The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is attempting to squash a three-year lawsuit accusing the private research university of breaching its fiduciary duty in employee 401(k) plans — an allegation that stems from its relationship with Fidelity Investments.

In a class action lawsuit originally filed in 2016, five former and current MIT employees allege that the school used Fidelity for recordkeeping in exchange for sizable donations — despite recommendations from a consultant to consider alternatives.

Fidelity CEO Abigail Johnson sits on the board at MIT, and Fidelity has given the institution multimillion-dollar donations on several occasions, according to Jerry Schlichter, lead attorney for the former and current MIT employees.

MIT and the individuals named in the lawsuit deny the allegations, according to a response filed with the lawsuit.

“MIT is proud of the careful work of the voluntary faculty and senior administrative staff members of the internal committee overseeing MIT’s supplemental 401(k) plan,” MIT spokeswoman Kimberly Allen wrote in a statement. “The lawsuit against MIT and these committee members, individually, is one of many cases filed against universities by the same law firm. MIT has and will continue to vigorously defend against the claims asserted in this lawsuit.”

The law firm representing the MIT plan participants, Schlichter, Bogard & Denton, is considered a pioneer in retirement plan litigation. The firm settled a few months ago with power grids and robotics company ABB for $55 million following a lengthy lawsuit that also involved Fidelity, according to the

Fidelity, which is not a defendant in the case, denies the claims in the MIT lawsuit.

“The judge previously dismissed a claim to this effect from the case, and nothing new has come to light that makes this story any more plausible now than it was then. Consequently, we believe that these assertions are completely fictional and wholly irresponsible,” says Fidelity spokesman Vincent Loporchio.

Loporchio noted that Schlichter, Bogard & Denton had improperly quoted an MIT employee as a Fidelity executive in a

The employees originally sued the institution over breach of fiduciary duty of loyalty and prudence, prohibited transactions between plan and party in interest and failure to monitor fiduciaries.

In an August 2017 hearing over a motion to dismiss the claims, Judge Marianne Bowler denied the claim of breach of duty of loyalty, but allowed the claim of breach of duty of prudence, according to court documents.

-

The new open architecture platform will minimize the “swivel chair experience” for advisors.

June 11 -

The transparency of a fee charged to other fund firms for use of the platform is allegedly questioned.

February 27 -

The firm's partnership with software issuer BondLink aims to expand access to aggregated issuer data.

March 29

After about two years of discovery, the plaintiff attempted to amend the complaint to once again include breach of duty of loyalty, according to Schlichter.

Last week, Schlichter, Bogard & Denton filed 115 exhibits in a federal court in Massachusetts. The documents include emails and meeting notes from Fidelity and MIT employees that the law firm says point to a quid pro quo relationship between the brokerage and institution.

Starting in 2009, Mercer, a global consulting company, informed MIT it was overpaying for recordkeeping compared to standard industry cost and recommended looking into alternatives, according to the motion. The motion also referenced an instance in July 2016 when Mercer made similar recommendations.

“To this date, [MIT has] never even investigated alternative vendors or considered removing Fidelity as the plan’s recordkeeper,” the motion reads.

MIT employees allegedly cited Johnson’s position on the board as a barrier for considering alternative recordkeepers, according to the motion.

In a June 2009 meeting regarding the 401(k) plan, Theresa Stone, MIT’s then-chair of the plan’s oversight committee, noted that the school must be sensitive to Johnson being “a member of both the MIT Corporation and MITIMCo’s Board of Trustees."

"She is Chair of the Board that oversees Fidelity’s 161 fixed income and asset allocation funds which handle about $650 billion of the more than $1.2 trillion managed by Fidelity,” according to meeting notes obtained during discovery.

In 2014, the chair of the committee following Stone, Israel Ruiz, allegedly directed an employee to hold off on a decision about retaining Fidelity as an index fund provider until Johnson’s term as chair of the MIT Sloan School of Management Visiting Committee had ended, according to the motion filed with the lawsuit.

“[Ruiz] attempted to avoid and delay eliminating Fidelity’s proprietary investments,” the motion reads.

Later that year, the university’s former director of benefits, Maureen Ratigan, allegedly asked Ruiz whether she should notify Johnson or other senior Fidelity employees that MIT had discussed potentially eliminating Fidelity funds. Ratigan allegedly wrote that MIT should avoid “‘any appearance of Fidelity’s exerting influence over our fund selection process,’” according to the motion.

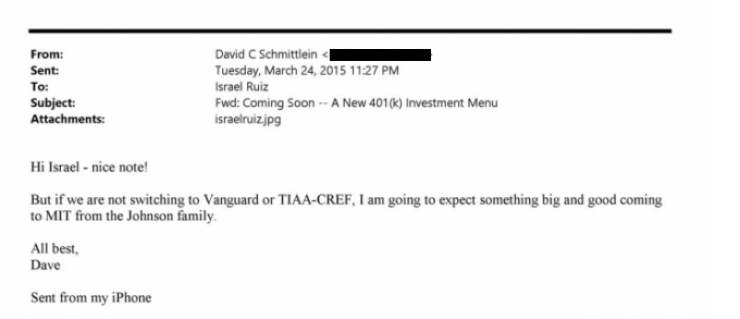

In 2015, David Schmittlein, the dean of MIT's business school, allegedly wrote Ruiz in an email: “If we are not switching to Vanguard or TIAA-CREF, I am going to expect something big and good coming to MIT from the Johnson family,” according to the email attached with the filings.

Soon after, MIT received a $5 million donation from Fidelity — the largest gift Fidelity had given the university in 15 years, according to Schlichter. Fidelity has given a total of $23 million in donations to MIT since 2001, Schlichter says.

MIT received nearly $985 million in contributions and grants overall for the fiscal year ending in June 2016, according to the institution's

The lawsuit also alleges a Fidelity employee took an MIT employee to a basketball game and discussed the retirement plan on at least one occasion, according to an email from discovery.

“We learned that the fiduciary committee chairman was taken out to the Boston Celtics NBA finals game [by Fidelity employees], where the plan was discussed,” Schlichter says.

MIT’s gift policy prohibited employees from accepting personal gifts or gratuities from vendors, subcontractors and contractors, according to the policy, which is included in court documents.

Fidelity spokesman Loporchio declined to comment on whether Fidelity had ever provided sports tickets or other forms of entertainment to MIT employees.

“Whether Abigail Johnson knew that [MIT] made decisions to curry her favor is also irrelevant,” according to the lawsuit. “The facts and circumstances demonstrate that [MIT] made choices in Fidelity’s interests because they believed it strengthened their relationship with Abigail Johnson and Fidelity.”

The motion, which was made in order to reassert the claim for breach of loyalty, was denied Thursday by Judge Nathaniel Gorton, according to the order, which states there is inadequate time for MIT and named defendants to rebut an additional legal theory.

MIT filed a motion for summary judgment on the case in mid-July, stating the plan fiduciaries “followed careful, deliberative processes in making decisions” and that investment options and fees were reasonable and consistent with market rates.

The trial is scheduled for Sept. 16.