The March edition of the Journal of Financial Planning had a fascinating article titled, “The Expense-Performance Relationship (or Lack Thereof).” Fascinating for all the wrong reasons.

I read

Both articles claimed that active investing beats passive and that all previous studies on the topic were flawed. According to Nanigian’s work:

- All but the 20% most expensive U.S. equity active funds on average have positive alpha and beat the benchmark (the Wilshire 5000). Index funds also have positive alpha, though smaller than most active funds – a ridiculous assertion, since how can an index fund that tries to own the market beat the market after costs?

- Most modern empirical studies are flawed because they don’t control for the nonlinear relationship between expenses and performance.

- Financial planners mistakenly believe they should search for the lowest-cost funds.

These findings are similar to what Christopher Carosa, a financial writer and editor, concluded in “Passive Investing: The Emperor Exposed,” a 2005 article in the JFP, which won an award before the story had to be retracted. The article had also concluded that active funds bested passive and claimed previous studies were flawed.

Nanigian writes that he is building off a 2005 work by academics Brad Barber, Terrance Odean and Lu Zehng, titled, “Out of Sight, Out of Mind: The Effect of Expenses on Mutual Fund Flows.” Their work examined fund performance from 1970 to 1999; Nanigian used data from Morningstar and looked at net-of-expense returns from 2000 to 2015. He sorted each fund into expense deciles (least to most expensive). He then compared returns of the Wilshire 5000 plus the risk-free rate (one month T-bill) with the average index fund.

Nanigian offered three conclusions. The first was that “2000 to 2015 was a good time to invest in reasonably priced active funds.” The second was that, for all but the 10% most expensive funds, active produced 0.43% annual alpha, more than twice the 0.18% alpha from index funds. Finally, he concluded that the relationships between expenses and performance were weak and nonlinear.

Do these findings make sense? Is Morningstar’s conclusion from its own data that costs matter astonishingly wrong? How can an index fund beat the index after fees? And did Nanigian’s conclusions pass the test of a rigorous review?

QUESTIONING THE RESEARCH

Having spoken to dozens of academics on the costs-performance relationship, I wasn’t quite ready to write off all that work as flawed. I also wasn’t ready to write off Morningstar’s work either, such as the Active/Passive Barometer chart, which shows most active strategies underperformed passive over the past one-, five- and 10-year periods.

I spoke to Nanigian and asked why he hadn’t built in factors such as size and value versus growth. It’s pretty well known that small-cap value stocks as a whole bested large-cap during those 16 years. And I thought every academic and financial planner was aware of the Fama-French three-factor model showing size and value factors, and notes extra return is compensation for additional risk. Apparently, the article compared active to all index funds which, according to Morningstar, would include funds like the ALPS/Sterling ETF Tactical Rotation A (ETRAX) with a 1.72% expense ratio. That’s not what I think of as an index fund.

I noted that alpha must be zero before costs and questioned how the majority of active funds produced positive alpha after costs. Finally, the most baffling finding of all was that index funds bested their benchmarks after costs, creating alpha of their own.

When he was contacted, Nanigian offered to update the study using other factors for an unspecified fee. That offer was rejected. In response, he said that after conferring with “legal counsel,” he would ask Morningstar for research assistance, but only if I and the editors of Financial Planning signed a document stating that we would not disparage him or his analysis; that the agreement would be confidential; and that if he was disparaged he would be entitled to $100,000. That offer also was rejected.

REDOING THE STUDY

I showed the JFP article to David Blanchett, head of retirement research at Morningstar Investment Management. He also had issues with the work and offered to re-create the analysis, taking into account what we felt were shortcomings in the study. Blanchett took these steps:

- In order to separate the impact of expenses from size and value factors, actively managed U.S. equity mutual funds are segregated into the nine domestic Morningstar categories (large/mid/small and growth/core/value).

- Funds within each group were divided into 10 deciles (lowest to highest) based on the annual net expense ratio, netted for distribution fees (for example, 12b-1 fees), for the previous year (this creates 90 total actively managed mutual fund groups that are reconstituted annually).

- Future performance is based on three-year rolling returns, with returns adjusted for distribution fees. Funds with multiple share classes are weighted based on the assets for the month prior to the test period.

- Each fund is grouped by its Morningstar category for December for the month before the test period (for example, funds in the 2010 test year would be grouped based on December 2009 categories).

- All funds are regrouped annually and the dataset is survivorship-bias free. Funds are compared either to a category average, which is the average performance across the 10 deciles, or to a quality index, which is defined as the index funds for each category with the lowest half of expense ratios.

