Upon reaching retirement, a retiree theoretically begins to spend down money and enjoy it. Yet in practice, a growing base of research finds that retirees just continue the growth of their pre-retirement portfolios, suggesting a consumption gap between what retirees could and should spend versus what they actually do.

However, given compounding inflation can double or even quadruple spending needs after 30 years, retirees actually should allow their portfolios to grow slightly for at least the first half of retirement. It’s a necessity just to cover later years’ spending needs at their inflation-adjusted levels.

Furthermore, given uncertainty about the length of retirement, inflation rates and the favorability of portfolio returns, retirees often spend even less in the early years just to defend against these risks — an approach now dubbed the safe withdrawal rate. Generally, however, markets and inflation don’t actually spiral out of control, so following a safe withdrawal rate approach only increases the likelihood that portfolios will continue to grow throughout retirement.

Consequently, while most retirees accumulate a portfolio with the plans to spend it in retirement, when faced with the ever-open-ended potential of living many more years they may feel compelled to keep extra assets available, and never actually deplete the retirement portfolio, even in their later years. This isn’t a sign of inefficient portfolio spending or a consumption gap, but merely a prudent response to an uncertain future.

NOT SPENDING ENOUGH?

The classic view of retirement is that in the early years, people save and invest — i.e., the accumulation stage — in order to retire and consume all of their savings during the decumulation stage. As the saying goes, “You can’t take it with you,” so you may as well spend it while you can. The whole point of retirement is to enjoy the fruits of your labor, right?

The classic view of retirement is that in the early years, people save and invest — i.e., the accumulation stage — in order to retire and consume all of their savings during the decumulation stage.

Of course, spending down retirement assets smoothly is no simple feat. From coordinating among various sources of retirement income, to the tax consequences of portfolio withdrawals and

The caveat to this conventional view of retirement, though, is that it simply doesn’t appear to be happening. A

-

These planning strategies can prevent beneficiaries from biting off too much — or too little.

August 19 -

Knowing how and when to withdraw can save clients big in their golden years.

August 9 -

A NING trust can provide significant savings and help clients avoid gift tax ramifications.

June 6

As a result, from the beginning of 2000 to the end of 2008 — a very challenging time of mediocre returns for retirement portfolios, when in theory account balances would have dipped with ongoing withdrawals — the average financial assets of wealthy retirees still continued to increase. Thus, the researchers identified a consumption gap between what spending the portfolios could support, and the lesser amount that was actually getting spent.

The straightforward conclusion is that retirees are “doing it wrong” by not even spending the full amount of their retirement and portfolio income in retirement, instead allowing their portfolios to grow. But the question arises whether retirees are truly under-spending in retirement, or are they actually following a rational retirement spending strategy for a long time horizon with a lot of big uncertainties?

WHEN SHOULD RETIREES SPEND?

While the conventional view is that once you hit retirement, it’s time to start spending down, the process isn’t so straightforward.

Timing the liquidation of retirement assets is especially complicated by the role of inflation. Over a multi-decade time horizon, even modest inflation can add up significantly. What starts out as $40,000/year spending can wind up anywhere between $70,000/year and $164,000/year after 30 years, just to maintain the same standard of living, depending on whether annual inflation averages just 2% or averages as high as 5%.

Presuming a 5% annual inflation rate, inflation-adjusted spending needs could quadruple by the end of retirement.

Presuming a 5% annual inflation rate, inflation-adjusted spending needs could quadruple by the end of retirement. Accordingly, to sustain a multi-decade retirement with rising spending needs, it’s necessary to spend less than the growth/income in the early years, just to build enough of a cushion to handle the necessary higher withdrawals later!

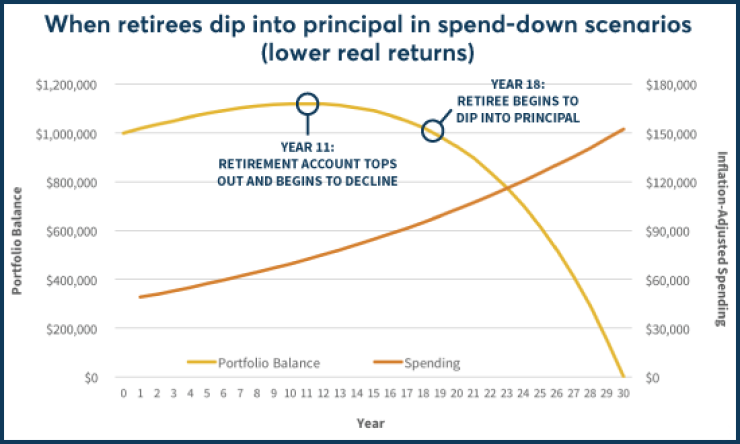

Imagine a retiree with a $1 million balanced portfolio, and wants to plan for a 30-year retirement, where inflation averages 3% and the balanced portfolio averages 8% in the long run. To make the money last for the entire time horizon, the retiree would start by spending $61,000 initially (a little over 6% of the starting account balance), and then adjust each subsequent year for inflation, spending down the retirement account balance by the end of the 30th year.

