On December 20, 2019, the Setting Up Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE Act) was passed into law. While the law made a substantial number of revisions to the rules for retirement accounts, no single change received more attention than the SECURE Act’s rewriting of the post-death distribution rules that apply to most non-spouse beneficiaries of retirement accounts.

More specifically, prior to the SECURE Act, all designated beneficiaries (living individuals, along with

SECURE Act’s new 10-year rule for non-eligible designated beneficiaries

The SECURE Act

The

Compared to the ‘old’ ‘Stretch’ rules, the 10-Year Rule has the potential to dramatically accelerate distributions from the inherited retirement account to the beneficiary. For instance, under the ‘old’ rules, a 35-year-old healthy child would have been able to stretch distributions over nearly 50 years (the

Clearly, the loss of tax deferral for several decades or longer can have a dramatic impact on the net-after-tax value of the inherited account. Accordingly, since the SECURE Act was passed, practitioners have been exploring ways to mitigate the imposition of the 10-Year Rule.

Charitable remainder trusts offer similar benefits to the ‘stretch’

One planning vehicle that has received a substantial amount of attention since the passage of the SECURE Act is the Charitable Remainder Trust (in particular, the Charitable Remainder UniTrust, or CRUT). More specifically, as a way to mitigate the impact of the ‘death’ of the ‘Stretch,’ some practitioners have suggested naming would-be Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries as the income beneficiaries of a CRUT, and then naming that CRUT as the beneficiary of the individual’s retirement account (instead of naming the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries directly on the beneficiary form).

At the most basic level, a CRUT is a trust that receives assets, makes ongoing distributions of those assets (and their earnings) for some period of time (as described further below) to a named beneficiary, and then terminates and sends whatever is left in the trust (the remainder) to a qualifying charity.

Notably, CRUTs have the potential to offer certain individuals similar benefits as would have been provided by the ‘Stretch.’ Tax deferral, for instance, is a benefit enjoyed by both an inherited retirement account and a CRUT. As a charitable entity, a CRUT does not pay income tax on any income it receives. In the case of a CRUT named as the beneficiary of an IRA, such income would include distributions from the IRA to the CRUT, as well as any interest, dividends, and capital gains earned within the trust.

Additionally, CRUTs can be established to distribute assets annually in a ‘Stretch’-like manner over an individual’s (or group of individuals’) life expectancy (or for a fixed period of up to 20 years). And similar to the ‘Stretch’, income beneficiaries of a CRUT pay taxes on the distributions they receive (from the trust) on their personal returns.

Basic Charitable Remainder UniTrust (CRUT) rules

Clearly, there are a number of benefits to the use of a CRUT. But using a CRUT to secure those benefits is far from a ‘free lunch.’ Rather, in order to qualify as a CRUT (and take advantage of the corresponding tax benefits), a trust must meet a number of requirements.

IRC Section

Meanwhile,

Thus, younger beneficiaries will generally receive larger distributions from a CRUT established for their benefit, than they would have under the ‘Stretch.’ For example, as noted above, the Single Life Expectancy factor for a 35-year-old is 48.5. Thus, using the ‘Stretch’ rules, such a beneficiary would only be required to take a distribution of 100 ÷ 48.5 = 2.06% from their inherited retirement account, and wouldn’t be required to take a distribution of 5% or more from their inherited IRA for another 29 years (when their RMD factor would be 48.5 – 29 = 19.5, resulting in a 100 ÷ 19.5 = 5.13% required minimum distribution)! By contrast, the same 35-year-old beneficiary would be required to receive a distribution of no less than 5% of the assets of a CRUT for which they were named a beneficiary.

Finally, it’s worth noting that whereas all distributions from inherited IRAs are considered ordinary income, a CRUT retains the character of any income it receives or generates, and then distributes that income to trust beneficiaries on a worst-in, first-out basis, distributing first any ordinary income, then long-term capital gains or dividends, and only then any tax-free income (such as from municipal bonds), followed lastly by any distributions from the non-taxable principal. In other words, if a CRUT has capital gain income, it can distribute those amounts to the CRUT beneficiary, but it can only do so after first distributing all ordinary income (because ordinary income is ‘worse’ income that is taxed at a higher rate!).

