If asked to list the desirable properties for an investment portfolio, most investors would place diversification and cost at the top of the list--likely in that order. While the word “cost” can apply to many things, such as portfolio management fees, transaction costs, or even liquidity, it remains relatively unambiguous. Diversification, on the other hand, is less well understood. What investors really want is efficiency, the concept that encompasses both cost and diversification.

There’s really no universally accepted definition of portfolio diversification. Broadly it refers to mixing different types of securities together that respond differently to the same stimulus. Because of this, they rise and fall in value at different times and this, in turn, prevents the portfolio from going south in the instance of one or two bad events. On the other hand, it will prevent the portfolio from going through the roof when terrific events occur. The operative concept is that investors place more weight on bad events, like a loss of $1,000, than on good events like a gain of the same amount. This is the concept of “risk aversion” and it is what makes risk in an investment setting different from risk elsewhere.

A key concept is that of “systematic risk.” This is the risk that cannot be diversified away—the risk of the market itself. In other words, if you have one stock, nearly all of the risk is coming from factors associated with the issuing firm (such as earnings projections, product pipeline and so on) and another part is coming from the market as a whole. As you combine different stocks together, the risk particular to each company—the idiosyncratic risk—washes out, leaving only market risk.

Therefore, the most perfectly diversified stock portfolio will still lose money in a bear market. But it is likely to lose less than its less-well-diversified peers. Although systematic risk is usually discussed with respect to equities, it’s helpful to apply the definition to all investments including putatively riskless fare like money-market funds and U.S. Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS), which face fluctuating interest rates and inflation uncertainty. In fact, unless one’s consumption basket is the same as the Consumer Price Index (CPI), then there are really no riskless investments and systematic risk can truly be seen as inescapable.

The wake of the 2008 crisis saw the proliferation of alternative funds, designed to manage portfolio risk. However, this diversification often comes at a cost that can make these unattractive.

The concept of portfolio diversification has been around for a while. The earliest rigorous example comes to us via Bruno de Finetti (1940), an Italian actuary and statistician who formulated the first function to maximize portfolio return and minimize variance for a given level of risk aversion. Unaware of de Finetti, Harry Markowitz (1952) expanded the problem to include the possibility of securities being correlated with one another. This was an enormous refinement. Indeed, Markowitz’s work forms the basis for most portfolio construction work being done today and his model is, appropriately enough, called the Mean-Variance (MV) model. Mean, in this case, refers to the average or expected return.

An MV-Efficient (MVE) portfolio is one for which no higher level of return can be achieved at the same level of risk (variance). This function is maximized by combining different assets in such a way that there is no better combination. As such, the word diversification is often used as a stand-in for MVE portfolios. But they aren’t the same thing. Note that diversification applies to only the V part of MV, saying nothing about return and, thus, efficiency. Diversification is not, by itself, a desirable characteristic.

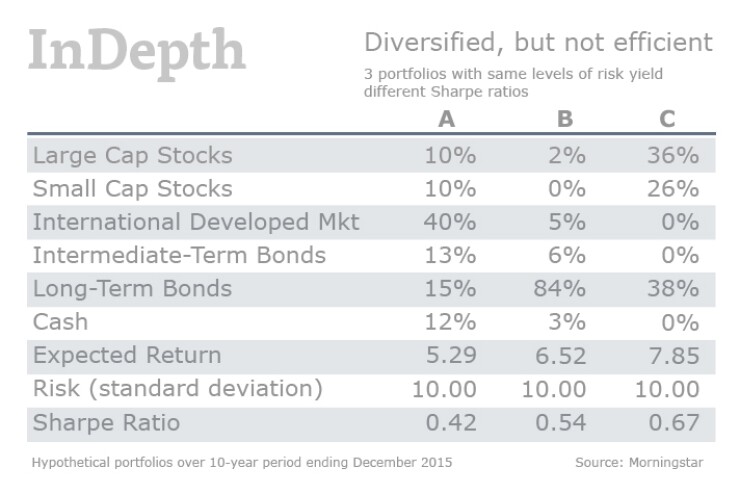

Using returns from the 10-year period ending December 2015, we calculated hypothetical portfolios that appear to be well-diversified but with different Sharpe Ratio, which is the portfolio return in excess of cash, divided by the standard deviation. This is the most common measure of efficiency and the goal is to make this number as high as possible.

