Social Security operates as an instrument of income replacement. As such, its benefits are much higher for those who log a lengthy career and proportionally limited for those who don’t work for long.

For someone who intends to retire early, however, the Social Security Administration’s projected benefits calculation may turn out to be substantially higher than what that person will actually receive.

The ultimate number may not stop a prospective early retiree from leaving the workforce, but as advisors, we are obliged to examine the individual’s inflation-adjusted historical earnings to understand whether or how much of an impact their decision may actually have on projected benefits — and give appropriate advice.

INCOME REPLACEMENT RATE

Although not commonly understood, the calculation of Social Security benefits is really nothing more than an income replacement formula. Just as a pension might offer a replacement rate of up to 70% based on the average of your last five years of wages, Social Security also provides benefits that replace your earnings based on years of service.

The primary difference is that Social Security uses a 35-year average of earnings that accrues based on your years of work rather than just your last three or last five years of wages. Furthermore, the replacement rate itself is based on your income, with those at the lower end of the income spectrum getting a higher replacement rate.

The individual’s 35-year average of earnings is known as

The final benefit is known as the PIA (Primary Insurance Amount) and becomes available to the retiree at

The following scenarios illustrate the various impacts of career duration and earnings on estimated Social Security benefit.

Example 1. Over his lifetime, Charlie’s 35-year average income was $73,000 once adjusted for inflation, or $6,083/month. As a result, Charlie’s Social Security benefit would be 90% of the first $885/month, equal to $796.50/month in benefits, plus another 32% of the next $4,651/month of income, equal to $1,488.32/month in benefits, plus 15% of the last $547.33/month in income, equal to another $82.10/month in benefits. This means his total benefit is $796.50 + $1,488.32 + $82.10 = $2,366.92/month at full retirement age. Relative to his $6,083/month of AIME, this is an effective replacement rate of 38.9% of his income in retirement.

To the extent the individual starts taking benefits early (i.e., before full retirement age of 66), the PIA

Example 1b. Continuing the prior example, if Charlie was born in 1955, such that he’s turning 62 in 2017, his full retirement age would actually be 66 years and two months, which means starting his benefits as early as possible would bring a reduction of 6.66%/year x 3 years + 5%/year x 1 year and 2 months early = 25.83% reduced. Thus, his $2,366.92/month benefit at full retirement age would be only $1,755.47 by starting as early as age 62.

BENEFIT PROJECTIONS

As noted earlier, Social Security benefits are calculated as an income replacement rate based on 35 years of your highest historical earnings, adjusted for inflation. This means that when you’re just getting started as a teenager or 20-something, most of your 35-year average of earnings would be $0, and any projection of Social Security benefits based on actual earnings would be near $0. You wouldn’t really know whether your Social Security benefits were on track to replace your income in retirement until you actually had 35 working years to see the cumulative benefit — even if you knew and were planning to be working that long up front.

Accordingly, the Social Security Administration provides a regular statement to project future Social Security benefits, assuming that you will continue to earn at your current income level, based on your earnings for the past two years. This is reflected as your

Example 2. Andrew is a 32-year-old whose income has averaged about $35,000/year over the past 12 years, including both work he did enrolled and after college). For the past two years, his annual salary is up to $48,000/year.

Accordingly, when his $35,000/year of average earnings for 12 years is stretched across the 35-year formula, Andrew’s lifetime inflation-adjusted average earnings are only $12,000, including 23 years of $0s, or just $1,000/month. This means his benefits would only be 90% x $885/month (the first replacement tier) + 32% x $115/month (his earnings in the second tier) = $796.50 + $36.80 = $833.30/month.

However, if Andrew really does plan to work for the rest of his available working years until full retirement age (67 for a 32-year-old today), he can add another 35 years of income from here at his current $48,000/year salary, which would overwrite all of his prior years of earnings with higher income years, and provide him with a future Social Security benefit based on $48,000/year (or $4,000/month) of earnings. This would result in a Social Security benefit of 90% x $885/month + 32% x $3,115/month = $796.50 + $996.80 = $1,793.30/month.

