When advisors try to broach the topic of long-term care with clients, they often hit a brick wall of denial. This makes it even more urgent that they do everything possible to break down resistance.

“What I hear most often is, ‘It won’t happen to me,’” says elder care attorney Robert Fleming. “And then it’s, ‘I’ll off myself if it does, or go on Medicaid if I can’t go through with it.’ You’ve got a lot of planning by denial going on out there.”

Clients are unlikely to bring the topic up on their own — unless they’ve seen someone close to them have to deal with declining health, says Kyle DePasquale, a wealth advisor for Sentinus in Oak Brook, Illinois.

“Ideally, it shouldn’t take something like that to get the ball rolling,” DePasquale says.

Besides the fact that death and illness are never easy subjects to introduce, the statistics are daunting. Clients who retire this year at age 65 will need to come up with about $280,000 to pay for health care and medical expenses through retirement, according to Fidelity. That’s up 75% from Fidelity’s first estimate of $160,000 in 2002.

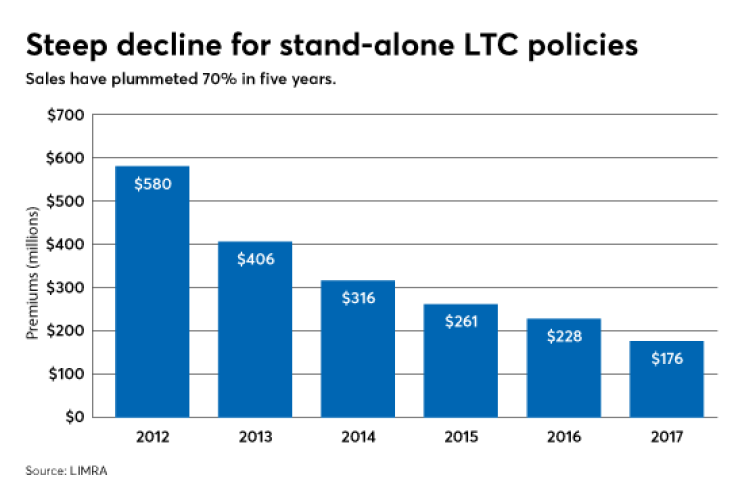

At the same time, the market for long-term care insurance has been in free fall. Premiums have skyrocketed, often doubling. Buyers are paying more but getting less coverage.

Even if a 60-year-old couple could afford annual premiums of around $3,500 for what the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance says might be a typical LTC policy for that age group, only a dozen or so companies still provide the coverage, The Wall Street Journal reported in a lengthy examination of the market.

A so-called silver tsunami will occur as a wave of baby boomers need long-term care.

Denials aside, the odds that a client turning 65 this year will need long-term care are around seven in 10, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. But less than 16% of adults have long-term insurance to pay for care, according to a study by the Life Insurance Marketing and Research Association.

Avoidance, the Planning Default

It’s no wonder avoidance is the planning default — which is exactly why advisors need to sit down with clients and have a talk about long-term care, experts say.

“It’s critical that financial advisors have a conversation about long-term care with clients, with documentation,” says New York-based elder care attorney Bernard Krooks.

Scroll through to learn about five core changes impacting retirees.

“Not only are you providing a necessary service for the client, you are protecting yourself from being sued by the client’s adult children, who, if things turn out badly, may say, ‘You should have talked to Mom and Dad.’ ”

The conversation should be about more than just money, says Jeannette Bajalia, president of Petros Estate & Retirement Planning in Jacksonville, Florida. “I talk to clients about well-being, about lifestyle and protection,” she explains.

“I’m also very brutal. I force couples to talk to each other about how they plan to deal with debilitating illness, lost income and whether they want to age in place or move to a facility.”

Advisors also need to have a discussion with clients about ”what extended long-term care could mean for their estate and the surviving spouse,” adds Jared Elson, managing partner at Regent Wealth Management in Morgan Hill, California.

