Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

It should be simple, but it's not.

When retirement account owners move funds from one account to another, navigating the complex distribution and tax rules can quickly stimie clients and advisors alike. Yet knowing how to navigate these potentially fraught transfers gives advisors an opportunity to add value to the client relationship.

Careful maneuvers can also save clients a lot of money in the long run.

Broadly speaking, there are two ways to complete a rollover. One is indirectly — by distributing out of one account to the owner who takes possession of the cash for some limited period of time, and who then re-deposits it to a new account. The other is directly, where funds move or are treated as moved from one retirement account provider to another.

The distinction is important because when moving funds indirectly from one account to another — or in more limited situations, out of and then back into the same account — an individual must follow rules to satisfy an indirect rollover. Meanwhile, to move funds directly without triggering adverse tax consequences, either a transfer or a direct rollover can be used, depending on the situation.

Indirect rollovers describe distributions that often take the form of a check made payable to the retirement owner themselves as an individual — as opposed to another retirement account for the same owner’s benefit. That said, funds can also be directly deposited into a non-retirement account designated by the owner — e.g., a brokerage, savings or checking account, which in turn may be owned individually, jointly or via a revocable living trust.

In either case, once the distributed funds have been received by the retirement account owner — either actually received because the funds are now in the requested account, or

The 60-day clock begins to tick when an individual receives their distribution, with Day No. 1 of the 60-day window being the following calendar day. To complete the rollover in a timely manner, the funds must be in the receiving account by the end of Day No. 60. This re-deposit completes the indirect rollover process, preserving tax-deferred status.

Notably, while 60 days may seem like a significant window, many taxpayers miss the deadline and subsequently find themselves faced with an unwanted tax bill. Taxpayers under the age of 59 ½ would also potentially be subject to an early withdrawal penalty of 10%.

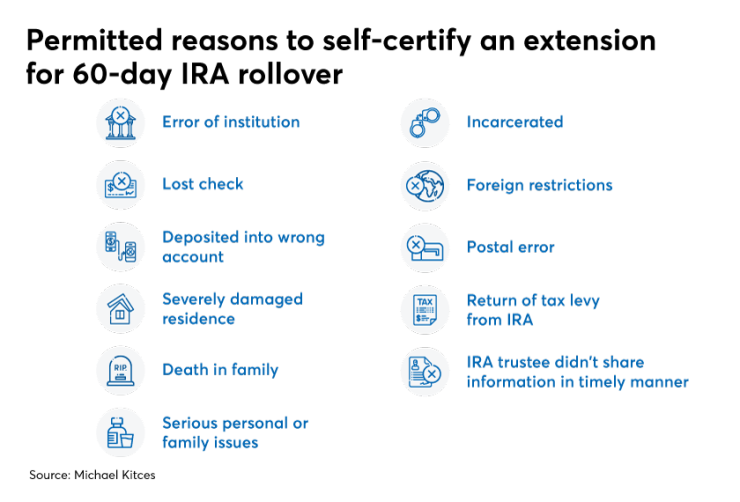

For years, the IRS was inundated with private letter rulings, or PLRs, requesting an extension of the 60-day rollover window, some of which were granted and others not. All, however, came at the expense of both the taxpayer’s time and money.

Since 2016, the frequency of such requests has dropped thanks to the self-certified corrective procedures outlined by the IRS in

Even then, the IRS can overrule the self-corrected late rollover on examination if the agency does not believe the taxpayer met the requirements outlined in the notice. Thus, even if the indirect rollover was made for one of the permitted reasons to self-certify an extension, it still behooves the taxpayer to complete the process within the 60-day rollover window to ensure the preservation of retirement assets.

MANDATORY WITHHOLDINGS

Depending on the source of an indirect rollover, other restrictions and rules can apply as well.

For instance, when distributions eligible for rollover are made from 401(k), 403(b) and similar employer plans, they are generally subject to mandatory withholding of 20% for federal income taxes. As a result, individuals wishing to move the entire account balance through an indirect rollover must generally have other assets available to make up for any amounts that need to be withheld.

Example No. 1: Andrew is a 50-year-old participant in a former employer’s 401(k) plan. Recently, Andrew decided to roll his $200,000 401(k) balance to an IRA, and without fully understanding the impact of his decision, he requested a complete distribution of his 401(k) via check, made payable to him.