As a result, Andrew’s Social Security statement will show a projected benefit of $1,793.30/month, and not $833.30/month, even though the $833.30/month is the only benefit he’s actually earned to this point. That’s because $1,793.30/month is what he’s on track to earn based on his employment and earnings trajectory, assuming he continues to work at his current pace.

Notably, the future benefit a prospective retiree would actually receive at full retirement age will be even higher than the projected benefit amount reported on the Social Security statement, due to the additional impact of inflation between now and full retirement age. Future benefits are projected assuming future earnings, but are reported in today’s dollars, and as a result do accurately project the purchasing power of future benefits, even though the actual future dollar amount will be higher as inflation continues to compound.

Current-dollar value of Social Security benefits may even be understated, as Social Security actually adjusts the benefits into today’s dollars using

EARLY RETIREMENT’S IMPACT

It’s crucial to recognize that the standard Social Security statement projects benefits assuming continued work, as it means that not working as late as full retirement age can reduce prospective benefits. That’s not because future benefits are actually reduced by stopping work early — though they are reduced by starting benefits early — but simply because projected statements assume continued work by default, such that its absence will still result in a lower actual benefit in the future than what was previously projected.

However, the actual impact on Social Security benefits of stopping work before full retirement age varies heavily, depending on what the prospective retiree had already earned in benefits — or more specifically, what additional years of work and income would have done to that individual’s highest-35-years earnings history.

After all, if the worker already has 35 years of work history, all of which are at least as high as current earnings after adjusting for inflation, then the prospective retiree isn’t actually earning any further increase in benefits by continuing to work. That’s because the AIME formula only counts the highest 35 years and drops the rest. Consequently, if the prospective retiree isn’t adding new years that are higher than the existing ones, the additional years of work have no impact — which means stopping work early has no adverse impact, either.

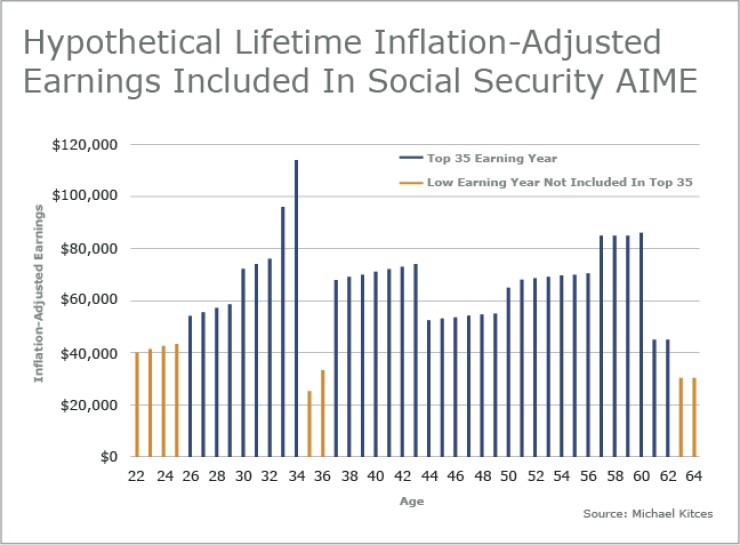

For instance, the chart below shows an individual’s historical, inflation-adjusted earnings over a career, including a substantial ramp-up in the early years, followed by a career transition with low income, then a steady series of raises, with a few wind-down years of consulting work at the end. The top 35 years are shown in blue, and the low years — not included in the top 35 — are shown in orange.

As the chart above shows, additional years of work at the current consulting levels will have no impact on benefits because there are already 35 years of historical earnings at even higher levels. As a result, quitting work after age 64 won’t have any impact on the benefits that were originally projected to begin at full retirement age of 66. Though notably, starting benefits as early as age 64 would still reduce them by 13.3% for claiming early.

