I’m on record as being a skeptic when it comes to single premium immediate annuities.

Just two years ago, I

But looking for the answer to the financial advisor’s eternal question — How can we generate income for our clients? — and noting that nominal rates on bonds are at an all-time low with the iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF (

What initiated this second look was a column by one of my favorite financial experts and journalists, Jonathan Clements. On his Humble Dollar

Why?“I also want some income I’m guaranteed not to outlive,” Clements wrote. “Research suggests our ability to manage money deteriorates as we age. Research also suggests that retirees with predictable income tend to be happier.”

Great points. — longevity insurance and peace of mind are valuable. So, at age 63, I used myself to evaluate his theory. I went to

Looking at the chart, I decided that, for me, a $5 monthly reduction from the highest rate of $456 a month was worth the peace of mind to have a higher credit rating. I discussed this with two experts —

One big concern about buying a SPIA is that if a client dies shortly after purchasing, it may leave nothing for heirs. But this risk can be mitigated — somewhat — by buying a SPIA where an early death results in a payment.

For example, a minimum 10 years of payments from New York Life only slightly reduces the payment to $449 a month, which guarantees $53,880 during those 10 years — or a cash-back guaranteeing the full $100,000 back, though that reduced my monthly payment to $405. I decided to forgo these guarantees because the purpose of the SPIA is longevity insurance and paying to insure against both a short and long life seemed to defeat the purpose.

Simplicity a plus

While Blanchett and Pfau agree that delaying Social Security to get a much higher inflation-protected annuity is the single best option, both also said SPIAs were also good ways to supplement additional cash flows later in life.

“I like the simplicity of SPIAs with no bells and whistles,” said Blanchett, while Pfau said SPIAs were “a better alternative to bonds with steady payments calibrated to pending needs.” Both noted having additional guaranteed income allows one to spend a bit more safely from the rest of their portfolio.

My quote from New York Life stated that I would receive this 5.41% “income” for my lifetime, which is a heck of a lot more than any high-quality bonds or CDs. And only $65 of my $451 income would be taxable.

Of course, that’s because the IRS considers the $386 return of principal and doesn’t tax the whole payment until all $100,000 of principal is paid back. You cannot compare this 5.41% to the bond funds or CDs yielding 1.20% since those are pure income, rather than mostly return of principal.

Expected returns

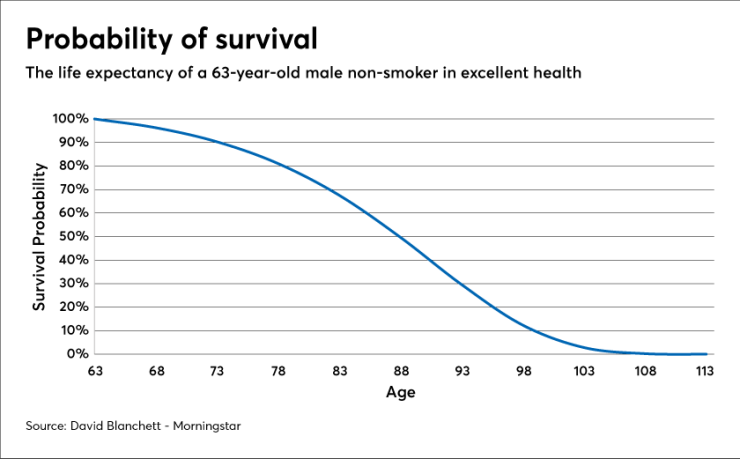

To determine the return I would get on this SPIA, I turned to estimated life expectancies. For a 63-year old male in excellent health, I have a median lifespan of 25 years though a life expectancy of just under 24 years, as calculated by David Blanchett on the

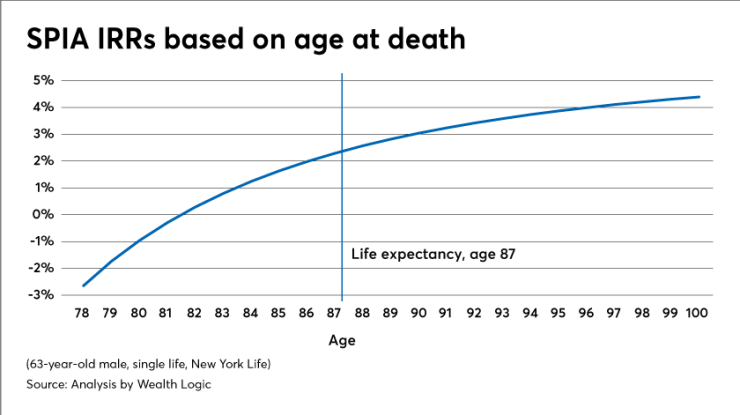

My expected return came out to be a 2.30% IRR, which compares favorably to a 20-year AAA corporate bond rate of 2.12%. While New York life is only AA+ plus, I take some comfort in the state guarantee should NY Life default.

On the other hand, the states would have to get the money from other insurance companies. In the event of a systemic failure, I agree with financial theorist and author William Bernstein that “during a generalized financial crisis the state guarantees would barely be a speed bump in slowing defaults.”

Blanchett and Pfau made the case using a Treasury bond as a benchmark. But only the U.S. government can print money, which gives a lower default probability, in my view. A 20-year Treasury was yielding only 1.13% when I conducted this experiment. Even using the AAA benchmark, however, it appears the SPIA delivers a slightly superior expected return along with longevity insurance and peace of mind.

The great unknown

Unlike Social Security, there are no longer inflation-adjusted annuities on the market. I suspect that’s because insurance company actuaries don’t want to take on the inflation risk, which is difficult and expensive to hedge against.

By my calculations, buying a fixed-rate annual COLA now actually increases the inflation risk and lowers the expected return. Pfau points out that it does, however, increase the longevity insurance. I compared the fixed annuity to one with a 2% annual COLA and the break-even was age 92, or five years past the life expectancy. Finally, a deferred income annuity (DIA) dramatically increases inflation risk.

So just how big is that inflation risk? No one knows. There are those who believe printing more money will lead to hyperinflation, though that hasn’t been the case in Japan. Over the next 30 years, for example, inflation averaging 2% annually (the Fed target) would reduce spending power by 45%. At 10% annual inflation, 94% of that spending power is gone. And if future inflation is at 3.1% (the historic CPIU between 1913 and 2019), 60% of spending power is lost.

There is now no way I know to safely protect against inflation. TIPS have negative real yields. Even a 30-year TIP produces a negative 0.33% annually, which guarantees loss of spending power.

Revised verdict

Revisiting SPIAs revealed some strong arguments for using them as part of a financial plan. On the other hand, one is trading longevity risk for inflation risk, taking on undiversified counterparty risk, since one cannot buy hundreds of SPIAs, and buying a bond-like portfolio when nominal yields are at an all-time low.

How good a bet are SPIAs?

| Pros | Cons |

| Longevity Insurance | Inflation risk |

| Peace of mind | Counterparty risk |

| Competitive expected return | Lack of diversification vs. bonds |

| Increases safe spend rate for remainder of portfolio | Long-term bond-like investment with historically low nominal yields |

Still, I was amazed at just how attractive the SPIA returns were compared to comparable bond investments. I won’t be buying for myself because I don’t need the cash flow at this time and waiting both increases the payment and decreases inflation risk.

But for clients withdrawing for their portfolios wanting some longevity insurance, this can make sense as part of the solution.

Finally, as financial planners, we must always be aware of our incentives and conflicts of interests. Fee-only advisors charging under the AUM model will likely reduce their incomes once the SPIA is purchased. But, as fiduciaries, we have an obligation to do what’s best for our clients.