The allure of starting a small business employer retirement plan can seem self-evident. Not only can business owners provide employees with a tax-deferred means to save, but a 401(k) plan with profit-sharing also gives business owners a way to save more for their own retirements on a tax-preferenced basis — reducing their tax exposure in the process. In fact, it’s not uncommon to see founders saving more in taxes than it costs them in employee contributions.

As compelling as that might seem, it’s important to note that setting up a plan is merely a strategy for tax deferral, not tax savings. And the cash outlays made on behalf of employees are of course a permanent expense that owners can never recapture.

The net result is that it’s often better for business owners to skip the small business retirement plan, opting instead to simply pay their own taxes and save the net proceeds. They may lose out on the upfront tax deduction on the contribution, but by avoiding employee contributions they otherwise may not have needed to make for compensation purposes, the net value can often still be higher — especially for taxable accounts that are managed to take advantage of the available 15% long-term capital gains and qualified dividend rates.

What follows is a look at when and how these plans can be used to good effect — as long as tax deferrals aren’t mistaken for tax savings.

Starting a small business is tough. According to

For businesses that beat these daunting odds, the problem may eventually become finding ways to minimize taxes on profits. This is where small business retirement plans come in — not merely as a benefit for employees, but a way for owners to save their profits on a tax-preferenced basis.

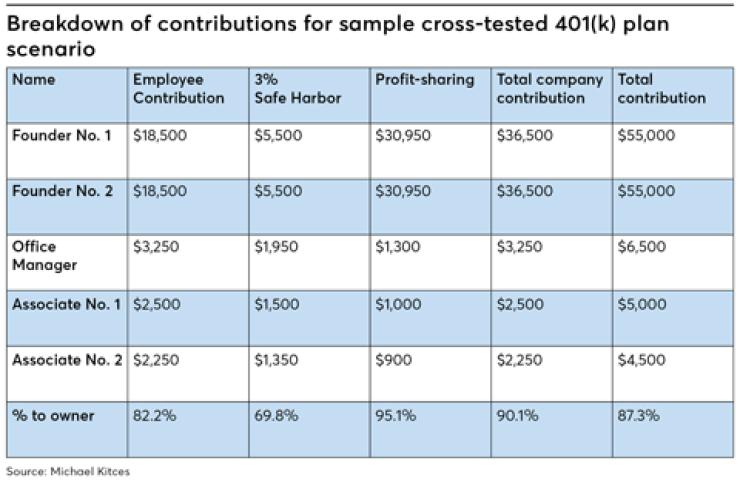

Imagine a small consulting business with two owners in their 40s who have three employees: an office manager in her late 40s and two associates, aged 32 and 28. The business now grosses about $600,000/year in revenue, pays the office manager $65,000, the associates $50,000 and $45,000, respectively, and has about $70,000 in other business expenses. This results in a net cash flow of $370,000/year for the business, which the owners split 50/50 for $185,000/year in profit income.

The income exceeds what each owner needs to live on, and as a result they become interested in generating some additional tax benefits on their savings. They decide to open a 401(k) with profit-sharing for the business, with a plan to make a 3%/year safe harbor contribution.

They reach out to a 401(k) consultant to set up the plan, and it comes back as shown below.

In essence, the 401(k) with profit-sharing assumes that the owners will max out their salary deferral component at $18,500, which leaves room for another $36,500 of profit-sharing contributions to get them to the

Because the owners are already planning on making a 3% safe harbor contribution upfront to all employees, the business must then contribute another 16.73% of payroll in profit-sharing contributions to get the owners up to the maximum limit — and then must make a similar 16.73% profit-sharing contribution to the rest of their employees.

The end result is that the business owners contribute $110,000 to themselves between salary deferral, safe harbor and additional profit-sharing contributions, which at their 32% tax rate saves them $35,200 in taxes. In turn, the company is required to contribute only $31,568 to employees to access this tax benefit.

This admittedly looks compelling, as the owners end up with $110,000 in tax-deferred accounts compounding future growth, along with $35,200 - $31,568 = $3,632 of extra cash in their pockets by setting up the plan, which is more than enough to cover the administrative cost of establishing and maintaining the plan.

A MUDDLED PICTURE

While this qualified plan scenario may seem to be a positive for the small business, it will actually reduce the business owners’ wealth in the long run because the owners have confused a tax deferral with tax savings.

The owners actually didn’t eliminate $35,200 in taxes by establishing the 401(k) plan. Rather, those taxes were merely deferred, and when that $110,000 is withdrawn, $35,200 of taxes will be due. In other words, the savings are only temporary, while the contributions made to employees are permanently logged as an expense of the business.

