Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

On March 11, President Biden signed the

For individuals with more modest incomes, there is essentially no planning needed to ensure the maximum 2021 recovery rebate amount is received. In fact, in many cases, taxpayers will have already received such amounts from the IRS as a prepaid credit in the form of a stimulus 'check' (which may be in the form of an actual check, direct deposit, or debit card).

In other situations, however, having had higher income in previous years may prevent a taxpayer from receiving a stimulus payment now. And the same may ultimately prove true for 2021's income when they file their return next year, regardless of whatever actions they take in the interim.

There are, however, a non-trivial number of individuals who can take action during 2021 that will enable them to receive a (larger) 2021 recovery rebate, either now or when they file their 2021 income tax return. And with these rebates being (potentially) the largest yet, advisors need to pay more attention to recovery rebate-increasing strategies than ever before.

Determining the maximum recovery rebate potentially due for a taxpayer

The maximum potential amount of an individual's 2021 recovery rebate is determined by multiplying $1,400 times the number of eligible individuals. Eligible individuals include the taxpayer(s) themselves (so $1,400 for Single filers and $1,400 × 2 = $2,800 for Joint filers), as well as any dependents claimed by the taxpayer.

Example #1a: Inez is a married taxpayer who files a separate return from her spouse (Married Filing Separate). Inez has two children, both of whom she claims as dependents.

Accordingly, Inez's maximum potential recovery rebate is 3 (counting Inez herself and her two children) × $1,400 = $4,200.

One important difference between the stimulus payments authorized in 2020 (under both the

Notably, because all dependents are eligible — not just qualifying children — those who are taking care of (and claiming a dependent exemption for) their parents can also ‘earn’ a recovery rebate for them.

Example #1b: Edmund is a single taxpayer who lives with and takes care of his elderly father, whom he claims as a dependent.

Accordingly, Edmund’s maximum potential recovery rebate is 2 (counting Edmund himself and his dependent father) × $1,400 = $2,800.

Recovery rebate phaseouts based on AGI

It's important for advisors to realize that there is often a difference between an individual's maximum potential recovery rebate and the actual recovery rebate that they will receive. The reason is that 2021 recovery rebates are phased out as a taxpayer's income exceeds their applicable income threshold.

And unlike the gradual phaseout of

The AGI phaseout ranges are as follows:

- Single filers and married filing separate: $75,000 – $80,000

- Head of household: $112,500 – $120,000

- Married filing joint: $150,000 – $160,000

Example #2: Lynn and Bud file a joint return and have two dependent children. Their maximum potential 2021 recovery rebate is 4 (for Lynn, Bud, and their two kids) x $1,400 = $5,600.

Lynn and Bud have a total AGI of $150,000. Since their AGI is not more than the $150,000 lower end of their applicable phaseout range, they would be entitled to their full $5,600 maximum 2021 recovery rebate.

However, if the couple sold an investment and had $7,000 of capital gains right before the end of the year, their total income would increase to $157,000. Just that additional $7,000 of income would put them 70% of the way through their $10,000 phaseout range of $150,000 – $160,000.

Accordingly, Lynn and Bud will have 70% × $5,600 = $3,920 of their 2021 recovery rebate phased out, leaving them with only a $1,680 2021 recovery rebate. Which means just $7,000 of income cost the couple $3,920 of their recovery rebate.

And, of course, with just $3,000 more of income, Lynn and Bud would be phased out of all $5,600 of their 2021 recovery rebate altogether.

