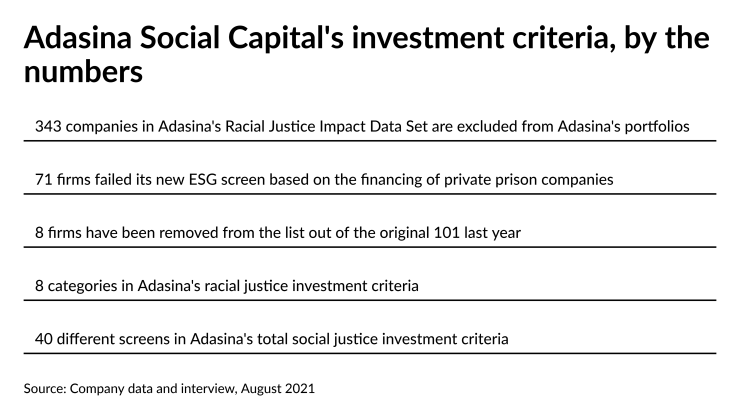

Bank of America, J.P. Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, UBS, BlackRock, Charles Schwab, LPL Financial, Raymond James, Ameriprise and 60 other firms serve as financiers, underwriters or investors in the corporate debt of private prison companies, according to Rachel Robasciotti, CEO of Adasina Social Capital. The new ESG screen added 31 more firms to 312 others not meeting Adasina’s eight-part racial justice investment criteria.

With collaborators in ESG data service YourStake and indexing firm EQM Indexes, Adasina examined roughly 9,000 global companies in the latest update of its “

“Given the small number of companies, only eight, that have been removed from our Racial Justice Impact Data Set over this past year, our data show what many know to be true — that company statements are not the same as company actions,” Robasciotti says in an email.

“Each one of our racial justice screens is zero tolerance, which means the only way for a company to be removed from the Racial Justice Impact Data Set is to put a full stop to the actions they have been flagged for,” she continues. “For example, even if a public company cuts ties with some or most of their private prison investments, they are still considered to be contributing to systemic racism if they have any existing connection with private prisons.”

She adds that, despite many public pronouncements of support for the Black Lives Matter movement from major consumer banks, they’re still providing loans to private prison companies. In 2019, nine major banks stopped working with operators of private prisons and immigrant detention facilities, but only with respect to their future loans,

The other areas covered by Adasina’s criteria include money bail involvement, prison labor, immigrant detention, surveillance and occupied territories, though it has many additional ESG screens in four other categories in its overall “

Less than a year after Adasina started its first investment fund available to clients outside Robasciotti and Philipson’s practice, the Adasina Social Justice All Cap Global ETF has reached $70 million in client assets. In addition to the firms listed above, Adasina excludes any holdings in Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, Invesco, Envestnet, Alphabet, PNC Bank, BNY Mellon and Bank of Montreal from its portfolios based on the racial justice criteria.

Representatives for Morgan Stanley, Bank of America and Microsoft declined to comment, while 16 other firms didn’t respond to email inquiries about Adasina’s findings. PNC Bank Director of Corporate Public Relations Marcey Zwiebel questioned the accuracy of the data.

“While we’re not familiar with the criteria Adasina is applying to their analysis, PNC Capital Advisors does not invest in securities that fund private prison companies,” Zwiebel said in an email.

It’s often difficult “to fully determine the scope of a company’s ESG risks and impacts, including around racial justice,” Rachel Curley, a democracy advocate with the nonprofit consumer advocacy organization Public Citizen’s Congress Watch division, said in an email.

The organization is calling for the SEC to create mandatory ESG reporting standards enabling professionals, clients and the public to compare companies among each other and track it over time. Many firms are disclosing ESG data, but the information can be incomplete, Curley says.

“It’s important for investors to have a full view of a company’s racial justice impacts,” she says. “Increasingly, companies face reputational risk from saying one thing publicly and doing another out of sight. If a company makes public commitments to racial justice, it’s important for investors and customers to understand how the company thinks about and manages racial justice impacts throughout its operations, including its relationship to the private prison industry.”

Adasina’s Racial Justice Impact Data Set began last year with 101 companies, according to Robasciotti. The small number of firms the fund manager has removed since then had been cited for discrimination in workplaces and public accommodations in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank. Adasina doesn’t seek to divest from Israel through the boycott, divest and sanction framework. The manager hasn’t removed any companies it previously put on the list based on other screens, though it added a “status” for each one in case they do modify their practices.

“If people are asking what they can do to fight for racial justice, one of the most immediate and accessible steps they can take is to stop giving their investment dollars to companies that exacerbate racial inequities,” Robasciotti said in a statement. “We’ve continued to make this data set available to the public to mobilize investors and others to use their money, and their voices, to influence companies and governments who are on the wrong side of history.”