On the other hand, if the prospective retiree has more than 35 years of historical earnings, but not all of those prior years were as high as today, there may still be some prospective impact to retiring early. In this case, it’s because the additional years of work are replacing prior years in the calculation of the highest 35 years of benefits. This means that eliminating them from the projection by retiring early sacrifices some opportunity for increasing benefits.

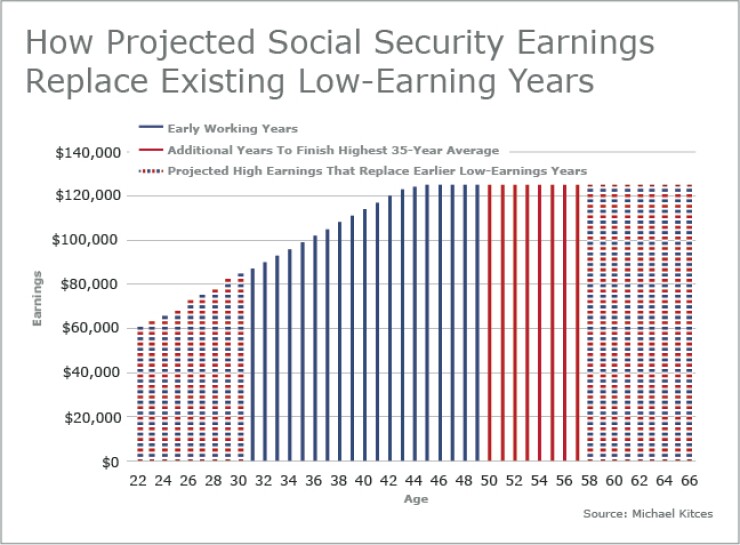

For instance, the chart below shows the historical, inflation-adjusted earnings of an individual who has been in his peak earnings years since a big promotion in his mid-50s, and is trying to decide whether to retire early at age 60. His current Social Security statement projects his retirement benefits to be $2,374.24, which implicitly assumes he will keep earning his $110,000/year salary until full retirement age, which means he’d have to log six more years to knock out his $40,000/year earnings from back in his 20s.

Given that he’s at the 15% replacement rate level as a result of how high his AIME already is, each additional year he works increases his benefit by $166.67 x 15% = $25/month, or $150/month for six more years of working. Given that his projected retirement benefits were already $2,374.24, this means his benefits will be reduced by 6% by retiring at age 60 — even if he waits until full retirement age to receive the full benefit.

For those who don’t even have 35 years of historical income though, the effect of retiring early can be even more substantial. For instance, if the individual above had been aiming to retire earlier, then that individual might not have 35 years of earnings history to draw from. The additional projected years of working through full retirement age would have both filled out the remainder of the highest 35 years, and replaced lower earning years with new, higher years. The exclusion of both — if retirement occurs early — can be massive.

As the chart above shows, projected Social Security benefits would include eight more years of $125,000/year earnings to complete the 35-year earnings history, and the subsequent eight years would further increase AIME by overriding eight early years that were at lower income levels.

As a result, projected Social Security benefits would be $2,854.42/month based on an AIME of $9,885.71/month ($118,628.57/year). However, if the individual actually retires at age 50, and simply locks in the benefits he’s actually earned, the 35-year AIME — with only 28 years of actual earnings history to draw from — would be only $8,220.24, and Social Security retirement benefits would be just $2,606.21/month, not $2,854.42 as projected with continued work.

PLANNING FOR IMPACT

It’s important to remember — beyond the impact of retiring early on the calculation of projected benefits — that taking Social Security early can reduce benefits by more than 25% due to the reduction on Social Security benefits claimed

However, many prospective retirees can ameliorate this impact simply by retiring early and waiting to begin taking Social Security benefits by spending down other assets in early retirement instead. This is often a good deal, given both the potential impact of the

Yet as shown here, early retirement has a second effect: It reduces the calculated Social Security benefit too, or at least fails to accrue more benefits, by continuing to work relative to the projected benefits on the Social Security statement. That’s true even if the retiree waits until full retirement age to actually begin taking benefits.