2021 recovery rebates may be received based on information reported on 2019, 2020, or 2021 income tax returns

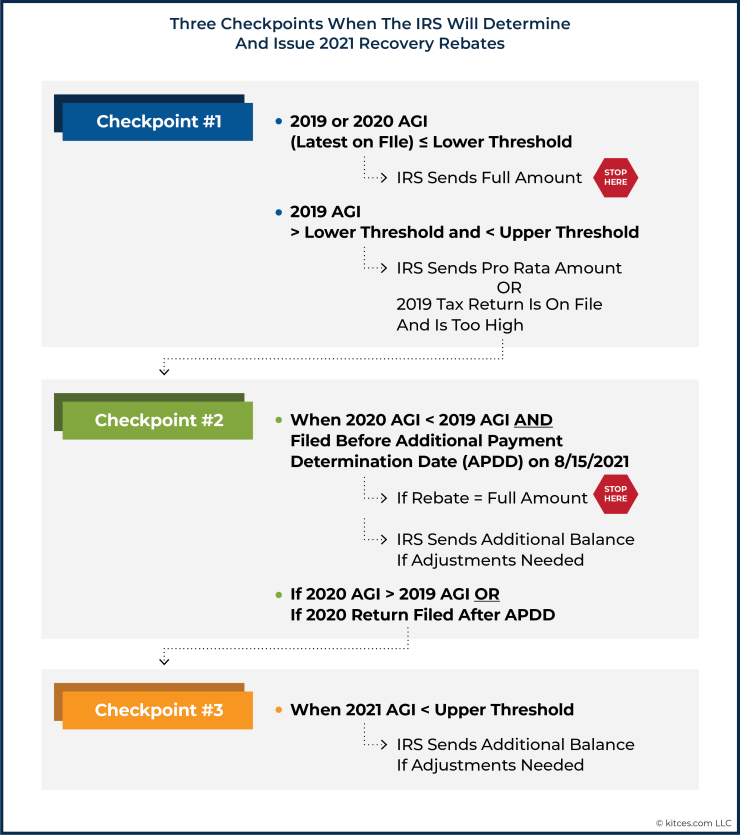

One of the most confusing aspects of 2021 recovery rebates is that there's the potential for an individual to receive the amount based on their 2019 income, their 2020 income, or their 2021 income. That's because, similar to the

Given that the American Recovery Plan was enacted on March 11 (less than one month after the start of a delayed 2021 tax season on Feb. 18, and well before the delayed 2020 tax filing deadline on May 17), for most taxpayers, the most recent AGI on file at the time the IRS first issued advance payments of 2021 recovery rebates was the taxpayer's 2019 AGI (though 2020 tax returns were already on file for some early filers).

To the extent that an individual's 2019 AGI was below the phaseout range, these taxpayers generally should have received their 2021 recovery rebates already, and no further 2021 recovery rebate credit planning is necessary.

But for many whose AGI on file with the IRS at the time of enactment (either from their 2019 tax return or their early-filed 2020 return) was too high to qualify for the maximum 2021 recovery rebate credit, ARPA provides for at least a second chance, and in many cases, both a second and a third chance, to receive the (maximum) credit.

Specifically, for the majority of individuals who had not yet filed their 2020 tax return at the time the IRS first processed 2021 recovery rebate credits, the American Recovery Act offers a second opportunity to receive the credit in advance (as a stimulus check instead of as a credit on the 2021 tax return), based on the taxpayer's 2020 AGI, provided their 2020 tax return is filed before the Additional Payment Determination date, which is the earlier of:

- 90 days after the 2020 calendar year filing deadline (90 days after the current filing deadline of May 17 is Aug. 15. Aug. 15 is a Sunday, and it’s not yet clear whether the IRS will view that date, or Mon., Aug. 16, as the additional payment date);

- or Sept. 1

To the extent that a taxpayer's 2020 return is filed before this deadline, and the income on that return is low enough to create a larger 2021 recovery rebate credit than what the taxpayer qualified for originally, based on their 2019 AGI, the IRS will send a stimulus check to make up the difference (which if the recovery rebate was fully phased initially based on 2019’s AGI, could simply be the full recovery rebate if 2020’s AGI was under the income phase out limit).

Finally, for those who (will) have not yet received their maximum 2021 recovery rebate credit amount, the filing of their 2021 tax return will represent the last opportunity to receive any remaining credit amount. To the extent that the AGI reported on the 2021 return is low enough to create a larger 2021 recovery rebate Credit than what the taxpayer has already received (based on their 2019 and/or 2020 AGI), the taxpayer will be 'trued up' via a credit (versus an additional stimulus check) on their 2021 income tax return.

