In the early days, having expertise as an advisor meant being well-versed in what your company offered to clients. That is, becoming an advisor was as simple as mastering the inner workings of a few products.

Despite advice having grown increasingly comprehensive and holistic over the past 20 years, the

This reality has produced a voluntary desire to improve planning expertise, most directly evident in the rapid growth of CFP certification, with

This expertise shortfall is noted in my research group’s recent report,

Experience, however, is no panacea for inefficiency. As clients’ needs shift, even veteran advisors can feel they’re not performing at their highest or most time-efficient level. For support they may look to technology, yet our research suggests that the key to improving efficiency is not necessarily investing in technology to automate processes, but instead investing in the human capital of advisors themselves.

That way, with deeper and more focused expertise — plus a wider range of skills to which various planning tasks can be appropriately and cost-effectively matched — advisors can rest assured that they’re providing value that can’t be productized or automated away.

EXPERIENCE-EXPERTISE GAP

One of the fundamental challenges in creating a comprehensive plan is the time it takes to gather the requisite data to analyze a client’s full situation; figure out how to craft appropriate recommendations; present and communicate those recommendations; and implement and support the client during the ongoing monitoring phase. It shouldn’t come as a surprise, then, that we found it takes an average of nearly 15 hours to create a comprehensive plan.

For advisors providing ongoing advice, the planning process itself doesn’t end at the stage of delivering the plan. Indeed, there’s still an implementation phase and subsequent ongoing monitoring required — not to mention

From an efficiency perspective the fundamental challenge with the planning process is that so much of it is client-facing — a reality that planning software

In fact, the only phases of the

So, what can be done to improve the expediency of the client-facing portion of the planning process? The answer involves developing greater expertise through programs like CFP certification.

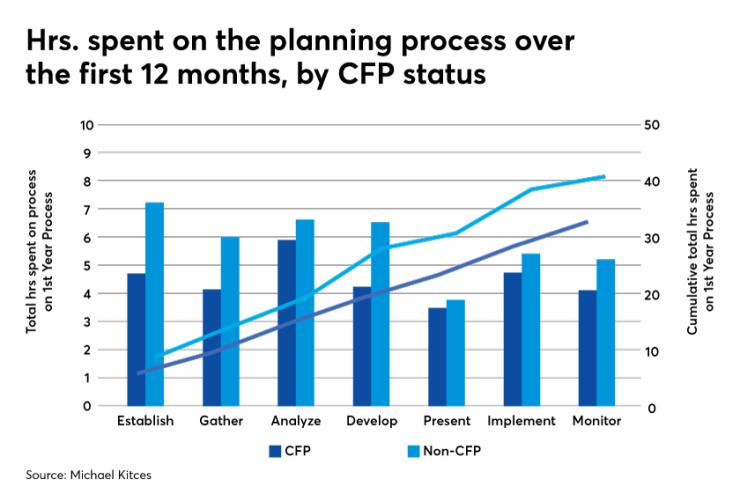

In the course of our research we found that the average time to complete the planning process for non-CFPs is a whopping 41 hours throughout the first year, while CFP certificants average just 32 hours. CFP certification effectively leads to a 22% improvement in the time efficiency to deliver planning.

And as the chart above reveals, the bulk of time savings doesn’t result from the plan creation phase, but rather the upfront relationship and data-gathering phase, together with the subsequent implementation and ongoing monitoring phases.

In other words, CFP certification appears to improve the efficiency by which planners ask the right questions up front.

Granted, any experienced planner who has executed enough plans eventually begins to refine how they ask questions, analyze client situations and deliver recommendations. But experience alone isn’t enough. It’s not about how many hours are spent learning a skill, but whether the individual engages in a process of

As for non-CFPs, those with more experience actually spend even more time per plan in the first year — increasing from an average of 41 hours per year to 52 hours, for a 27% loss in efficiency — while those with CFP certification spend less time per plan as their experience grows, with the average time dropping from 32 hours to just 29, a 9% improvement.

