While the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule has generated no shortage of discussion centered around advisors and their clients, an under-acknowledged secondary shift merits attention too. Although portions of the regulation

If an advisor can make the case for active management, there’s nothing wrong with using actively managed funds. And as broker-dealers shift to being compensated by levelized commissions outside of the funds — even if the consumer still pays a 1% fee via the broker-dealer equivalent to the 1% trail in a C share — the mutual fund itself will no longer have to count the broker’s compensation against his/her own performance.

This very important secondary effect of the rule will emerge slowly over the next couple of years; it won’t light the world on fire at once. But the improving performance of actively managed mutual funds will be no less real.

THE CASE FOR COLLAPSE

Most predictions suggest the Labor Department’s fiduciary rule, thanks to its focus on low cost, will lead to the decline of actively managed mutual funds and an increase in passive ETFs. But there’s really no requirement in the fiduciary rule that advisors have to assume actively managed funds and switch to lower-cost passive funds.

The only real requirement is that if an advisor is going to use an actively managed fund, there needs to be reason and justification for paying the active manager’s fee. And if you can make the case for the active manager (i.e. they have reasonable performance), there’s nothing wrong with using an actively managed fund.

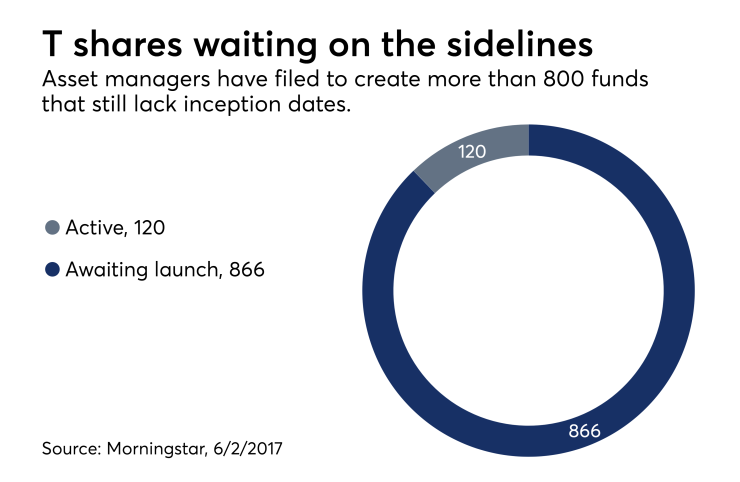

Secondarily though, the fiduciary rule dictates that if there are multiple share classes of the exact same fund, you had better use the lowest-cost version available to you. And to further ensure that advisors aren’t even tempted toward a small subset of higher-cost funds that might pay them better, institutions

This means that while there may be cost differences between passive and active funds, the advisor or broker must receive the same compensation for all of them — regardless of which one is used. And this requirement is indirectly why I recently predicted that we’re going to see a

The primary reason there are so many mutual fund share classes, with some companies having more than a dozen different ones, is basically because these companies have a dozen different arrangements to pay brokers to sell their products. And when compensation must be uniform, the mutual fund share classes become uniform as well — hence why we’re seeing the launch of T shares and clean shares.

The former will have a uniform commission paying 2.5% up front and 25 basis point trails every year thereafter no matter what fund company it is. Clean shares, meanwhile, are what they claim to be: completely clean, i.e., no commissions and no 12B-1 fees.

Yet even with clean shares, the broker still has to get paid, but that will happen by simply wrapping a levelized commission — 1% per year, for example — around the whole brokerage account by the broker-dealer themselves, resulting in broker-dealers looking more and more like RIAs that buy institutional-class shares and wrap their 1% AUM fee around it to manage it.

In fact, when the Labor Department confirmed that the fiduciary rule was going into effect on June 9, it indicated that new rules, with another streamlined exemption similar to the level fee fiduciary exemptions,

BETTER PERFORMANCE

From the perspective of actively managed mutual funds, as the entire brokerage industry shifts from A shares to lower-commission T shares — and particularly from C shares to clean shares — the cost structure of mutual funds themselves begins to change. This isn’t necessarily about the difference to the end consumer. You can pay a 1% trail on a C share or you can pay a 1% fee to a broker who uses a clean share; the consumer pays 1% either way. But the flow of payments is different.

Instead of the consumer-as-mutual-fund-shareholder paying 1% out of the fund, he/she pays 1% directly to the brokerage firm, which will then remit a portion to the broker. This is because the mutual fund itself is a clean share, which means the cost of compensating brokers will no longer be paid from mutual fund assets. Consequently, the mutual fund no longer must count broker compensation against its own performance.