Example #3: Recall Lynn and Bud from Example #2, who file a joint return, have two dependent children, and have a maximum potential 2021 recovery rebate of $5,600.

As illustrated in Example #2, at $157,000 of AGI, the couple was 70% × $5,600 = $3,920 phased out of their maximum 2021 recovery rebate, leaving them with only a $1,680 2021 recovery rebate.

Suppose that the $157,000 of AGI was the couple's 2019 AGI. And further suppose that Lynn and Bud file their 2020 income tax return before the Additional Payment Determination Date, reporting $145,000 of AGI for 2020.

Since $145,000 of AGI is below the couple's 2021 recovery rebate phaseout threshold, the IRS will process an additional payment amount of $5,600 – $1,680 = $3,920, equal to the difference between the amount the couple received initially based on their 2019 AGI, and the amount to which they were entitled based on their 2020 AGI.

Critically, as was the case with the 2020 recovery rebate credits authorized by the

In other words, if a taxpayer received a 2021 recovery rebate credit based on their 2019 AGI, having a higher AGI in 2020 and/or 2021 will not result in the loss of that credit, nor a requirement to pay any amount back.

Similarly, if a taxpayer received a 2021 recovery rebate credit based on their 2020 AGI, receiving a higher AGI in 2021 will not result in the loss of that credit, nor a requirement to pay any amount back.

In short, with proper planning, a taxpayer can receive the maximum 2021 recovery rebate credit if their AGI in just any single year between 2019 and 2021 was/is below their applicable phaseout range.

Taxpayer strategies to increase 2021 recovery rebate credits

While 2019 is behind us, individuals who have not yet received a full 2021 recovery rebate credit still have the ability to take action(s) now to try to increase the credit amount based on their 2020 or 2021 AGI. Below are some strategies that can help.

Be mindful of the additional payment determination date

Each year, millions of taxpayers file

For many, however, Aug. 16, should be viewed as the de facto filing deadline for 2020 income tax returns.

Recall that under ARPA, individuals who received less than their maximum potential recovery rebate check amount based on their 2019 AGI can use their 2020 AGI to qualify for a larger 2021 recovery rebate credit, but only if they file their return before the additional payment determination date. And that additional payment determination date is the earlier of 90 days after the 2020 calendar year filing deadline or Sept. 1, 2021.

Notably, in March, the IRS postponed the 'original' filing deadline for 2020 income tax returns from April 15, 2021, to May 17, 2021. Ninety days after the May 17 deadline is Aug. 15, which falls on a Sunday. Accordingly, the next business day, Aug. 16 (which, after consulting the calendar, appears to fall before Sept. 1), is the additional payment determination date.

It's no secret that 2020 was a rough year for many individuals. Unemployment rolls hit historic highs, millions of workers had hours or pay reduced, and countless business owners saw revenues and profits evaporate as the pandemic's impact was felt. And while things haven't quite returned to normal yet, 2021 is certainly off to a much better start than 2020.

As a result, for many taxpayers, 2020 will represent a blip on the radar and a uniquely low-income year… and perhaps the only year in which their income will be low enough to allow them to qualify for any (if not the maximum) amount of 2021 recovery rebate credit.

In such circumstances, Aug.16 really needs to be viewed as the taxpayer's drop-dead date to file their 2020 income tax return in order to have their (lower-in-2020) income count towards qualifying for a 2020 recovery rebate. As despite still having roughly another two months to file 2020 income tax returns ‘on-time', any AGI reported after the additional payment determination date will be disregarded for purposes of calculating the recovery rebate credit amount, potentially eliminating the chance of ever receiving such a credit.

Reduce 2020 income by exploring all available options

2020 is behind us (thankfully), but that doesn't mean a financial advisor's ability to manage a client's 2020 income has totally passed us by. Rather, while there's not an extensive list of post-year-end ways of reducing income, we're still early enough in 2021 that a few options remain.

To the extent that such actions can reduce a taxpayer's income low enough to provide for a larger 2021 recovery rebate credit amount — i.e., by reducing income within or below the phaseout range — they should be explored.

