Often, despite nostalgia, memory lanes don’t lead us back to better places, just the same wrong turns we’ve made before. That would be the case with Wall Street’s latest proposal to improve the stock market. The SEC should see it for the unsensible stroll it is.

On Monday, a group of the biggest banks and brokerage firms

The impetus for the new exchange seems to be fees. For the past few years, there has been a growing chorus of complaints from brokers that the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq essentially hold a duopoly that has allowed them to drive up fees, particularly on data. But what’s also driving the Members Exchange is growing nostalgia for a not-so-long-ago era when the NYSE, the Nasdaq and other exchanges were owned by their members, rather than for-profit publicly traded entities. In a statement the nine founders of the new exchange said they are “seeking to increase competition, improve operational transparency, further reduce fixed costs and simplify the execution of equity trading in the U.S.”

The NYSE and Nasdaq’s profit motives have indeed produced some ill effects.

The good times in munis aren’t likely to last as the Fed’s push to boost interest rates will hamper future results, an expert says.

But the era when the brokers owned the exchanges was worse. Infighting among the firms, which wanted to maintain their trading profits, left the NYSE unable to innovate and prone to scandal. Trading times were 10 times as long as at rivals. The NYSE’s floor brokers were accused in the early 2000s of lining their pockets with the help of large firms at the expense of small investors. The Nasdaq didn’t have as many problems, but it, too, used its broker-owned position to create a central order book structure that limited competition by outside trading firms.

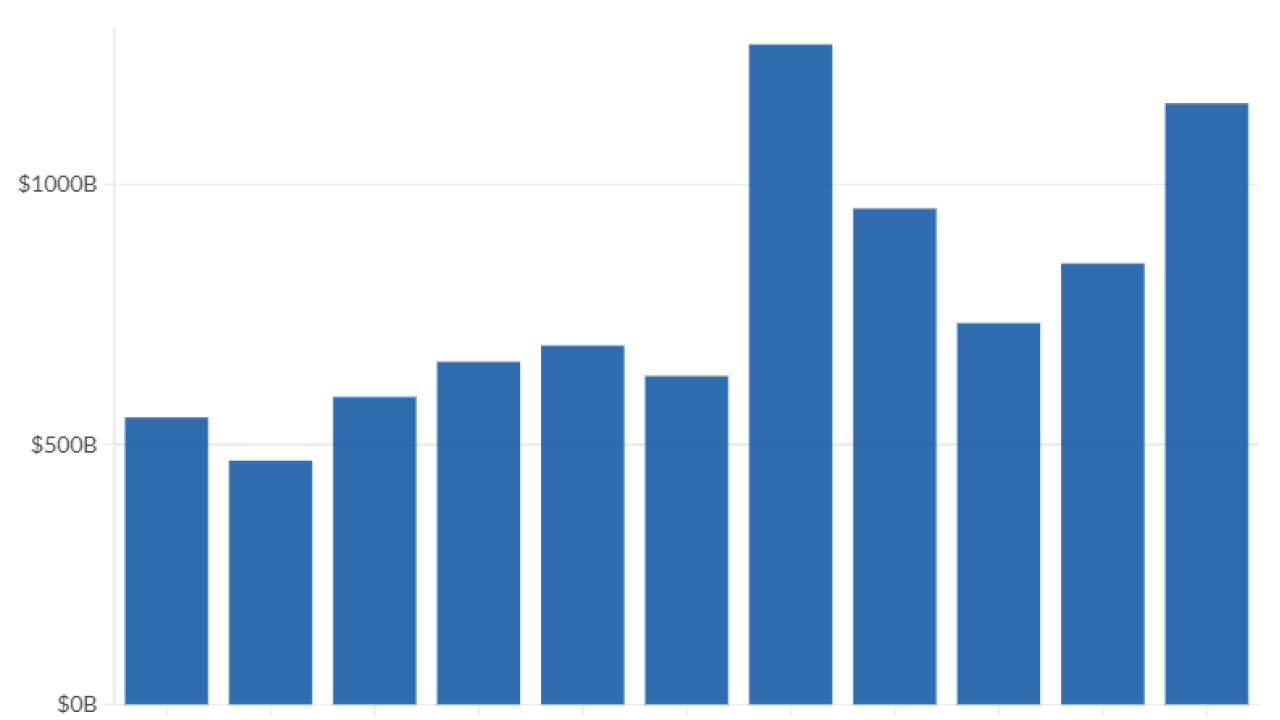

It’s true that the exchanges, even by their own accounts, have rapidly increased data fees over the past few years. They say that’s justified because they have been hit by lower costs elsewhere. But the problem of data fees was created not by monopolies but by regulation that requires brokers to obtain the best prices for their clients. Even if there was an exchange with just 10% of the volume of trading, it could still force brokers to pay what it wanted. Best execution requires brokers buy data from every meaningful exchange. That’s the only way they can be sure they are getting the best price for their clients.

It’s the SEC’s job to step in and fix the unintended costs of well-intended regulation, which is what Brett Redfearn, the head the regulator’s division of markets and trading, appears to be doing. He’s proposed a trial to test whether the rebates paid by exchanges to attract trades create conflicts and hidden fees. He’s also sought out input on whether the SEC should regulate data fees and how. Redfearn should get the time he needs to try to find balance for Wall Street’s future. By allowing Wall Street to re-create member-owned exchanges, the SEC won’t increase competition, as the brokers claim, but just introduce an old force for the monopolization of stock trading and a step backward for average investors.