However, the actual magnitude of the reduction will depend heavily on what the early retiree’s recent — and therefore projected — income is, relative to that individual’s earnings history, in order to understand whether more years of work replace prior years in the high-35 formula, or not. Log into or create an account at the SSA’s

Unfortunately though, since Social Security benefits are calculated based on the highest 35 years of inflation-adjusted earnings, it’s also necessary to adjust prior income into the current year’s dollar amounts. Based on the

From there you can then assess whether or how much additional income years between now and retirement may be impacting projected Social Security benefits, and to what extent the additional income years may either be increasing AIME by adding more years to the 35-year average, increasing AIME by replacing prior lower income years with new higher income years, or not impacting AIME at all because the highest 35 years are already set from prior earnings.

It’s also important to determine whether the average historical earnings would put the individual into the 90%, 32% or 15% replacement rate tier, as the lower the AIME, the higher the replacement rate, and the greater the impact that additional earnings years will have — or conversely, the greater the adverse impact of not generating those earnings due to early retirement.

As noted in the chart above, those who don’t even have 35 years of historical earnings will be most adversely impacted by retiring early, especially if their AIME is in the 90% or 32% replacement tiers. The impact is more muted for those already in the limited 15% replacement tier, with historical annual inflation-adjusted earnings averaging in excess of $61,884/year.

Those who have at least 35 years of earnings, but who allow new earnings to replace prior year earnings, will have at least some benefit for continuing to work — and conversely, face some reduction for retiring early. The higher the income replacement rate, the more adverse the effect of early retirement. In practice though, the magnitude of the impact will depend on how much higher future earnings are anticipated to be over prior historical years. If the new years will only be $10,000/year higher in earnings than the inflation-adjusted past, the impact is still limited. If new years of income have a bigger gap, the consequences of retiring early are more severe.

On the other hand, for those where new earnings would be less than any of the prior highest 35 years of earnings history, retiring early will have no actual adverse impact on Social Security benefits. This is why it is so crucial to determine historical, inflation-adjusted earnings to make the assessment. Indeed, it’s the only way to find out if new earnings are actually higher than any of the highest in the prior 35 years.

It’s also important to remember that the earlier the retirement, the more dramatic the cumulative impact can be. While retiring one year early impacts Social Security benefits rarely by more than 0.5% to 1% of benefits — especially for those already in the 15% or 32% replacement rate tiers — retiring five or more years early can have a more substantial impact, and extreme early retirement (e.g., for those who retire in their 40s or earlier) can have a very dramatic impact, with actual Social Security retirement benefits far below projections.

With the availability of spousal and survivor benefits, however, as long as one spouse — typically the higher earner — delays until age 70 and works to maximize their benefits, there is often

For those who want a more detailed estimate of the consequences of early retirement, the Social Security Administration itself does provide access to your earnings history via the

At minimum though, it’s important to recognize that while retiring early doesn’t technically reduce benefits — as Social Security benefits accrue to the positive simply by continuing to work, as long as the working years increase your highest-35-year average — the fact that the Social Security benefit statement by default assumes that you will continue to work until full retirement age means that a decision to retire early can and often will result in lower-than-originally-projected benefits.

And the fewer years of earnings history you have, and the lower your overall income — such that you’re in the 90% or 32% replacement tiers — the more dramatic the impact.

For those with a substantial history of earnings (e.g., 25+ years), fortunately the impact usually isn’t too severe, but can still be 0.5% to 1% of a reduction for each year of early retirement, in addition to the further reduction for actually claiming benefits early, which adds up quickly for those who retire very early.

Yet the fact that it’s possible to continue to increase benefits after retirement, even and including if you’re already receiving benefits, also means that those

So what do you think? Do retirees understand the implications of retiring early on Social Security benefits? How do you help clients evaluate the decision to retire early? Please share your thoughts in the comments below.