Commonly available options to reduce 2020 AGI include the following:

- Deductible traditional IRA contributions. Perhaps the most obvious way to reduce 2020 income now is via a deductible Traditional IRA contribution. Single taxpayers who are eligible to make such a contribution, but have not yet done so, can reduce their 2020 AGI by up to $6,000 (or $7,000 if they were 50 or over by the end of 2020), and married couples filing joint returns can reduce their 2020 AGI by up to $12,000 (or $14,000 if both individuals were 50 or over by the end of 2020).

2020 Traditional IRA contributions can be made up through the May 17, postponed initial filing deadline.

- Deductible HSA contributions. Like IRA contributions, HSA contributions for 2020 can be made up through May 17. Accordingly, if an individual had an HSA-eligible high-deductible health plan in 2020 but has not yet made a full contribution for the year, there's still time to fill up the HSA deduction 'bucket.'

The HSA contribution limit for 2020 is $3,550 for self-only coverage and $7,100 for family coverage. An extra $1,000 can be contributed as a catch-up contribution if the taxpayer was 55 or older at the end of 2020, and an additional $2,000 (total) can be contributed if both the taxpayer and their spouse were covered by an HSA-eligible high-deductible health plan and were age 55 or older at the end of the year (though the $2,000 total amount must be split evenly, with $1,000 being contributed to each spouse's HSA account).

- Don't opt out of the installment method of reporting sales. To the extent that someone sold eligible property in 2020 and will be receiving payments for that property over two or more tax years, the default method of reporting the gain from such a sale is the installment method.

The installment method allows for the gain from such a sale to be reported ratably as payments are received. While long-term capital gains benefit from preferential tax rates, they add to AGI (and thus may contribute to reducing or eliminating the 2021 recovery rebate altogether) in the same manner as ordinary income. Accordingly, spreading gain from such sales over multiple years, instead of reporting it all in 2020, can help to mitigate any reduction of the taxpayer's 2021 recovery rebate credit.

Small business owners also have a few specific considerations that can help them increase their chances at a larger recovery rebate check:

- Employer-funded retirement plans. Individuals who own a small business may have additional flexibility with respect to using retirement account contributions to lower their 2020 AGI enough to qualify for a recovery rebate. And, thanks to

changes made by the SECURE Act in December 2019 , first effective for the 2020 tax year, there are more options than ever to choose from.

More specifically, while some retirement plans must be established and/or funded by year-end (i.e., last Dec. 31), business owners may adopt and/or fund any of the following retirement plans through their business' filing deadline, including extensions (making them still available to reduce AGI):

- SEP IRA

- Profit-Sharing Plan

- Pension Plan

- Annuity Purchase Plan

- Depreciation elections. Some business owners may have an additional opportunity to reduce 2020 income by making certain elections to depreciate certain property acquired during the year faster than usual.

For instance, the 100% additional first-year depreciation deduction created by

Manage 2021 income proactively to maximize recovery rebates

For individuals who are not able to receive the maximum recovery rebate credit based on their 2019 and/or 2020 tax return AGI, 2021 represents a final chance to get AGI low enough in order to receive that amount.

Notably, taxpayers can try to minimize their 2021 AGI using all of the methods discussed above to potentially reduce 2020 AGI, such as deductible IRA contributions, HSA contributions, and accelerated depreciation elections.

But, we're still in 2021, which means there are a lot more options and tools to proactively keep income low enough in order to qualify for the maximum 2021 recovery rebate credit. Accordingly, advisors can consider the following when discussing how clients can maximize their 2021 recovery rebate credit by getting under the AGI phaseout threshold:

- Can year-end bonuses be delayed until 2022? While employees may receive bonuses at various times throughout the year, one of the most common times for a business to pay bonuses is late in the year, around holiday time.

To the extent that such a bonus would increase an individual's AGI enough to reduce or eliminate an otherwise available 2021 recovery rebate credit, they may consider asking if their employer would be willing to hold off on paying the bonus until early 2022 instead.