“Annuity hybrids are giving the middle class an opportunity to cover themselves,” says Samantha Chow, senior analyst at Aite Group.

Eventually, of course, the conversation must turn to money. What are the options available, and how will the care be paid for?

The Self-Funding Option

Self-funding is a legitimate option for high-net-worth clients — especially ultrahigh-net-worth clients.

“The very best planning for long-term care is to amass great long-term wealth,” says Fleming, a partner at Fleming & Curti in Tucson, Arizona.

If clients are considering self-funding, advisors need to help them “run the math,” says Kim Garcia, principal of Diversified Trust in Greensboro, North Carolina. Imagine the worst-case scenario,” Garcia urges. “Figure on eight to 10 years of full-time care. How much will that cost and how will that number impact the portfolio?”

If clients place a high priority on having in-home care, using the income from a reverse mortgage is a viable self-funding option, Bajalia says.

“The very best planning for long-term care is to amass great long-term wealth.” says elder care attorney Robert Fleming.

“It’s part of a lifestyle choice,” she explains. “I use reverse mortgage as a vehicle that can be very cost-effective to bring care into the home. If staying at home is important to the client, I ask them if they think their son or daughter is going to change their diapers. Otherwise, how are they going to pay for the care they need?”

But DePasquale advises against self-funding.

“Clients are using their own money versus using leverage with insurance,” DePasquale says. “Why pay retail when you can get it at discount? You can self-insure your car, but who does that? Would you take liability and not collision? Even if people can afford to pay for long-term care themselves, why pay 100%?”

Another major caveat for most clients thinking about self-funding: They shouldn’t expect to leave much, if anything, to their heirs.

LTC Care and Hybrid Plans

Policies are expensive, premiums have been subject to eyebrow-raising increases, coverage has been shrinking and not very many companies remain in the market. Nonetheless, clients who can afford the price — and risks — of LTC insurance should consider it, Elson says.

“Traditional long-term care insurance certainly provides benefits if you need coverage,” he explains. “If you use it, it’s one of the best investments you ever made. Otherwise, it’s like car insurance if you never file a claim.”

Hybrid plans, meanwhile, are “where the long-term care market is going,” Elson says. These life insurance policies include a certain amount of long-term care coverage and feature premiums that are guaranteed not to rise.

They also offer lifetime benefits that are tax-free, as well as a death benefit for beneficiaries.

A major caveat for most clients thinking about self-funding long-term care: They shouldn’t expect to leave much, if anything, to their heirs.

“Hybrids can be the right answer for clients who are looking for life insurance and long-term care simultaneously,” Garcia says.

Rates for hybrids may be more favorable than buying separate policies, but she notes that prices “are very dependent upon the individual insured and the amount of coverage being sought.”

While Garcia likes the flexibility of hybrid plans, she warns that upfront premiums can be considerably higher — sometimes as much as 40% to 50% — than for a stand-alone long-term care policy.

Make sure clients get at least three quotes from different providers and carefully examine the separate costs of any riders that are attached to the policy, Garcia suggests.

In fact, a separate long-term care rider on a life insurance policy that accelerates the death benefit is another option for clients, DePasquale says. “If you need care at 80, for example, you can accelerate the death benefit so, when you need long-term care, you can get it early, sometimes at a discount,” she says.

A Caveat

There is a caveat, however. Payment of long-term care rider benefits as an acceleration of the death benefit reduces both the death benefit and cash surrender values of the policy.

The most attractive feature of hybrid plans, in Bajalia’s opinion, is the fixed premium.

“That’s my goal for clients,” she says. “With a fixed premium, clients can budget and protect their estate as well as their health.”

For asset-based long-term care insurance, clients deposit a sum of money with the insurance company instead of paying premiums.

The clients receive interest, and if they need care, the insurer pays benefits based on how much they deposited and how old they were when they purchased the policy — the earlier they start, the more benefits they get for their money.

