After more than a decade of small or nonexistent cost-of-living adjustments to Social Security benefits, tens of millions of Americans could get their largest COLA in 13 years in 2022.

Inflationary trends across a range of industries, ones reflected in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers, have prompted The Senior Citizens League to predict a COLA of 4.7% for more than 60 million beneficiaries next year. The advocacy group released its forecast May 12, ahead of the Social Security Administration’s official COLA announcement in October.

The COLA projection has jumped by more than 3 percentage points since January, primarily due to higher gasoline costs and home heating expenses, according to Mary Johnson, policy analyst for the nonpartisan senior group. She cautions however, that the prediction on the closely watched metric, which is based on the often-criticized price index, could change in coming months due to inflation volatility.

Johnson’s estimate follows a COLA forecast in March of 3% by the

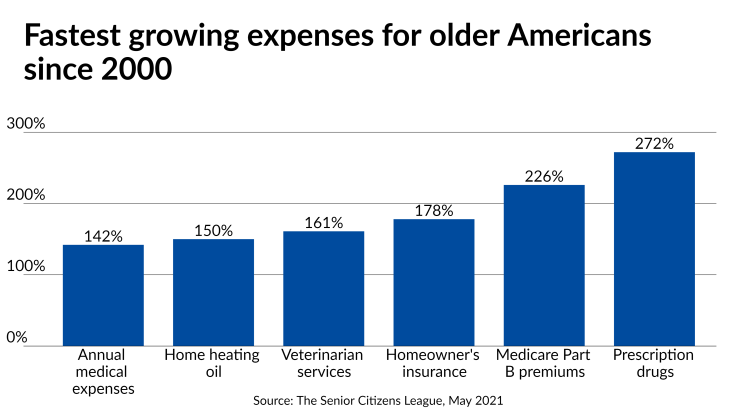

From 2000 to the present, COLAs have pushed up average monthly Social Security payments by 55% to $1,262.40, but typical expenses for older adults have grown 102% as of March, the seniors group says. In addition to higher energy costs, the rising price of items like bread, coffee, chicken, beef and fish will force some older Americans to pick between a meal and medication, Johnson says.

“That is what has worried me because so many older people — retirees who have very modest benefits — often don't have enough to get through an entire month without having to make some choices,” she says. “What all these rising prices do is, they erode the buying power of Social Security benefits. The longer people spend in retirement, the worse this situation gets.”

Senior advocates have been calling for years for legislation that would connect COLAs to a different index called the

The alternate index that’s specifically tied to the spending of adults 62 or older has yielded inflation estimates that are about 0.2 percentage points higher than the current criteria,

The GAO warned in a previous report that the chained index would decrease retirement income by 6% in low-income households and only 1% in affluent or wealthy ones.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics, the agency tracking the consumer price indices, hasn’t evaluated whether the current formula covers “the outlets where members of this older subpopulation shop, the prices they pay or the mix of goods and services they purchase,” according to the GAO report. The accuracy “may be deteriorating” due to lower response rates and demographic shifts away from blue-collar jobs reflected in the current formula, GAO says.

“Without taking actions to understand available options for a cost-efficient solution, BLS lacks reasonable assurance that adjustments to Social Security and other retirement benefits are based on indexes that reflect what they are intended to reflect,” the report states. “Specifically, benefits could be subject to adjustment based on potentially inaccurate information.”

At least 10 countries’ national statistical agencies create indices tracking the older subpopulations and four of them — Australia, the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic and Hungary — use the specific indices for older adults to tweak their national pension benefits. None of the 36 countries studied by the GAO use the chained index to adjust their benefits. The agency called on BLS to find cost-efficient means for evaluating the accuracy of its data.

Regardless of the debate around indices and the larger one on long-term solvency, a higher COLA next year will add to concerns about inflation as the government spends heavily on coronavirus relief and the Fed holds interest rates low. Skyrocketing lumber prices have already

“I've always seen how Fed action has seemed to have a dampening effect on the COLA and it being low,” she says. “Right now they're deliberately not raising those rates and we're beginning to see some real inflation. This is the first time I've been able to watch what happens when they don't raise the interest rates.”