Certainly, not all employers will accommodate such requests. But employees will never know unless they try, right?

- Cash-basis business owners often have increased flexibility. When an individual owns a cash-basis business, they can often exercise a significant amount of influence over their personal AGI by deciding whether certain business expenses get paid late in the current year or early in the following year. Naturally, by accelerating expenses into 2021 (to the extent possible), 2021 income will be lowered, potentially allowing them to receive a larger 2021 recovery rebate credit.

Additionally, to the extent they can afford to do so, cash-basis business owners may consider delaying billing for services or products provided late in the year until early 2022 (provided, of course, they are confident they will still be able to collect such payments).

Just how far a business owner will be able to push this strategy will vary depending upon how long the business owner can continue to pay necessary expenses of the business (and potentially support/pay themselves). In certain cases, a business owner may only be able to go a few weeks without billing before they get into cash-flow trouble, while in other circumstances, a business owner may be able to delay billing for several months or even longer.

Ultimately, cash-basis business owners whose AGI is even remotely close to their applicable phaseout threshold may be able to use cash-flow tactics like these to help drive income low enough to qualify for a 2021 recovery rebate credit (or at least low enough to allow for other measures, such as retirement account contributions to get them there when they otherwise would not).

- Take an unpaid leave of absence. A pretty unique and somewhat unorthodox planning strategy that may help some taxpayers qualify for a higher 2021 recovery rebate Credit is to consider taking an extended, unpaid leave of absence from employment. As recovery rebates are large enough that for those earning 'moderate' income, giving up as much as one to two months of salary could still be less than what is received back in recovery rebate credits.

Of course, not all employers will allow for such extended breaks, but, again, it can't hurt to ask.

Notably, even in cases where the loss of income from an unpaid leave of absence may be more than any increase in an individual's 2021 recovery rebate credit amount, the difference may be small enough to make the extended 'vacation' worth it anyway.

Example #4: Buzz and Sue are married and file a joint income tax return. They have three children whom they claim as dependents, making their maximum 2021 recovery rebate credit amount 5 × $1,400 = $7,000.

Both Buzz and Sue are salaried workers of a local town who are covered by the town's pension program, so they are phased out of making deductible IRA contributions. Buzz has an annual salary of $100,000, and Sue has an annual salary of $60,000. Neither has received a raise since the beginning of 2019.

The couple is not eligible for any above-the-line deductions. Accordingly, their AGI in both 2019 and 2020 was exactly $160,000, just enough to completely phase them out of receiving a 2021 recovery rebate credit. Barring any additional actions, their 2021 AGI will be the same $160,000, once again preventing them from receiving any 2021 recovery rebate credit.

Suppose, however, that Sue was able to speak with her supervisor and arrange for a two-month unpaid sabbatical for November and December 2021. Based on Sue’s annualized salary of $60,000 per year, her total compensation for 2021 would be reduced by [$60,000 ÷ 12 = $5,000] ×2 months = $10,000, giving a total 2021 compensation of $50,000. Added to Buzz's salary of $100,000, the couple's combined AGI for 2021 would be $150,000.

That $150,000 would be just low enough to entitle the couple to receive their maximum recovery rebate amount of $7,000 (as a credit on their 2021 income tax return), thereby blunting the blow of Sue's $10,000 loss of income. But that's not all…

While the recovery rebate of $7,000 is nontaxable, the $10,000 of income that Sue would have earned, had she not taken a two-month unpaid sabbatical, would have been taxable. So, by not working those two months, the $10,000 less in income earned also saved the couple an additional $10,000 × 22% = $2,200 of tax liability.

Accordingly, the net-after-tax impact of Sue’s two-month sabbatical would be just $10,000 (lost income) – $2,200 (tax savings) – $7,000 (total recovery rebate amount) = $800 of foregone salary for 2 months of leave.

How many clients wouldn't take that trade (and hug you for suggesting it)?