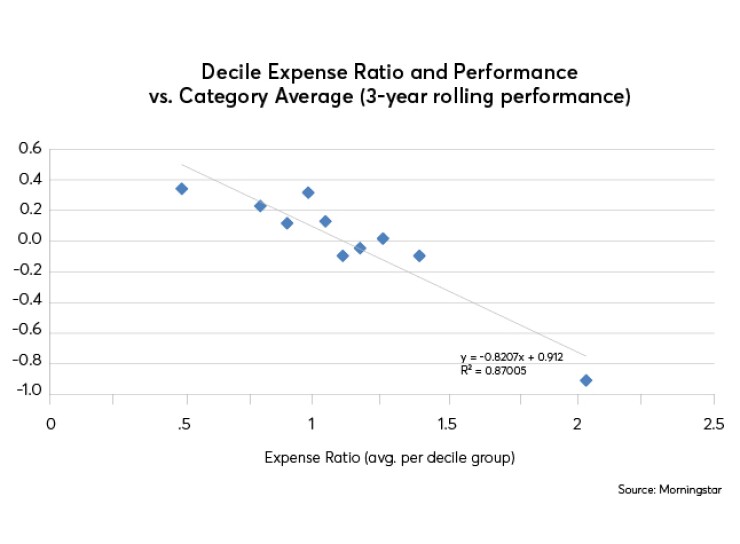

The results are shown below in two graphs. The first compares the returns of each expense decile to the average fund in that category; the second compares returns for each expense decile to the quality index funds (Vanguard-like funds) that would exclude sector rotation index funds with especially high expense ratios. Because expense increases vary greatly by decile (especially for the most expensive decile), the regression to expenses was checked for relationship and linearity.

Blanchett’s analysis showed that active funds underperformed index funds. Even the lowest-cost decile of active funds underperformed index funds; the higher the costs, the larger the shortfall. And the relationship was very linear, with 87.45% of the variation explained by expenses. The same is true with active funds versus the category average. Lower-cost funds perform better than average, while higher-cost funds underperform. Again, the relationship was very linear, with 87% of the variation explained by expenses.

Bottom line: Using the same database and period of time but adding two factors (size and value), benchmarking against only low-cost index funds and looking at three-year performance (rather than one year, which is more consistent with average holding periods) resulted in pretty much the opposite conclusions to the Journal of Financial Planning article. Expenses matter and the relationship is indeed linear.

NANIGIAN RESPONDS

I shared the results with Nanigian, who responded that he did not take into account market factors because they “lack a strong theoretical foundation” and that doing so “would inhibit my readers’ ability to digest my article.” He noted that no factors other than the capital asset pricing model are tested on the CFP exam. He maintained his belief that index funds, in the aggregate, do produce alpha and that this period was a good time to invest in reasonably priced active funds, though he did note that “static factor allocation” is a possible explanation for his results. After weeks of follow-up, Nanigian finally responded that the relationship weakens if decile 10 is excluded – but he did not reply when asked why it should be excluded. Blanchett notes the linear relationship is still strong even if it is excluded.

“Any time you see the top eight deciles of funds besting the benchmark over 16 years, you’ve got to ask if the benchmark is appropriate.”-- Terrance Odean of the University of California at Berkeley

What about the prior work from Barber, Odean and Zheng that Nanigian claims he was building on? When I told Terrance Odean of the University of California at Berkeley about Nanigian’s study and the updated work from Morningstar, he said, “Any time you see the top eight deciles of funds besting the benchmark over 16 years, you’ve got to ask if the benchmark is appropriate.” While not reviewing or endorsing the Morningstar work, he said the regressions “look pretty linear to me” and added: “I’m quite comfortable recommending low-cost, well-diversified index funds to most investors.”

In my view, both Nanigian’s article and the award-winning-then-retracted Emperor Exposed piece a decade earlier had much more in common than the conclusions that active funds beat passive. The methodologies were badly flawed, the data providers disagreed with the methodology and the responses from the authors were telling. In the case of the piece from a decade ago, it survived an anonymous JFP appeals committee challenge from me; the committee refused to check with Lipper, the data provider. Only after being asked in writing why they had not checked with Lipper did the JFP do so and soon after retract the piece.

What does this say about the editorial standards of the JFP and its parent, the Financial Planning Association? How can this be consistent with the FPA’s statement that it “supports high standards of professional competence, ethical conduct and clear, complete disclosure when serving clients?”

When Nanigian stopped responding to my inquiries, I spoke with the Journal editor, Carly Schulaka, who said, “It does not concern me that he has not responded to your most recent question.” Regarding my concerns about the article’s conclusions, she said, “Healthy debate on the relationship between mutual fund performance and expenses will continue to build the body of knowledge.”

Financial planners deserve thought-provoking analysis, but if we rely on work that does not have the thorough review that’s necessary, we can harm our clients and unthinkingly violate the high standards the FPA talks about.

Will I formally challenge this piece? No, because my concern involves more than one article. Rather, I wonder about the JFP review process and how it has stumbled badly twice on the same topic.

Schulaka, who was not editor at the time of the 2005 retraction, said: “No editorial or peer review process is perfect. We continually strive to provide the most accurate, informative, applicable, innovative and thought-provoking content possible. The column by Nanigian published in the March 2016 issue was editorially reviewed. In this particular instance, neither our volunteer academic editor nor volunteer practitioner editor were involved in that review. As editor, I approved the column for publication.” She added: “Should you wish to submit an article to the Journal, explaining to readers why you think David Nanigian’s methodology was flawed, we would be happy to consider it.”

In just over a decade, two articles implying we live in Lake Wobegon, where most funds are above average, made it through the JFP review process. Financial planners deserve thought-provoking analysis, but if we rely on work that does not have the thorough review that’s necessary, we can harm our clients and unthinkingly violate the high standards the FPA talks about.