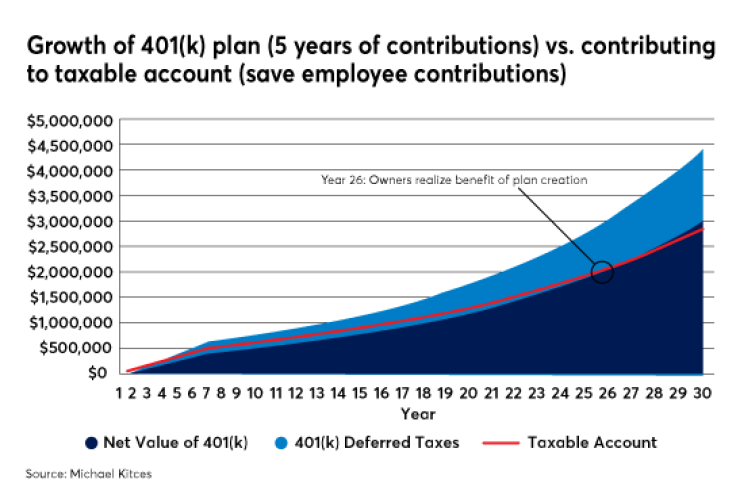

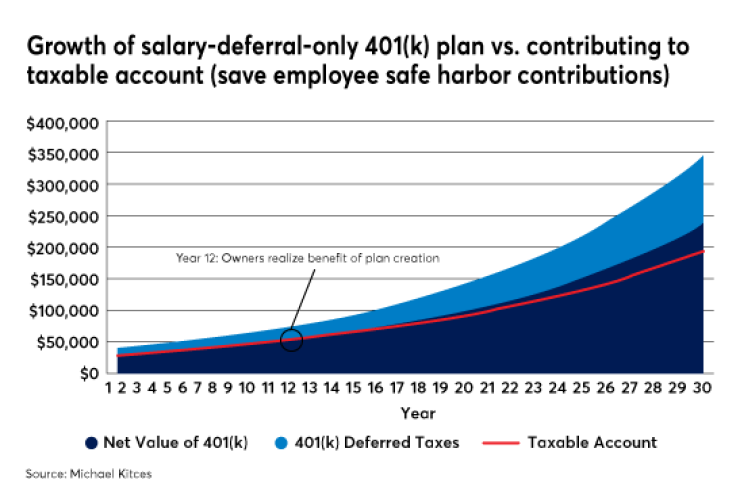

The projection below reflects the end result of this $110,000 over time, assuming an 8%/year annual growth rate on the 401(k) plan and a 32% tax rate on the proceeds. Accompanying this is an alternative scenario where the business just skips the qualified plan, takes the $110,000 of compensation directly, pays the 32% tax rate now and reinvests the $74,800 of proceeds —assumed to also earn 6.8%/year, net of 15% dividend and long-term capital gains rates.

Notably though, the preceding qualified plan strategy invested $110,000 and had to spend another $31,568 in pre-tax employee contributions to make it work. This means that if the plan weren’t established, the business owners would’ve had another $21,466 to invest as well, representing the after-tax dollar amount of the contributions that were not made to employees. Thus, had the business owners skipped the qualified plan altogether, they would’ve had $74,800 + 21,466 = $96,266 available to invest in a taxable account.

As the results clearly show, foregoing the 401(k) plan actually nets the business oners far more for decades than creating the tax-preferenced retirement account. This, despite the establishment of the plan resulting in $3,632 of net cash flow savings in the initial year. The problem again is that the deferred tax liability on the 401(k) plan eventually must come due, while the contributions made to employees are permanently gone.

It’s worth noting that over time the gap between creating and not creating the plan narrows, as there is still some value to

The projection above is also based on just a single year of contributions. If we assume the business continues making contributions for five years and then projects out the value over the long term, it’s even worse.

Repeated over time, the hole the business owners dig for themselves in exchange for temporary tax savings becomes even deeper — to the tune of more than $120,000. The cumulative impact can be felt in the 26 years it will take to recover, and by that time the business owners would likely already be retired.

CROSS-TESTING

Advisors with qualified plan design experience for small businesses may have noted that in the earlier example, a qualified plan that contributes only 69.8% of company contributions to the founders/owners is not necessarily ideal.

Unfortunately though, the owners in this example are too young — compared to a non-highly compensated office manager who is older — to make a

If the total contributions to owners were 19.73%, a cross-tested plan that separates the highly compensated owners from the non-highly compensated remaining employees would permit employees to receive the lesser of one-third of that amount (6.58%) in contributions, which would amount to 5% in contributions — or a mere 2% above the 3% safe harbor contribution already being made.

The end result would be a substantial reduction in the total amount of contributions being made to the non-highly compensated employees, for a total cost of just $8,000 instead of $31,568, while the owners would make the same $55,000 in total contributions.

A whopping 90.1% of the employer contributions would consequently go to the owners. And in the initial year, the business owners would save $27,200 in cash flow — $35,200 in taxes not paid on the $110,000, reduced by $8,000 of employee contributions.

Nonetheless, that $27,000 represents a tax deferral, not tax savings. The $35,200 of taxes not paid upfront will still have to be paid someday by the business owners, while the $8,000 in employee contributions are a permanent expenditure.