- Be mindful of 2021 Roth conversions and other retirement account distributions. Advisors should be sure to review any plans for 2021

Roth conversions to see if they might impact a client's ability to claim a 2021 recovery rebate credit. To the extent that such a conversion would prevent the client from receiving their maximum recovery rebate credit amount, the conversion should be reevaluated to calculate the true marginal cost/rate (taking into account any loss of the 2021 recovery rebate credit) to determine whether it makes sense to proceed with the conversion, as planned.

Similarly,

- Be mindful of 2021 portfolio income. Advisors who have clients trying to keep 2021 AGI low enough to qualify for a (larger) 2021 recovery rebate credit should also be mindful of any portfolio income that the client may generate.

-

Biden’s proposal to raise capital gains taxes on investments profits would hit many business owners, not just ultra-wealthy investors.

April 27 -

If passed, the package would end the step-up in basis provision, which will mean significantly larger tax bills for wealthy estates.

April 27 -

Advisors who leave wirehouses face key tax considerations to become successful RIAs.

April 23

Capital gains should be carefully managed to not push investors over the recovery rebate phaseout thresholds, and to the extent that a client has unrealized losses, advisors can help clients minimize their AGI by capitalizing on the (realized) net capital losses (up to $3,000) that can be used to offset ordinary income each year.

Positions or other investments yielding significant amounts of dividends and/or interest should be reviewed to determine whether they should be temporarily reallocated to investments that may not impact AGI as much (such as swapping dividend-producing investments for growth investments or swapping interest-producing investments for municipal bond funds). Of course, any capital gain that may result from any of those reallocations must also be considered.

Finally, it's worth noting that taxpayers whose AGIs are particularly close to the phaseout range should pay particular attention to year-end capital gains distributions for any mutual funds held in taxable accounts; such distributions could push individuals above their applicable phaseout and reduce (or eliminate) an otherwise allowable 2021 recovery rebate credit.

Explore whether filing separate returns can benefit married taxpayers

Married couples may have an additional lever to pull to help them get a larger 2021 recovery rebate credit. More specifically, married couples may wish to explore whether filing separate tax returns may entitle them to (a larger) 2021 recovery rebate credit.

Of course, there's a reason that married couples generally don't file separate returns and tend to file jointly. In short, married individuals who file separate returns are 'stuck' using tax brackets that may not be as favorable, particularly if one individual earns a majority of the couple's income. In addition, married couples who file separate returns are prohibited from claiming a number of popular tax benefits.

Nevertheless, in the right circumstances, filing separate returns can allow the lower-earning spouse to claim a 2021 recovery rebate credit that is large enough to more than make up for the loss of any other tax benefits and/or the less favorable married filing separate brackets. Here's the gist of this strategy in a nutshell…

Instead of filing a joint return, a married couple files separate returns, and the individual with less income claims all of the children eligible to be claimed as dependents on their income tax return. Provided the lower-earning spouse's AGI is below the phaseout range ($75,000 - $80,000), they can receive the full 2021 recovery rebate credit amount. And if that amount is large enough, it can make filing separate the net tax-savings strategy (even with otherwise unfavorable tax brackets for married couples filing separately).

Example #5: Johnny and Lana are married taxpayers who live in a separate property state with three children, all of whom they claim as dependents. Johnny earns $200,000 per year, and Lana earns $50,000 a year.

Accordingly, their $250,000 combined income completely phases them out of claiming any 2021 recovery rebate credit amounts on their 2021 jointly filed tax return.

Assuming the couple claims the Standard Deduction, their tax liability for 2021 would be $42,018.

But what if Johnny and Lana were to file separate returns?

At first glance, this may not appear like a particularly good move. After all, if they were to file separately, Johnny would have a tax liability of $40,811 on his $200,000 of income, while Lana would have a tax liability of $4,295 on her $50,000 of income. Their combined $45,106 tax bill filing separately would be $3,088 more than their tax liability filing a joint return due to the less-favorable tax brackets that apply when filing separately.

But a closer look reveals that Lana's AGI is now below the $75,000 threshold where the 2021 recovery rebate credit amount begins to phase out. Accordingly, Johnny and Lana can 'stuff' Lana's separate return with all three of their children as dependents.