The end result is that, while CRUTs can replicate a similar tax-deferred ‘stretch,’ younger beneficiaries may face larger distributions, and those distributions will always be ordinary income first, to the extent there is any ordinary income that the CRUT has ever received to distribute.

Using a CRUT as a wealth-transfer vehicle is rarely the ‘best’ option

On the surface, the CRUT appears to be a reasonably close approximation to the ‘Stretch.’ But unlike the pre-SECURE Act ‘Stretch’ rules, not every person can be the beneficiary of a CRUT. And upon closer inspection, even when the CRUT can be used, for those who are primarily interested in transferring as much wealth as possible to heirs, the CRUT will rarely be the optimal solution.

Some individuals are too young to be CRUT beneficiaries

As noted above, in order to qualify as a CRUT, a trust must both distribute at least 5% of its assets annually, and have an actuarial value of the remainder interest of the trust equal to at least 10% of the initial contribution to the trust. That required combination makes it impossible to name “young” individuals as the beneficiary of a CRUT (or to even be included amongst a group of named beneficiaries).

Simply put, young individuals’ long (actuarial) life expectancies make it mathematically impossible to construct a CRUT that satisfies both the payout and remainder (to charity) requirements. If you set the payout rate of the trust even at the lowest permissible payout rate of 5%, the beneficiary will receive those distributions for somany years that the projected remainder amount ends up being less than 10% of the original balance. Similarly, if you set the actuarial remainder amount at the lowest permissible level of 10% and solve for the payout rate, the required payout rate over the life expectancy of a very-young beneficiary that still leaves at least 10% as the remainder would necessitate a payout rate less than 5%. Regardless of which way you go about it, the result is the same. You can’t make the would-be CRUT work for a young beneficiary.

Of course, that raises the obvious question: “How young is ‘too young’ to be a CRUT beneficiary?”

The answer, as is often the case, is “It depends.” More specifically, the youngest possible age for a CRUT beneficiary generally hovers somewhere in the mid-20s, but the exact age varies from time to time. Because the payout of a CRUT is based both on the age and life expectancy of the beneficiary – which determines the number of years it would be anticipated to pay out – and an assumed growthrate. The higher the growth rate, the longer the CRUT can sustain distributions (even at its 5%-minimum-payout rate), and the younger the CRUT beneficiary can be without running afoul of the CRUT requirements.

Notably, the interest rate used to calculate the actuarial value of the remainder interest of a CRUT is known as

As noted earlier, as the Section 7520 rate decreases, the youngest possible age for a CRUT beneficiary increases. Thus, for example, using a Section 7520 rate of 1.2% – the highest possible interest rate that can be used for a CRUT funded in June 2021 – it is mathematically impossible to construct a valid CRUT that pays out over the life of a beneficiary who is under the age of 27. By contrast, using a Section 7520 rate of 6.2% (last applicable in August 2007), the youngest possible age for a lifetime payout CRUT beneficiary drops to 25 years old.

Even using an astronomical (at least by today’s standards) Section 7520 rate of 20%, the youngest possible CRUT beneficiary would be 18 years old. Accordingly, it is highlyunlikely that a CRUT could be used to re-create the ‘Stretch’ for a minor beneficiary. And because it is impossible to know, in advance, the Section 7520 rate that will exist at the time of an individual’s death, CRUTs generally should not be considered for use until the intended beneficiary is at least 27 or 28 years old.

CRUTs don’t make sense for older beneficiaries with shorter life expectancies

When it comes to using CRUTs as ‘Stretch’ replacement vehicles, “young” individuals are ‘out’ by rule. At the opposite end of the pendulum, older individuals can be named as the beneficiary of a CRUT with a lifetime payout, but doing so does not make financial sense for IRA owners primarily concerned with wealth transfer to heirs.