In other words, when it comes to the planning process an experience-expertise gap emerges if practitioners gain more experience, but don’t match it with a growing base of knowledge expertise.

NARROWING THE SCOPE

Such gaps emerge over time because planners who gain experience — and the confidence to deliver their services — often tend to progress upmarket to more affluent clients, who typically have more complex situations.

But more affluent clients also tend to be more time-consuming and more burdensome to the experienced advisor, because every client’s situation is likely both complex and substantively different. These factors result in a non-trivial amount of research time, a problem that is only amplified if the advisor lacks the expertise that CFP certification confers — unless the advisor tries developing a more repeatable expertise instead of just developing a broader and/or deeper one.

Indeed, one of the key aspects of making the planning process more efficient doesn’t just come down to developing more expertise — i.e., to be able to ask better questions, speed the development of trust and arrive at recommendations faster — but also to narrowing the

There is substantial efficiency to be gained in

Similarly, the advisor who specializes in executives from a particular corporation only needs to learn the company’s executive comp plans once. And the advisor who specializes in student loan strategies eventually masters all the rules, and can largely forego researching the next complex client situation.

An added benefit of developing repeatable expertise is that it narrows the scope of where the advisor themselves must focus for continuing education. Just as the neurosurgeon continues cultivating knowledge by seeking out the latest research, so too can the niche-based advisor dive deep on the professional development most relevant to them.

This type of specialization, including and especially within a larger firm environment, allows the firm in the aggregate to be far more efficient. For instance, it’s common for large law or accounting firms to have practice areas — domains of expertise within the firm – where a group of attorneys or accountants, respectively, meet specific client needs with specific expertise.

Developing repeatable expertise also helps keep costs down for the consumer. Even though a specialized tax expert may charge a far higher hourly rate for their time, it’s often deemed worthwhile because it’s still less time-consuming — and thus ultimately less costly — than a generalist accountant learning on the clock, and who may still not ultimately have sufficient expertise to solve the problem.

The key point is that developing repeatable expertise isn’t just about gaining more expertise with CFP certification or

LEVERAGING PARAPLANNERS

The third way the planning process can be made more efficient is by better focusing the lead advisor’s time on the most necessary and appropriate tasks, and delegating the rest to a paraplanner.

In the course of our research we found that when an experienced advisor utilizes a paraplanner for support, they wind up spending almost four hours more per week, or half a business day, on business development and client-facing activities. Assuming an average meeting time of one hour, this would amount to more than 200 additional client-facing meetings over the span of a year.

Accordingly, the average lead advisor operating as a solo without a paraplanner claimed an average of 73 ongoing clients, while the average advisor with a paraplanner for support was servicing 120 clients. That in turn resulted in the solo generating

A key distinction is that paraplanners don’t make the planning process

Recognizing that the breadth of the entire planning process spans beyond just the analyzing and development phases, advisory firms that utilize paraplanners across the entire cycle — from data gathering and implementation meetings to the ongoing client service requests in the monitoring phase — are ultimately able to service 64% more clients and generate 80% more revenue.

This in turn is more profitable for the business, because a paraplanner performs essential tasks at a lower salary than the lead advisor would command, allowing the advisor to focus their time on activities that meaningfully boost the bottom line more cost-efficiently.

The key point is to recognize that the time efficiency of a paraplanner is about more than just delegating or outsourcing the time it takes to construct the plan itself — though doing so certainly helps, and there are a

Viewed another way, the efficiency of a paraplanner is not necessarily in their ability to absorb small clients, but more in their doing a portion of the work for each client, allowing a splitting of tasks between the advisor and paraplanner — akin to how doctors rely on nurses — in the most cost-effective manner.

Planning as a business remains viable in large part because it goes beyond what technology alone can accomplish. In a world where most clients don’t even know