The end result?

Lana ends up with a 2021 recovery rebate credit of $5,600 on her 2021 income tax return, providing a net gain of $5,600 (Rebate Credit amount) – $3,088 (additional tax liability of filing separately relative to filing jointly) = $2,512 of tax savings, after accounting for the increased combined tax liability associated with the separate returns and the recovery rebate credit that Lana would receive.

Notably, this type of 'dependent stuffing' is possible when the dependents are Qualifying Children, even when the higher-earning spouse provides more support for the children claimed as dependents on the lower-earning spouse's separate return. In fact, the lower-earning spouse could even earn $0 and technically provide no support (at least as far as the Internal Revenue Code is concerned) for the Qualifying Children dependents.

More specifically,

There is seemingly an endless number of variables to consider when trying to identify married clients for whom separately filed returns will provide a net-positive benefit. Thankfully, though, advisors can use a few short-hand rules to help them winnow down the list of clients most likely to benefit from exploring the approach.

Rule #1: Lower-earning spouse's AGI must be below the phaseout range

The whole point of the strategy of a married couple filing separately is to try to split a joint return into two separate returns to produce a 2021 recovery rebate credit amount on the lower earner's return that is large enough to offset any increase in tax that the couple, as a whole, is likely to encounter as a result of filing separate returns.

But if the lower-earning spouse's AGI is above the married-filing-separate phaseout range, they won't receive any 2021 recovery rebate Credit, regardless of how many dependents they claim. That would make this approach a non-starter (at least for purposes of maximizing the 2021 recovery rebate credit).

Rule #2: The closer the lower-earning spouse's income is to the phaseout range, the better

When it comes to trying to determine if a married couple may benefit from filing separate returns due to an increased 2021 recovery rebate credit, the higher the lower-earning spouse's AGI is, the better … but only to a point. You might think of it like a weird game of tax 'chicken,' where the goal is for the lower-earning spouse's AGI to be as high as possible, but per Rule #1, not so high as to cause them to be phased out of the credit to begin with.

So, why do we want the lower-earning spouse's income to be as close as possible to the phaseout range (without going over)? Simply put, as shown in the chart below, the tax brackets for married couples who file separate tax returns are exactly half that of married couples who file joint returns.

Thus, the greater the percentage of the couple's total income that is attributable to the lower-earning spouse, the more of the couple's collective income that will be taxed at lower rates and, conversely, the less of the couple's collective income that will fall into the higher-earning spouse's higher, less-favorable tax brackets. So, the more evenly the couple's income is split, the less the couple is impacted by the married filing separate brackets. In fact, at perfectly split income, it would seem as if they were using the married filing joint brackets (though other tax benefits may still be phased out).

The table below can be used to easily see this phenomenon in action. Note that in each situation, as the lower-earning spouse's income rises, the couple's cumulative tax bill (before credits) filing separate returns decreases and becomes closer to the tax bill owed filing a joint return (also before credits).

Rule #3: The more dependents that can be claimed, the better

As illustrated above, filing separate tax returns will generally increase a couple's cumulative tax bill as compared to filing a joint return. The hope, though, is that by filing separate tax returns, the lower-earning spouse will be able to receive a 2021 recovery credit large enough to more than offset the increased tax bill.

As noted earlier, the maximum 2021 recovery rebate to which an individual is entitled is equal to $1,400 multiplied by the number of the eligible individuals, which includes the taxpayer and any qualified dependents. Accordingly, the greater the number of individuals the lower-earning taxpayer can claim as dependents on their separate return, the greater the potential 2021 recovery rebate (and the larger the disparity between filing joint and separate returns can still potentially make sense).

The highlighted column in the table below illustrates how many individuals, including the taxpayer, it would take to produce a 2021 recovery rebate credit large enough to bridge the gap between the tax bills created by filing a joint return versus separate returns (and assuming that there are no additional preparation fees for filing separately relative to a jointly filed return).