Notably, the primary tax benefit provided by the use of a CRUT as an IRA beneficiary is that gains are tax-deferred for as long as they remain in the CRUT. The 10-Year Rule, though, essentially the ‘default’ option to which the CRUT is being compared, already provides tax-deferral at least for a decade. Accordingly, individuals with a life expectancy of less than a decade would not be expected to gain any additional tax deferral through the use of a CRUT than they would through the use of the 10-Year Rule to which they would be entitled simply by being named directly on the beneficiary form.

Additionally, and of even greater importance, it’s important to remember that the tradeoff for a CRUT receiving its tax deferral is that once the income beneficiary of the CRUT dies, whatever is left in the trust (which must be actuarially expected to be at least 10% of the present value of the trust upon contribution) goes to charity. Thus, there is an ever-present risk that the CRUT beneficiary will have a premature death, resulting in a substantial reduction in generational wealth transfer. And an older beneficiary has an even greater risk of dying relatively soon after the CRUT is established (before it makes enough distributions to be more valuable than simply relying on the 10-year rule).

Example 1. Suppose a $1 million IRA was left to a CRUT with a 60-year-old beneficiary. The optimal payout percentage for such a trust, based on the life expectancy of a 60-year-old beneficiary and the required remainder for a charity, is 14.903% per year (just take my word on this calculation). What if, however, such a beneficiary unexpectedly died after receiving only one distribution from the CRUT?

In this case, the beneficiary would have received just 14.903% × $1 million = $149,030. The remaining amount in the CRUT (the $1 million IRA less the $149,030 distribution, plus/minus any gains/losses) would go to charity.

In other words, while the charity must be due to receive at least 10% of the value of the trust as the remainder at the beneficiary’s life expectancy, if the beneficiary dies sooner, the charity may receive far more. In this case, the charity actually receives more than 85% of the inherited IRA! Thus, while the charity would receive a windfall, generational wealth transfer would be largely destroyed by the early death.

Of course, the risk that a beneficiary dies shortly after becoming the beneficiary of a CRUT is always present. But older beneficiaries have higher mortality rates, and therefore a greater risk of a ‘catastrophic’ loss of the CRUT remainder by dying after receiving relatively few distributions.

Life insurance can be used to mitigate this risk, but it too comes at a cost. And the more likely the CRUT beneficiary is to have a limited life expectancy (either due to advanced age or to health issues), the greater the expense of purchasing a life insurance policy, if such a policy will even be issued! Which further limits how much upside can ever be created by trying to take advantage of the CRUT’s quasi-stretch benefit in the first place.

It can take a (really) long time to reach the break-even point with a CRUT

CRUTs as beneficiaries of retirement accounts don’t eliminate income taxes. They just delay (defer) them. Thus, for IRA owners primarily concerned with transferring wealth to future heirs, the projected additional wealth made possible by the CRUT’s extended tax deferral (compared to the 10-Year Rule) has to outweigh the projected loss of (at least) 10% of the assets left by the CRUT to the charity.

Is that possible? Can extended tax deferral make up for the remainder amount that must be left to charity (thereby enabling an IRA owner to transfer more wealth to future generations using a CRUT than they could have by naming the CRUT beneficiary directly on the IRA beneficiary form?

Indeed, in certain situations, it is quite possible.

But it generally takes a really long time.

The breakeven point – the amount of time it would take for wealth created via distributions from a CRUT (as any balance remaining in the CRUT will go to charity) to catch up to wealth created via leaving the same amount of retirement dollars to a beneficiary directly under the 10-year rule – varies based on a variety of factors, including the:

- CRUT beneficiary’s ordinary income tax rate

- CRUT beneficiary’s long-term capital gains rate

- Percentage of the growth of the CRUT that is comprised of ordinary income versus capital gain income

- Turnover of CRUT investments (which triggers capital gains to be distributed)

- CRUT payout percentage

Notably, while the exact break-even point varies (per the above factors), it generally takes a CRUT three or more decades for its tax deferral to make up for the amount that is ‘lost’ to charity upon death of the beneficiary.

