With tens of millions of American retirees depending on their Social Security benefits, two competing proposals aimed at ensuring the program’s solvency have emerged in Congress. But Capitol Hill watchers warn that finding a consensus on how to fix the underfunded entitlement program won’t be any easier for this Congress than in prior sessions.

One bill in the Senate has attracted bipartisan co-sponsors, but the legislation would leave any direct changes to the program up to a “rescue committee” charged with drafting legislation. A more comprehensive bill intended to make the program solvent until the year 2100 has support from Congressional Democrats and resembles the plan

Americans “haven't seen much progress” when it comes to Social Security legislation for nearly 40 years, according to Shai Akabas, director of economic policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center. The think tank views the idea of another commission about Social Security as, at least, a way of advancing the debate, he says. But critics warn of potential cuts to benefits and continued legislative gridlock; most favor increasing payroll taxes on high earners as a better way to shore up the program.

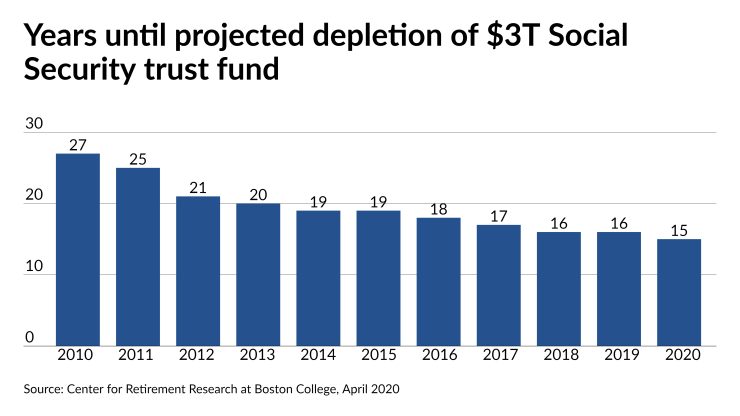

“The program faces a significant financial imbalance between the revenues that it's bringing in and the benefits that it's paying out, and that gap is projected to grow substantially over time,” Akabas says. “The sooner we address the problem, the more gradual the solutions will be and the more easy it will be to close that hole.”

The Time to Rescue United States’ Trusts

“Getting our country through the COVID-19 pandemic has required us to borrow trillions of dollars, which has in turn threatened essential programs like Medicare and Social Security,” Romney said in a statement. “Congress must respond in a way which will address this long-term problem, which is coming down the pike much sooner than was expected.”

Rep. John Larson, a Democrat from Connecticut who is chairman of the Social Security Subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee, has introduced the

“In the late spring Rep. Larson will be re-introducing legislation that will strengthen and enhance Social Security,” Mary Yatrousis, the communications director in Rep. Larson’s office, said in an email. “He is working with the Biden administration and Congressional Democrats on the legislation.”

With 209 co-sponsors in the last

Any legislation that comes out of the committee assembled under Sen. Romney’s bill faces the same challenge, according to Mary Johnson, a policy analyst with the nonpartisan Senior Citizens League. The organization hasn’t taken a position, but Johnson expressed skepticism.

“I have witnessed many commissions, committees, whatever you want to call them that have had stellar appointees...None of them were ever effective in getting legislation passed,” Johnson says. “It still requires 60 votes. It would encounter that same problem that we have with every bill and even more so, because it’s Social Security.”

As one of many advocates decrying

The economic impact of the coronavirus could worsen the overall solvency of the program and make the policy questions even more urgent. The trustees of Social Security

“It's really concerning that Social Security, which is supposed to be the foundation of retirement security for millions and millions of Americans across the country, has now become their greatest uncertainty for financial planning,” he says. “There's no indication from policymakers as to how they're going to address that challenge, and that's really not fair to millions of beneficiaries and millions of future beneficiaries.”