What happens when every mutual fund currently paying a 1% trail to a broker suddenly no longer has to carry that 1% fee as part of the fund’s expense ratio? The expense ratio of all of those mutual funds drops by an entire 100 basis points per year indefinitely. This is a profound shift.

We all know that one of the primary blocking points that keeps actively managed mutual funds from outperforming is their cost. There are actually a number of mutual fund managers who do outperform their benchmarks on a gross basis, just not net of fees.

Granted, it’s a moot point if a mutual fund outperforms gross of fees but not net of fees, but a lot of mutual funds have not actually been underperforming by the amount of the manager’s fee. Rather, they’ve been underperforming because of the drag of the broker’s commission — that is, the original commission plus 12B-1 fees. Those aren’t investment management costs. Rather, they are marketing costs borne by shareholders thanks to the 12B-1 rules that allow expenses for marketing to be paid from mutual fund assets, and therefore count against mutual fund performance.

But again, with the shift to both lower-commission T shares and clean shares especially, the cost will still be borne by the consumer, but not out of mutual fund assets in a manner that gets held against their performance. This means that suddenly, we’ll likely see actively managed mutual fund performance starting to improve. Not necessarily because the funds are being managed any differently, but simply because their managers are no longer paying broker compensation out of their performance.

12B-1 FEE, RIP?

Back in 1980, when the rule 12B-1 was passed, the fund industry was reeling from bad performance in the ‘70s. But it determined that if it paid 12B-1 fees to the rising number of independent broker-dealers, registered reps would sell funds and bring assets into those funds. And since people weren’t as performance-sensitive back then, it wasn’t as big of a deal.

In what was probably just a coincidence, 12B-1 fees were launched on the eve of the great bull market of the ‘80s and ‘90s. Most people were consequently pretty happy with their results — and they didn’t even have good tools to analyze mutual fund performance to compare to a benchmark anyway. Subsequently, no one cared much about relative performance to benchmarks, and even if they did, they didn’t know how to measure it.

Today, however, we have the internet, and both consumers and advisors themselves have a

This creates a world in which investors are more performance-sensitive because they’re more easily able to measure investment performance against benchmarks. And were it not for the fiduciary rule, their fund managers would still allow the marketing expenses of the fund company paid to brokers to be applied against their performance records.

But now, as more mutual fund managers realize that if they switch to clean shares, they can get broker compensation out of their performance records, they’re going to push for it, because it makes their performance look better. And this may actually be the beginning of the

RIA PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS

Ironically, the fact that brokers’ purchase costs for clean shares will no longer be counted against mutual fund performance itself is kind of unique to broker-dealers. An RIA certainly gets his/her advisory fees counted directly against client performance. In particular, an RIA who wants to market a

I suspect that broker-dealers will use clean shares primarily to indicate the performance of their mutual funds. That’s not necessarily the same as performance of the account, because the account is net of the broker’s fee, but the mutual funds will not be. This means that mutual fund performance will be reported gross of broker compensation, but RIA performance will get reported net of AUM fees. Ironically, the fee drag pressure is felt more by RIAs, whereas in the past, it was felt by broker-dealers.

Perhaps the industry and consumers themselves will coalesce around some kind of reporting process that tracks advisor aggregate performance — whether broker-dealer or RIA — and it will look like net results net of all cost, and regardless of whether they’re applied at the advisor, broker-dealer or fund level. Maybe Morningstar itself will join the fray at some point.

This is frankly how performance should be tracked: net of all fees. But that’s not always practical with the available technology and reporting processes today, and the fiduciary rule and the rise of clean shares are certainly rearranging a lot of common industry practices.

Bottom line, we should recognize that with the rise of clean shares, there will be a fundamental shift in how brokers are getting compensated — even if it doesn’t change the total cost to consumers. As stated earlier, the consumer can pay a 1% commission trail or a 1% AUM fee; it’s still the same 1%. That said, it dramatically changes the expense ratio of the mutual fund — and therefore the performance of mutual funds themselves — which will no longer be saddling performance records with broker compensation.

That’s why in a few years we’re going to be noticing how actively managed mutual funds suddenly started doing better in Q3 of 2017. And it won’t be because the pendulum is swinging from passive to active, or because that’s when the Fed started accelerating rate increases, or whatever else happens from here. It will be because the fiduciary rule reconfigured how brokers get paid, reducing the need for 12B-1 fees and reducing the expense ratio of actively managed mutual funds, while improving their reported performance.

So what do you think? Are actively managed funds going to see a sudden increase in performance due to the changes in broker compensation? Will brokers start pointing to fund performance rather than account performance, since the former won’t include their fees? Please share your thoughts in the comments below.