Diversification Diversified

The financial crisis of 2008 caused many to rethink the concepts of risk and diversification. Perhaps simply mixing securities to improve non-systematic risk wasn’t enough. Strategies such as risk parity, which seeks to equalize risks across assets, and independent risk allocation, in which portfolios are constructed to minimize the correlation among “statistical” (i.e. non observable) factors driving portfolio performance, became more popular. More recently, economic factor diversification, where diversification is sought through underlying market factors like the value premium and changes in credit spreads, are gaining traction. These represent different ways of defining risk by redefining diversification, more specifically by thinking in terms of the sources of risk and allocating a “risk budget” as opposed to a “capital budget.” In other words, instead of solving for how much to put in each security, we solve for how much to put into each “risk bucket.”

And under each of these definitions, diversification looks different. That is, each could show different levels of risk. This isn't bad, necessarily; it’s just that different portfolios are either diversified or non-diversified under different criteria. Determining what criteria are appropriate for your investment goals is key.

Death and Taxes

Because fees are a component of return, they are vital to efficiency. Like death and taxes, they are inescapable. But like death and taxes they can be managed, or at least reduced in severity. The wake of the 2008 crisis saw the proliferation of numerous alternative funds, designed to manage portfolio risk by creating returns that are loosely correlated with the market. Sadly, the definition of “alternative” is even less agreed upon than that of diversification. It’s been applied to everything from real estate investment trust funds (REITs) to market-neutral funds. The key selling point, however, is that when added to a traditional portfolio, they increase efficiency. However, this diversification often comes at a cost that can make these unattractive. Here at Morningstar, we use category averages and fees for alternative vehicles range from 160 to 225 basis points.

With the category average for intermediate-term bond funds at 81 bps and the average for large-blend funds at 106 bps, this seems steep (to say nothing of index funds). These are for strategies that, for the most part, aren’t designed to produce high long-term returns. For example, the Bear Market category average fee is 196 bps. And this for a fund type that will lose money in the long run. Other strategies, like Market Neutral and Long-Short Equity, were designed for institutional investors and designed to use considerable leverage. But the Investment Company Act of 1940 limits exposure to leverage, and, therefore, cannot be expected to generate returns high enough to justify the nearly 200 bps they typically charge. Leverage does, of course, increase risk considerably, but the chance of making an outsized return can justify the higher fees). An example is in order.

Using historical estimates of U.S. Equity, Government Bond, and Alternative returns, we conducted a Monte Carlo simulation in which we examine the impact of fees on portfolio efficiency as measured by Sharpe Ratio. We began by defining a traditional portfolio of 60% stock and 40% bond and supplement this by adding a representative alternative strategy using data from category averages. We added an alternative strategy to each traditional portfolio at 10%, 25%, and 50% increments. Fixing fees for the traditional portfolio at the category averages (Large-Cap Core and Intermediate-Term Bond), we examined the impact on efficiency for each of our alternative allocations while varying fees from 0 to 2.5%. As the results show, once alternative fees hit 30 bps, a 50% allocation to alternatives cannot be justified. For a 25% allocation, the breakeven point is about 80 bps.

This is an admittedly rough estimate, and 25% and 50% are big allocations. Additionally, alternative allocations are often sourced from bonds (though in this case, that would have made the results look worse) but the point is clear. Diversification cannot be divorced from fees. So diversification and cost are indeed key words for successful investors. But they must be viewed through the lens of efficiency. Alone, diversification and cost mean little.