When Andrew’s check arrives in the mail it will not be for the $200,000 balance in his 401(k), but rather for $200,000 - $40,000 (e.g., 20% of the balance being withheld) = $160,000. The plan will also send $200,000 x 20% = $40,000 to the IRS as withholdings for federal income taxes.

If Andrew wants to avoid a tax bill, he will have to come up with $40,000 from another source — on top of the $160,000 he receives from the plan — to get $200,000 of cumulative retirement money back into an eligible retirement plan within the 60-day rollover window.

ROLLOVER RULES

The 20% mandatory withholding rule noted above does not apply to distributions from IRAs, including IRA-based employer plans such as SIMPLE IRAs and SEP IRAs. However, such IRA account distributions are subject to a separate restriction.

To the extent someone still tries to make another indirect rollover during the one-year period, it is considered an excess contribution to the new account, and is subject to an annual 6% penalty.

AVOIDING COMPLICATIONS

If all these complexities sound unappealing — and they are —the better option is to move retirement money directly between accounts. Such direct movements can be accomplished either by a direct rollover or by transfer.

One feature shared by both direct rollovers and transfers is that neither is subject to the 60-day rollover window. That’s because when they’re made, the retirement account owner never has control over the funds.

In many instances, such movements are accomplished by the distributing custodian sending funds directly to the new custodian. Alternatively, a direct rollover or transfer can be completed by having the distributing custodian issue a check to the owner, but made payable to the new retirement account for benefit of the owner. As

Providing the distributee with a check and instructing the distributee to deliver the check to the eligible retirement plan is a reasonable means of direct payment, provided that the check is made payable as follows: [Name of the trustee] as trustee of [name of the eligible retirement plan].

So, even if a check is given to a retirement account owner, as long as the check is made payable to the new retirement account — and not the owner — the transaction is considered a direct movement. Therefore the owner is not subject to the restrictions governing indirect rollovers.

In addition to removing the 60-day time limit, moving money directly from one retirement account to another also eliminates other inconveniences.

Both direct rollovers and transfers allow a retirement account owner to avoid mandatory federal tax withholdings. As such, there is no need to make up for the missing amount with other funds.

There are also no limits on the number of times an individual can complete a direct rollover or transfer each year. Thus, while it might drive a custodian — or an advisor — up the wall, an individual can move their retirement funds directly from one custodian to another today, only to move the same funds directly to another custodian next week.

These various benefits make direct movements the preferable option in all but the rarest of circumstances. As such, individuals should be encouraged to use them — even when there’s an added cost when compared to moving funds. For instance, some custodians will process distributions requested by the account owner for free, but will charge a fee for processing direct rollover and transfer requests received from another institution.

WHAT'S THE DIFFERENCE?

Clearly, direct rollovers and transfers have a lot in common, but as noted above, they are not the same. And while the differences may at times seem subtle, failure to appreciate those differences can result in penalties or other problems.

Among those differences is the fact that a transfer can only take place between two like retirement accounts. This is generally a movement of funds between two traditional IRA accounts — including SEP and SIMPLE IRA accounts that have satisfied the two-year

Meanwhile, direct movements of money that are not between like plans are considered direct rollovers. Any time money is moved from a 401(k) or similar employer plan to an IRA, it’s a direct rollover, not a transfer.

Another significant difference between transfers and direct rollovers is that only the latter is reportable. For instance, when an IRA is transferred from one institution to another, the sending firm does not issue an

In simpler terms, when a transfer is made between institutions, the IRS should be none the wiser. By contrast, all rollovers are reportable events.

If an indirect rollover is made, the distributing firm will issue an IRS Form 1099-R assuming no such rollover is made, because the distributing firm doesn’t know whether that distribution will actually be rolled over in a timely manner or not. Thus, the distribution code reported in Box No. 7 of the form is likely to indicate Code 1 (Early distribution, no known exception), Code 2 (Early distribution, known exception) or Code 7 (Normal distribution).

And while the receiving custodian will file IRS Form 5498 to report the rollover contribution, it’s up to the taxpayer to properly report the distribution as rolled over on their income tax return to negate the tax bill that would otherwise be created.