Accordingly, if the business owners repeat this strategy for the next five years and then allow the plan to compound, it still takes more than a decade for them to come out ahead, when considering the value of simply keeping their $110,000 of compensation and $8,000 of employee contributions, paying their 32% tax rate and reinvesting the $80,240 remainder.

It’s also important to note that this assumes 100% of growth/gain is turned over every year — albeit at 15% capital gains and qualified dividend rates. If the taxable account is managed at least somewhat tax efficiently — for instance, with a 2.5% dividend and just a 33% turnover — it takes even longer for the cross-tested qualified plan scenario to ever catch up, despite skewing 90.1% of company contributions to the business owners.

In other words, even in situations where upward of 90% of plan contributions go to the owners, the 401(k) plan still doesn’t come out ahead until the founders are on the cusp of retirement nearly 20 years later — presuming they invested tax efficiently along the way. Because again, the value of tax deferral just isn’t that significant compared to a reasonably tax-managed taxable portfolio.

SAFE HARBOR STRATEGIES

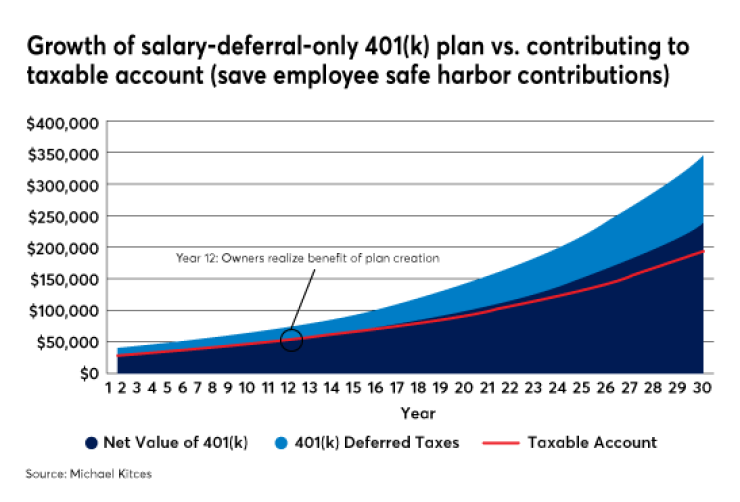

Given how unfavorably cross-tested profit-sharing contributions can play out, some business owners may be tempted to fall back on just maxing out the salary deferral component of $18,500, and making what is typically a 3% safe harbor mandatory contribution to employees.

Yet as we’ve already seen, making employee contributions so that owners can contribute and defer more is not necessarily a winning proposition — both when it comes to profit-sharing contributions and even safe harbor contributions.

Assume the owners decide to simply eschew profit-sharing contributions altogether, and just make their $18,500 salary deferral contribution, along with a 3% safe harbor contribution to all employees, including themselves.

The net result is that the two owners are able to contribute a total of $37,000 in salary deferrals, plus $11,100 in their own safe harbor contributions, for a total of $48,100 in contributions. And in exchange, they must make $4,800 in safe harbor contributions to employees — i.e., 3% of the salaries of the office manager and associates.

Yet even adding $48,100 of employer contributions in exchange for $4,800 of employee contributions — meaning 90.9% of contributions go to owners — is not necessarily enough to make it worthwhile. This is especially true given the founders could have simply contributed to their own IRAs for up to $5,500 on a pre-tax basis — such that only $37,100 would be an actual net increase in pre-tax contributions by creating the 401(k) plan over the available alternative.

And unfortunately in the long run, that’s just not enough tax deferral for a cost of $4,800 in employee contributions.

As the results reveal, even just making safe harbor contributions to a 401(k) plan to increase the founders’ retirement account contribution limits above the traditional IRA threshold may not be worthwhile after all — and could set them up to fare even worse when accounting for ongoing 401(k) administrative costs.

The key point is not to suggest that it’s bad for business owners to create 401(k) plans, but it is important to recognize that even being able to skew contributions 80% to 90%-plus toward owners may not be enough to make it financially beneficial in the long run. That’s down to the simple fact that employee contributions are permanent costs, while the cash flow savings of contributing to a 401(k) plan or making profit-sharing contributions are merely tax deferrals for the business owners.

Of course, if the business needs to make those contributions to pay a competitive total compensation to employees, or as an employee benefit to attract and retain employees, then it’s simply a cost of doing business and a benefit in and of itself — for which any/all owner contributions are an added benefit.

And at least when it comes to profit-sharing contributions beyond the safe harbor, the employer

Nonetheless, for those who just want to increase employee contributions as a means of increasing the tax-deferral benefits for owners — and would rather not rely on high turnover causing unvested employee contributions to revert back — once the long-term tax deferral and not true tax savings impact is considered, qualified plans aren’t nearly as compelling as commonly believed.

So what do you think? What percentage of contributions must go to owners for a 401(k) with a profit-sharing plan to be worthwhile? Would you consider not doing a small business retirement plan in light of the long-term cost of employee contributions compared to what are only short-term tax savings for contributions? Please share your thoughts in the comments below.