So, for instance, a married couple with $200,000 of cumulative AGI, split $150,000 for spouse one and $50,000 for spouse two, would have a tax liability of $31,304, which is $1,286 more than the tax liability of filing jointly. However, if the spouse with $50,000 'earned' a recovery rebate for $1,400 (with no dependents), it would more than make up for the additional tax created by filing separate returns.

By contrast, if the higher-earning spouse earned the full $200,000, it would take the lower-earning spouse plus at least seven additional dependents to create a 2021 recovery rebate credit large enough to make up for the additional tax of $10,793 created by filing separate returns, since 8 (1 taxpayer + 7 dependents) x $1,400 = $11,200.

Of course, while filing separate returns can enable the lower-earning spouse to claim a recovery rebate credit when none might otherwise be available, they might also lose out on other tax benefits. To that end …

Rule #4: The less a taxpayer would benefit from the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (and other tax benefits lost filing separate returns), the better

One of the most common (and most valuable) tax benefits that is not available to married individuals who file separate income tax returns is the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC). The loss of this credit has been meaningful in most years past, but never before has it been as potentially valuable as it is in 2021.

The reason is that

Missing out on credits that large, coupled with an already-higher tax bill as a result of filing separately, would make it exceedingly difficult to generate a 2021 recovery rebate credit large enough to make filing separate returns a net-tax-reducing strategy.

Of course, the CDCTC is far from the only tax benefit married couples who file separate returns are ineligible to receive. Other tax benefits that fall into this category (unable to be used by married couples filing separate returns) include the following:

- Education credits (both the American Opportunity Tax Credit and the Lifetime Learning Tax Credit)

- Earned Income Tax Credit

- Student Loan Interest Deduction

- Interest from qualified U.S. savings bonds used for qualified higher education expenses

In addition, many other tax benefits can be reduced or eliminated due to (sometimes much) lower phaseout ranges applying to married individuals who file separate returns.

Identify potential couples now to take meaningful action in 2021

It would be easy for an advisor to consider strategies to maximize a client's recovery rebate credit and think to themselves, "Well, we'll just look at this with the client's CPA or other tax professional when they file their return next year." But waiting until next year could prove to be a costly decision.

For instance, identifying the married filing separate strategy as a potential solution now can provide time to transfer assets in advance from an account owned by one spouse (or jointly by both spouses) to an account in the other spouse's name. Transferring income-producing assets out of a lower-earning spouse's account and into the account of a higher-earning spouse could enable the lower-earning spouse to get below the phaseout limit, thereby entitling them to a 2021 recovery rebate credit in the first place.

By contrast, shifting assets out of a higher-earning spouse's account and into the account of a lower-earning spouse could enable the couple to more evenly split income, thereby reducing their combined tax bill when filing separate returns.

Although each situation is different, married clients most likely to benefit from filing separate returns are those clients with cumulative AGI above $150,000 and below $300,000, where the lower-earning spouse is below the phaseout range. The more dependents the client has, the better. And the closer the lower-earning spouse is to the phaseout range (without going over), the better as well.

The 2021 recovery rebates authorized by ARPA represent a non-trivial amount of money for many individuals. At a maximum of $1,400 per eligible individual (taxpayers plus any dependents), the maximum amount of one's 2021 recovery rebate credit can quickly add up.

Strategies that advisors can use to help their clients receive the highest recovery rebate credit possible include ensuring those with temporarily low income in 2020 file their 2020 returns by the Additional Payment Determination Date, using tax-deductible contributions and tax elections to help reduce 2020 income further, proactively managing 2021's income, and exploring whether filing separate returns provide a net benefit to married taxpayers.

While some taxpayers will have either past or current income that is low enough to enable them to receive the maximum recovery rebate amount with no further action, others will earn too much to claim any credit amount no matter what strategies they employ. But for a number of individuals whose incomes are closer to the 2021 recovery rebate credit phaseout ranges, implementing these sound planning strategies now can meaningfully increase the ultimate amount of 2021 recovery rebate credit they receive.

Jeffrey Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, MSA, a Financial Planning contributing writer, is the lead financial planning nerd at