Example 2. Mary has a $2 million IRA which she plans to leave to her healthy 34-year-old twin sons, Bill and Ted. Mary’s primary goal is to transfer as much wealth to her two boys as possible upon her death.

Bill and Ted are both highly compensated consultants who work for the marketing agency, “Excellent Ad Ventures.” Currently, their income from the ad business puts them in the 33% ordinary income tax bracket and 15% long-term capital gains bracket.

Since both Bill and Ted are healthy 34-year-old adults, they are Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, subject to the SECURE Act’s 10-Year Rule. Ted is concerned about the limited deferral provided by the 10-Year. Accordingly, he creates a lifetime payout CRUT, and asks his mother to leave his share of the IRA to the CRUT instead of him directly. Bill, on the other hand, wants to remain the direct beneficiary of his mother’s retirement account, and plans to spread distributions from the account evenly over the 10 years after he inherits.

Sadly, moments after updating her beneficiary form to list Bill as a direct beneficiary of 50% and Ted’s lifetime payout CRUT as a beneficiary of 50%, the twins’ mother passes away.

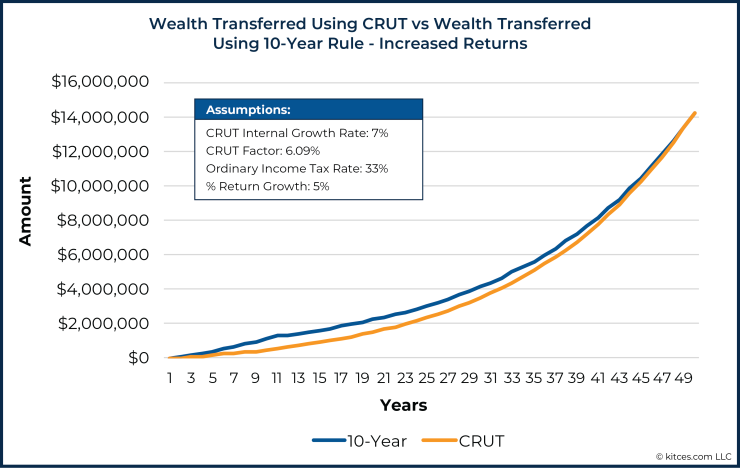

As the graph below indicates, if the twins invest their respective accounts identically, (based on the assumptions described below) it would take Ted exactly 50 years(!) to accumulate as much wealth using the CRUT as Bill accumulated by being named a beneficiary directly (even given the impact of the 10-Year Rule). Notably, by that time, both twins would be 85 years old, which is actually longer than the actuarial life expectancy of the 35-year-old male!

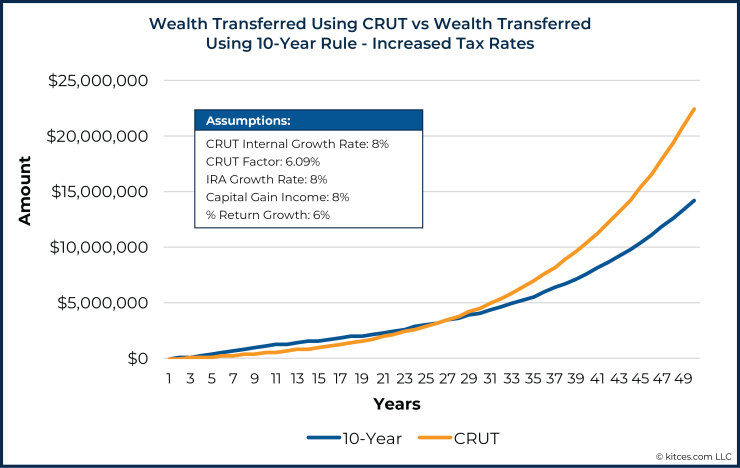

Of course, as an individual’s tax rate increases, so does the value of tax deferral. So, what if Bill and Ted’s business took off, and they found themselves in the highest tax brackets? How would that change things?

