Life expectancy is on the rise, but you wouldn't know it talking to American adults today. Research shows that middle-aged and older Americans consistently underestimate how long they're likely to live — a misconception with major implications for retirement planning.

But financial advisors may be able to help close that gap. A

The study, which surveyed 1,950 individuals aged 45 to 70 in the first quarter of 2025, divided survey respondents into three groups: one control group and two intervention groups.

The control group read material that had nothing to do with life expectancy, survival rates or mortality trends. The first treatment group was shown information derived from Social Security death records about their likelihood of living to ages 90 and 100. The second treatment group was presented not only with survival probabilities, but also with information about

Researchers have observed that people — including 59% of participants in the study — often form their life expectancy beliefs on how long their parents or relatives lived, though the effects of that on one's own life expectancy had not been tested before.

Afterward, all the groups were asked to estimate how long they expected to live and their chances of reaching ages from 75 to 100.

Overall results from the experiment were mixed, with just a quarter of respondents altering their

A unique group with exceptional trust in advisors

Whether participants were affected by the intervention came down to one major factor: What source of information informs their life expectancy estimates.

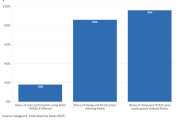

When asked what informs their view of life expectancy, respondents pointed to one of three major sources: a parent or relative's age of death (59%), a medical professional or

Only the second group — those whose life expectancy view is informed by professional advice — were significantly influenced by the intervention.

Among that group, those who received information about life expectancy from Social Security death records were eight percentage points more likely than the control group to say they will live at least until age 85.

Those who received additional information about how their life expectancy compared to their parents also increased their estimates, but not by as much.

"Providing simple material works just as well, if not better, as interventions with more detail," researchers wrote. "While neither intervention was particularly long, our results showed that merely providing some data — on the likelihood of living to specific ages — was enough to increase respondents' perceptions of surviving to older ages, and offering more data on mortality reductions over time did not improve outcomes."

Outside the lab, advisors tackle life expectancy every day

For advisors, a client's estimate of how long they'll live isn't just a data point — it's the foundation of their entire retirement plan. So what does this research mean for financial advisors working with older clients today?

Above all, an advisor should be mindful of what their client is basing their expectations on. Is it rooted in the mortality of older family members? Professional advice? Media coverage? Or something else entirely?

The answer to that question has major implications for how well they can expect their client to respond to information about life expectancy. For now, research shows that individuals see little change after being presented with mortality information, unless they already base their view on the opinions of professionals.

Within that group, it's still worth explaining what life expectancy really means in terms of individual outcomes.

"I always bring clients to

Given that variability, many advisors err on the side of caution when it comes to estimating a client's life expectancy — if they estimate it at all.

Lora Hoff, a wealth manager at Wealth Partners Alliance in Dallas, said she runs every client's plan to age 100.

"I typically just cheerfully say that 'I prefer to plan to age 100, because I don't want to be the one to kill somebody off early.' Usually, the client just laughs about it, but if they press me on it, I say that 'If I plan for you to be fine to 100 and you end up not living that long, then you will just have more for your heirs, but if we plan too short, then nobody wants that result.'"

Given most people's predisposition to anecdotal evidence, other advisors find it helpful to offer examples of cases where people live far longer than the estimates would project.

"One example I share is one of my relatives in his late 90s with numerous comorbidities who remains alive and well," Nicole Sullivan, director of financial planning at Prism Planning Partners in Libertyville, Illinois. "He is a testament to the power of modern medicine. I remind clients that outlier circumstances like this can occur, and therefore, we take a conservative approach in our financial planning assumptions. Life can often surprise us!"