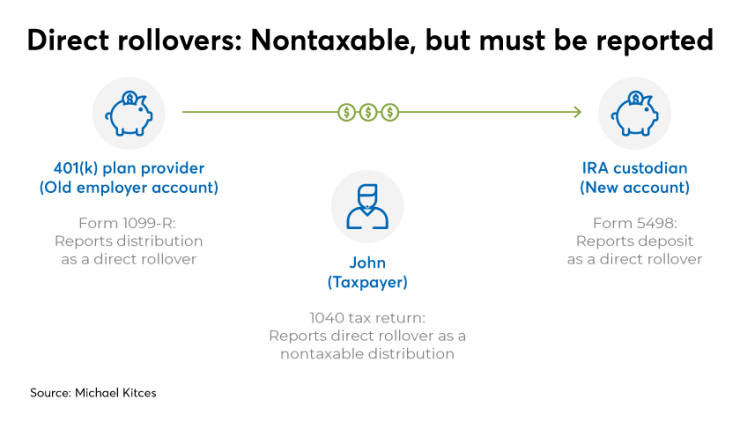

Direct rollovers are, by their very nature, nontaxable events. Despite this character, however, they must be reported by both the sending and receiving institutions, as well as the taxpayer on their personal income tax return. Thus, in these instances Form 1099-R must still be filed, but the Distribution Code in Box No. 7 of the form will generally be completed with either Code G (Direct rollover of a distribution to a qualified plan, a section 403(b) plan, a governmental section 457(b) plan, or an IRA) or Code H (Direct rollover of a designated Roth account distribution to a Roth IRA), to signify that it is not a taxable event.

Example No. 2: John has decided to move an old 401(k) to an IRA via a direct rollover. The 401(k) provider will report the distribution to the IRS using Form 1099-R and will use Code G in Box No. 7 of the form. Meanwhile, Box 2a indicates that the taxable amount of the distribution is $0.

Additionally, John’s IRA custodian will issue a Form 5498, reporting the amount deposited into the account to the IRS as a rollover contribution.

Finally, in what is often a perplexing aspect of the transaction, John will receive a copy of the 1099-R early in the year following the year of his rollover. Even though the distribution is nontaxable, the 1099-R information must be included in his tax return for the year. That is, John must still report the gross amount of the distribution on his personal tax return, even as he subsequently reports that none of that distribution was taxable.

Advisors assisting clients with nontaxable direct rollovers should coach them on the reporting to avoid surprises. That way, clients are not concerned when taking receipt of the 1099-R — bearing in mind that it may take more than a year from the time the transaction takes place for the taxpayer to receive the 1099-R.

As such, a the start of a new year, advisors should consider sending a reminder email or other message to clients who engaged in such transactions in the previous year — unless they look forward to panicked calls.

RMD CONSIDERATIONS

Another key difference between direct rollovers and transfers is that various parts of the Internal Revenue Code include restrictions on what can be rolled over from one account to another.

Perhaps the most notable prohibition can be found in

In short, required minimum distributions cannot be rolled over.

Failure to adhere to the restrictions can lead to perpetual penalties. Specifically, any amounts that cannot be rolled over but are nevertheless deposited into a retirement account are considered an excess contribution. Such amounts are subject to a 6% penalty every year the excess amount remains in the account, potentially tolling and compounding indefinitely.

Example No. 3: Allison, 75, has funds in an old employer’s 401(k) plan. After seeing an ad for low-cost investment management at a large institution, Allison decides to move her 401(k) balance to an IRA maintained by that company. However, while Alison has read enough to know to do a direct rollover, she is unaware of the prohibition on 401(k) RMD rollovers.

If left unaddressed, the amount of Alison’s 401(k) RMD would constitute an excess contribution to her traditional IRA, and would therefore be subject to a 6% penalty each year it remained in the IRA.

INHERITED IRAS

While RMDs are probably the single biggest source of transfer vs. rollover anxiety, it’s not the only one.

Note that generally, the Internal Revenue Code prohibits the rolling over of funds distributed from any inherited retirement account. However, Section 829 of the

Ultimately, the key takeaway here is that directly moving qualified retirement funds does not guarantee seamless, penalty-free movement. To avoid tax reporting obligations — to say nothing of those panicked calls — it’s essential that advisors and planners keep the aforementioned distinctions in mind. Adding value to the client relationship is the direct, and indirect, benefit.

Jeff Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, MSA, a Financial Planning contributing writer, is the Lead Financial Planning Nerd at