As the graph below indicates, increasing Bill and Ted’s tax rates shifts forward the breakeven point… but only by a few years. More specifically, it would (still) take Ted 46 years(!) to catch up to Bill’s wealth using the CRUT.

The value of tax deferral also increases as returns increase (assuming any interest, dividends and/or net positive capital gains). So, what if Bill and Ted were able to squeak out a bit higher tax-preferenced (capital gain) return?

Well, once again, the breakeven point shifts forward. And as the chart below shows, the combination of the higher tax rate and increased rate of return results in a much more reasonable (but still very long!) break even point of 32 years.

In other words, if Ted lives at least 32 years – until his late 60s – then any growth beyond that point (under these assumptions) would leave him better off than Bill. If Ted passes away any earlier, though, his outcome with the CRUT is worse.

Other downsides of using a CRUT as a retirement account beneficiary

As the third scenario above shows, there are certainly some situations where a CRUT could be expected to transfer more wealth to an heir, over time, than leaving them a retirement account outright.

That said, even in such situations, there are additional complications of using a CRUT as an IRA beneficiary that should be considered. Such issues include the following:

- The loss of optionality - If an individual is named the income beneficiary of the CRUT, they are entitled to ongoing distributions from the trust, but they generally have no ability to access any additional amounts in the trust. In other words, if they want or need more, they have no access to the CRUT assets to use more. By contrast, if a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary inherits a retirement account, they have access to the full inherited amount right away. Taxes, of course, would be owed on any additional distributions above and beyond the required minimum, but that is at least an option for the beneficiary to consider (which is lost with a CRUT).

- CRUTs have organizational and operational expenses – A CRUT is a legal document, and as such, it should be drafted by a qualified legal professional (who won’t be free!). In addition to the upfront cost of establishing a CRUT, though, there are generally ongoing expenses. For instance, the CRUT must file a tax return each year, which, given the complexity of such returns, will likely require the assistance of a qualified CPA or other tax professional. Another cost that must be overcome with the CRUT’s benefits of tax deferral (which pushes the breakeven period out even further).

It takes a (near-) perfect storm for a CRUT to be the best wealth-transfer vehicle

Ultimately, it’s not a stretch (Ha! Get it?) to say that it takes a near-perfect storm for an individual to find themselves in a situation where naming a CRUT as the beneficiary of their retirement account will be better off for their beneficiaries from a wealth-transfer perspective than simply accepting the reality of the 10-Year Rule as a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

If the intended beneficiaries are too young, it won’t even be possible to use a CRUT. If the beneficiaries are too old (or sick), there won’t be enough time to allow the tax deferral of the CRUT to make up for the remainder value that will ultimately be ‘lost’ to charity.

Similarly, if the CRUT beneficiary is in a more modest tax bracket, the tax deferral that the CRUT offers won’t be worth much. And if expected returns are more modest, the value of the CRUT’s tax deferral is similarly muted.

So, ultimately, for the owner of a retirement account to name a CRUT as their beneficiary in an effort to maximize wealth transfer to an heir, they have to have a ‘Goldilocks’ beneficiary (not too young, nor too old), in a fairly high tax bracket for the indefinite future, who expects to have fairly strong portfolio returns over time.

And even if all that ‘adds up,’ the beneficiary will have to actually live long enough to see the net benefit.

Charitable intent can make the CRUT option more attractive

It’s worth noting that it doesn’t take the near-perfect storm described above to make naming a CRUT as an IRA beneficiary a viable planning strategy. Rather, the near-perfect storm is just required when the CRUT is being used to maximize wealth transfer. But maximizing wealth transfer is not always a retirement account owner’s goal, or at the very least, their only goal. Sometimes an individual may wish to provide a benefit for heirs, as well as for charity. In such situations, a CRUT could see increased value as a planning tool.