If clients don’t use the policy, they should be able to get their money back, and if they die without needing long-term care, their heirs can still collect a death benefit.

The Annuity Plan

Some annuities are similar to asset-based long-term care life insurance policies. Clients make a lump-sum deposit that will pay interest, based on specific terms of the contract.

If long-term care is needed, a multiplier is applied to the cash deposited to pay out the expenses.

A rider can be added that provides for lifetime income payments that will be activated at some later point in time. An especially popular annuity option features an income rider commonly called a doubler.

A specified rate of income is guaranteed, contingent on how old the client is and when they begin taking distributions. But if long-term care is needed, that income is doubled for up to five years.

“These annuity hybrids are giving the middle class an opportunity to cover themselves,” says Samantha Chow, a senior analyst for Aite Group. “Long-term care insurance is so outrageously expensive that it’s not feasible for this market any longer,” she adds. “Fixed deferred annuities with health care provisions are affordable, serve more than one need and can be part of a holistic approach to financial planning.”

Indeed, advisors are generally enthusiastic about these products.

“They can help provide for nursing home care, in-home care, skilled nursing as well as be a source for lifetime income,” Elson says.

“Another nice thing is that they’re not life insurance — you don’t have to pass a medical exam,” he adds. “And they can be placed inside an IRA so clients don’t incur additional taxes.”

Bajalia, whose books include Planning a Purposeful Life, says she likes the hybrid annuities so much that she owns two herself.

“It’s a beautiful way to fund some long-term care protection,” she says. “There are multiple benefits, including an income stream.”

She especially likes fixed deferred annuities with index features and long-term care provisions that continue the doubler payments even if the cash value of the account zeroes out.

Caution: Examine Policies

But Bajalia cautions that advisors must insist clients examine the policies carefully. Some annuities, she warns, may not pay out the doubler rider if accessed too early and the account value goes to zero.

Another caveat comes from Fleming, the elder care attorney.

“Annuities sold in advance of institutionalization are almost always a bad idea,” he says. “There’s a potential income tax hit if the annuity has to be cashed in. And [the decision on] how to use the annuity is being made at a time when someone’s mental capacity may be diminished.”

Care Communities

A combination of independent living, assisted living and a nursing home with on-site medical care and an emphasis on community, Continuous Care Retirement Communities are growing in number and popularity.

The catch is the cost: The average entrance fee is around $250,000, according to industry estimates.

And that’s before monthly fees, which can range from $1,500 to $10,700, depending on such factors as the terms of the contract, type of housing, size of the facility and services provided, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

For those who can afford these communities, the emphasis placed on socialization is a major benefit, especially as people live longer, Bajalia says.

But she cautions clients to study whether the facility has a history of rate increases and whether the contract protects an estate by reimbursing money if the client dies unexpectedly.

When making a visit, clients should ask people there what their experience has been and “understand the white space between the contract language,” Bajalia counsels.

While a care community can be a good option, Garcia adds, they don’t eliminate all costs and “only last as long as the client’s money does.”

Outside Help

Issues involving estate protection, taxes, trusts, charitable gifting, heirs and a surviving spouse are integral to long-term care planning. In this capacity, elder law attorneys can be an invaluable resource for advisors.

“It’s a relatively new and still evolving field with laws that vary state by state,” says Fleming, a former head of the National Elder Law Foundation. “We see more attorneys working very closely with advisors all over the country.” Regent Wealth Management refers clients to elder care attorneys on a regular basis, Elson says. “It depends on the estate, and what they’re trying to accomplish.”

“If you’re dealing with Medicaid and want to protect assets, it’s vital to have an elder care attorney,” he adds. “If there’s not as many assets involved, it’s not as important to work with them.”

Paradoxically, it’s middle-class clients who have the most to lose if long-term care is needed, Elson says.

“The folks in the middle are the ones with the real exposure,” he notes. “The change in lifestyle can be dramatic, especially for the surviving spouse. They can use the most help.”