Morgan Stanley's annual "State of the States" webinar is usually a pretty staid tour of state balance sheets. This year, though, it drew more than double the usual audience and more than six times typical registration as financial advisors clamored for a chance to ask questions about what President Donald Trump's agenda means for municipal budgets — and the bonds tied to them.

They wanted to know which states are most exposed to delays in federal funding, how quickly that would affect budget decisions, and if new funding policies will hurt credit quality for certain municipal debt.

Craig Brandon, Morgan Stanley Investment Management's co-head of municipals, said many questions came in at the event late last month about the biggest blue-state bond issuers in the market, including California, New York, Illinois and New Jersey, amid a series of recent federal funding freezes and threats.

"The president clearly goes after the blue states, and the way he goes after them is through funding," Brandon said in an interview this week. "We don't think it's a major credit risk, but it's natural for financial advisors to have these questions when it's in the headlines."

READ MORE:

The concerns are driven less by a single policy change than by a pattern that can create real uncertainty for budget writers: federal dollars appear to be on hold, then are suddenly released — or cut — leaving states to bridge the gap in the meantime.

In New York and New Jersey, work on the $16 billion Gateway rail tunnel under the Hudson River is set to restart next week after the states sued the Trump administration to release frozen funds, underscoring how quickly reimbursement interruptions can spill into major infrastructure projects. Federal health officials are also preparing to cut about $600 million in public-health grants to California, Minnesota, Illinois and Colorado, while five Democratic-led states have sued to block attempts to freeze $10 billion in child care and family aid funding. Trump has also repeatedly vowed to yank dollars from so-called sanctuary cities, but judges have barred the administration from following through.

That kind of stop-and-go federal support is now showing up directly in budget season. New York Gov. Kathy Hochul last month rolled out a roughly $260 billion budget without raising personal income or corporate tax rates, helped by stronger-than-expected tax receipts. But she warned the state's "fluctuating fiscal relationship" with the federal government is creating new risks.

READ MORE:

"For decades, there was always this basic trust," Hochul said at the time. "In just one year, the Trump administration has shattered that trust and we're bearing the brunt of it."

Even with the heightened attention, Brandon said he hasn't seen the anxiety translate into broad muni-market moves — including in California, which drew the most questions about whether political conflict could threaten the state's debt.

"There are clearly questions, but it doesn't really seem to be impacting flows. There are no signs that people are selling California bonds," he said. "It's the opposite. There's still more demand for California bonds than the supply that exists."

Brandon said his team still views state credit as generally steady, with many governments starting the year with healthy reserves and debt loads that look manageable. Stronger economic growth, solid market returns and pension changes have helped bring down states' typical debt and pension burdens from earlier highs, he said, and rainy-day funds are still near record levels on average. But looming risks including tariff policies, wealth movement between states and curtailed federal support could squeeze budgets in the future.

The pressure point, Brandon said, is that many budgets are now staring at less federal support for Medicaid and the supplemental nutrition assistance program after Trump's

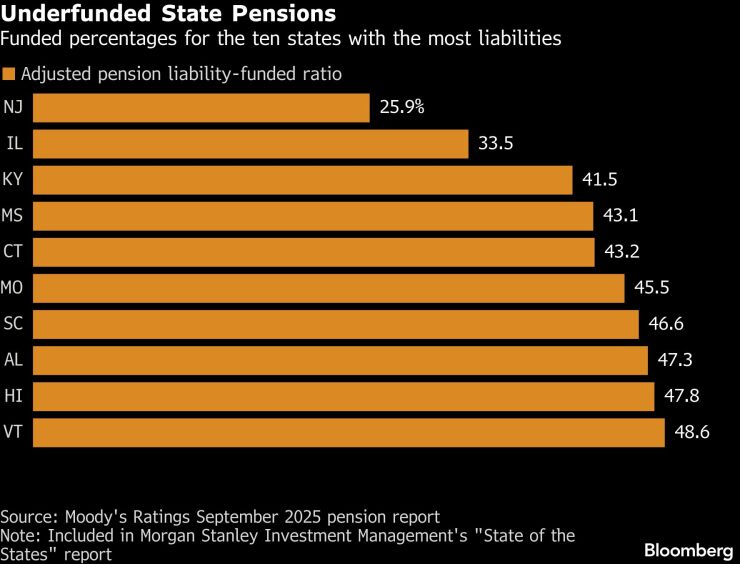

If states choose to plug those holes, Brandon said, that can jeopardize other priorities, including pension catch-up payments. Morgan Stanley's rankings put Illinois, New Jersey and Kentucky at the bottom, and he noted all three carry heavy obligations to the retirement systems that pay benefits to government workers.

"But making a higher pension payment forces you to underfund something else, at a time when the federal government is cutting SNAP and Medicaid," Brandon said. "How long can you try to catch up on your pension when you have to divert that money to try and do something else?"

Brandon also pointed to the ripple effects for muni investors beyond state general obligation debt. Even if most states remain on solid footing, tighter budgets can squeeze issuers that depend on state appropriations — including city governments, hospitals and colleges and universities.

"The states impact so many other sectors out there," he said. "When they struggle, there's a trickle-down effect."