As the chart reveals, though, a retiree who plans to spend down assets by the end of a 30-year retirement would still spend less than the growth for the first 10 years, and wouldn’t actually dip into principal until the 18th year.

And that’s assuming modest 3% inflation and long-term returns of 8% (the approximate averages for the past 100 years). If instead the retiree had a gloomier outlook, and projected a balanced portfolio to grow at only 7% while inflation could be as high as 4%, spending would be only $49,000 initially, the portfolio would peak in year 12, and dipping into principal wouldn’t occur until the final decade of retirement.

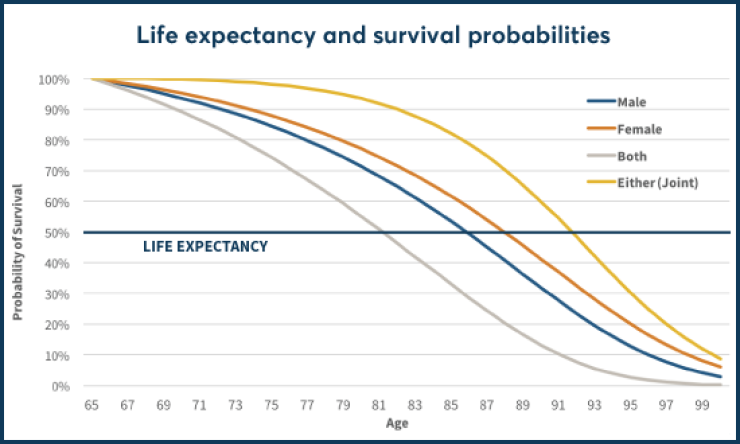

In the context of this more conservative scenario, it’s notable that a 65-year-old retiree’s

It’s also notable that since most spend-down strategies won’t actually begin spending principal until the final decade of retirement, required minimum distributions won’t likely deplete the retirement portfolio either. To the extent they’re not needed, the RMDs may just be forced transfers of investments that were growing in the IRA and will now grow in a taxable investment account instead — but still not yet be spent.

MANAGING RISK

Aside from the challenge of spending down principal, an additional concern is that returns and inflation are not as certain as even straight-line conservative projections suggest. Instead, as we know from the research on

As the saying goes, “You can’t take it with you,” so you may as well spend it while you can. The whole point of retirement is to enjoy the fruits of your labor, right?

The solution is to spend less, at least initially, just in case an unfavorable sequence occurs, which is the origin of the so-called

Of course, the caveat is that on average, the 4% rule is unnecessary. As noted earlier, given long-term average returns, the sustainable withdrawal rate would be over 6%. The 4% rule is built for environments that have horrible returns in the first part of retirement.

If the retiree starts with a 4% initial withdrawal rate and actually does get anything close to merely average returns, and not an especially bad early sequence, the portfolio will just compound even more growth in the early years and get even further ahead.

Accordingly, the chart below shows the path of wealth that would have occurred in any particular 30-year historical scenario going back to the 1870s, assuming a 4% initial withdrawal rate and with the dollar amount of spending adjusted each subsequent year for actual inflation. The chart further presumes investing in an annually rebalancing 60/40 portfolio, with the actual stock and bond market returns that occurred year by year.

As the results show, the decision to follow a 4% initial withdrawal rate makes it

CAN RETIREEES SPEND DOWN?

The bottom line is that a normal retirement spending pattern suggests that a total spend-down wouldn’t typically happen until retirees were well into their 80s at best.

The bottom line is that a normal retirement spending pattern suggests that a total spend-down wouldn’t typically happen until retirees were well into their 80s at best, and following the 4% rule to defend against the risk of running out of money just further amplifies the likelihood of never spending down the portfolio at all. Even a rule that

More conservatism in the early years correlates to an even higher likelihood of having ever-larger retirement account balances later. Which means figuring out how best to balance the need for prudent spending in the early years with the potential for accumulating excess retirement dollars in the later years is arguably the greatest opportunity today in retirement income planning.

Unfortunately, lifetime immediate annuities don’t necessarily accomplish the goal right now, given today’s environment where a lifetime inflation-adjusted immediate annuity for a married couple only pays out about 3.5% —

But at minimum, it’s crucial to recognize that accumulating excess retirement dollars and seeing the retirement account balance grow, particularly in the first half of retirement, doesn’t mean the retiree is underspending. Rather, spending down the retirement principal early in retirement would be a sign of trouble. Continued growth throughout the early years is actually the normal, prudent course for anyone who recognizes the need for the portfolio to grow in the early years, such that it defends against the uncertainties of a long retirement future.