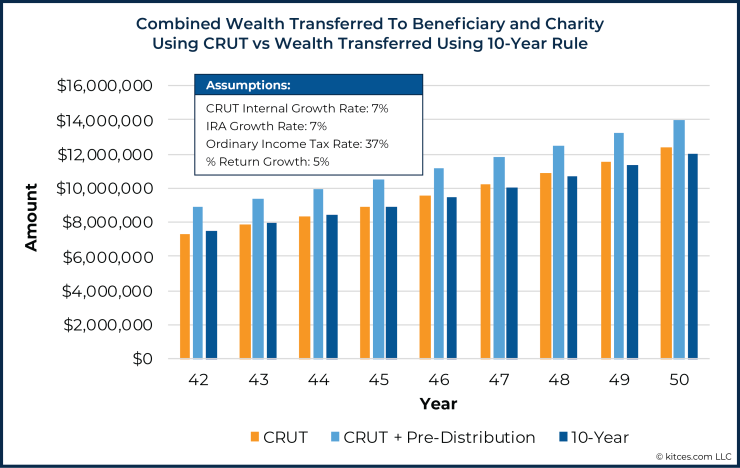

Example 3. Recall Bill and Ted from Example 2. Bill inherited $1 million of IRA money directly, while Ted was named the income beneficiary of a CRUT that was the beneficiary of another $1 million of IRA funds. In the first scenario, it took Ted 50 years to catch up to Bill's wealth using the CRUT.

Consider, for a moment, though, what would have happened if Bill and Ted each died 40 years after inheriting the IRA. At that time, Ted would have trailed his brother by about $400,000 in net wealth created via the inheritance.

But looking purely at the brothers’ comparative wealth completely discounts amounts left to charity. Notably, in Bill’s case, there is nothing left for charity (of course, Bill could always leave some of his own assets to charity). On the other hand, as the graph below illustrates, the CRUT established for Ted still has nearly $1.5 million left that would all go to charity.

For some retirement account owners, that trade-off (reducing an heir's wealth by a little, to increase the amount that goes to charity by a lot) might be well worth it. Or viewed another way, while Ted and his heirs didn’t end up benefiting from the CRUT, the charitycertainly did (at Uncle Sam’s expense!).

Since the SECURE Act effectively ‘killed’ the ‘Stretch’ for most non-spouse beneficiaries, retirement account owners and planners have been exploring ways to mitigate the impact of the new 10-Year Rule. One of the more popular concepts being discussed is the potential use of a CRUT as an IRA beneficiary to try and create a pseudo-stretch IRA.

Indeed, a CRUT can allow for many similar benefits to the stretch. Specifically, assets held within the trust remain tax-deferred, as is the case with an inherited retirement account. Similarly, a CRUT can be established to provide an individual with distributions over their life expectancy, similar to the ‘Stretch.’

But CRUTs are no ‘free ride.’ Such trusts require beneficiaries receive a fixed rate of at least 5% of the trust assets each year (in no more than 50%), and at least 10% of the actuarially determined present value of the trust must go to charity.

The ‘loss’ of 10% of trust assets to charity can be ‘overcome’ by a CRUT’s tax deferral, but only in the right circumstances. In general, CRUT returns must be strong, the CRUT beneficiary must be in a reasonably high tax bracket, and the CRUT beneficiary must live three, four, or even five decades or more after the CRUT has been funded.

If just the right circumstances present themselves, or if a retirement account owner is sufficiently charitably inclined, naming a CRUT as the beneficiary of a retirement account is a planning strategy worth exploring. But for retirement account owners solely looking to maximize the transfer of wealth to heirs, the bottom line is that a CRUT is generally not a great (or is at least, a risky) option.

Jeffrey Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, MSA, a Financial Planning contributing writer, is the lead financial planning nerd at Kitces.com, and director of advanced planning for Buckingham Wealth Partners.